In his confirmation hearing as Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. argued that U.S. health-care spending represents a “20 percent tax on the entire economy.” Rather than engage in a “divisive debate about who pays,” he suggested the nation ask, “Why are health-care costs so high in the first place?”

Kennedy offered his own answer: “chronic disease,” to which “90 percent of health-care spending” is devoted. He specifically pointed to rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and cancer, as well as “autoimmune diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, Alzheimer’s, asthma, addiction,” and more besides. He blames poor diets and environmental toxins for the rise in chronic disease rates.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In truth, the growing burden of chronic disease owes mostly to increased affliction by the diseases of old age. In 2019, the year before Covid hit, U.S. life expectancy was 78.8—a hair’s breadth below 2014’s all-time high of 78.9, and well up from 47.3 in 1900. This owes much to progress in medical science and increased spending on health care; but it also reflects improvements in urban sanitation, widespread vaccination, and reduced consumption of alcohol and tobacco.

Obesity remains a problem. The U.S. obesity rate is twice the average for developed countries, which accounts for America’s higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and stroke. It also explains America’s higher death rate from Covid-19.

Though Americans’ diets are more varied and fresh than a half-century ago, they also consume more sugars, soda, and processed foods. Kennedy blames these, along with additives and dyes, for much of the nation’s ill health, telling Congress that “we shouldn’t be giving 60% of the kids in school processed food that is making them sick.”

Americans have always eaten a lot. Nineteenth-century Americans consumed over 1,000 calories more per day than the English and French. But it’s hard to force Americans to change their diets, as New York mayor Michael Bloomberg discovered when he attempted to ban the sale of supersized sodas. “I don’t want to take food away from anybody,” Kennedy assured Congress. “If you like a McDonald’s cheeseburger or a Diet Coke, which my boss loves, you should be able to get them.”

As Secretary of Health and Human Services, Kennedy will lack the power to alter meaningfully Americans’ diets. Congressional agriculture committees view farm subsidies, like those supporting high-fructose corn syrup, as their prized possessions. They also control the food stamp and school breakfast programs, the latter of which has been shown to increase obesity. When Congress has delegated authority over dietary guidelines to the executive branch, it has entrusted them to the Secretary of Agriculture. In President Trump’s first term, that led to an effort to alter food stamp program nutrition requirements so that they could be satisfied by canned spray cheese and beef jerky.

For the bulk of his career, RFK was an environmental activist committed to clearing rivers of chemical pollutants. In his confirmation hearing, he argued that “human health and environmental injuries are intertwined,” noting that the “same chemicals that kill fish make people sick also.” He can do little about this at HHS, as the regulation of pesticides is entrusted to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Kennedy’s environmentalism seems to have left him with a prejudice that nature inherently means humans well, and that unexplained disease is likely the product of artificial toxins. He has speculated that Wi-Fi causes cancer, that school shootings are caused by antidepressants, that chemicals in the water are responsible for gender identity disorders, and that vaccines cause autism.

To be sure, overmedication is a real problem. America has seen a proliferation of costly drugs with only slight therapeutic benefits, which may unleash a prescription cascade to deal with side effects. RFK Jr.’s skepticism of “unnatural” pharma may therefore be helpful if it leads him to resist attempts to weaken prior-authorization oversight on utilization.

Elsewhere, though, his instincts lead him astray. Kennedy told Congress, “I was raised in a time when we did not have a chronic disease epidemic,” and suggested that, since his uncle’s presidency, the proportion of children with chronic illnesses had surged from 2 percent to 66 percent.

These seemingly alarming statistics owe much to greatly broadened definitions and increases in the diagnosis of food allergies and behavioral health conditions that no one was tracking when JFK was in the White House. In reality, child health has improved dramatically, and the rate of mortality per 100,000 children has declined from 68.6 in 1962 to 24.9 in 2018.

RFK also claimed, “We spent zero on chronic disease during the Kennedy administration. Today we spend $4.3 trillion a year.” The first statistic is clearly false (cancer and heart disease existed in the early 1960s); and much of the second can be explained by increased longevity.

Chronic disease is often a price of medical success and of aging. Improved treatment has turned the most serious medical conditions, such as heart disease, into things that people live with for years instead of dying quickly—and cheaply. Consider: age-adjusted deaths from heart disease fell by 67 percent from 1970 to 2018, while those from strokes declined by 75 percent. Deaths from prostate, colorectal, lung, and stomach cancers have all been halved since 1990.

The more medicine advances, the more work it has to do. Tissues, glands, and bones degenerate over time, and the effectiveness of medical care diminishes with age. The longer medical progress helps people live into old age, the more drawn out the period of bodily decline will be, with intractable and hard-to-cure conditions figuring more prominently.

This burden of chronic disease falls largely on the elderly. Relative to adults aged 35 to 50, those over 80 are nine times more likely to have cancer, ten times more likely to have diabetes, 18 times more likely to have COPD, and 47 times more likely to have a stroke. Whereas Alzheimer’s disease afflicts only 2 percent of those aged 65 to 74, it touches 43 percent of those 85 and older.

Environmental toxins and unhealthy lifestyles can certainly precipitate bodily decay, but they are they are not the main reason for the rising cost of chronic illness. Increased spending on the treatment of chronic medical conditions is the product of a wealthier society with greater longevity. It’s an unpleasant problem, but it beats the alternative.

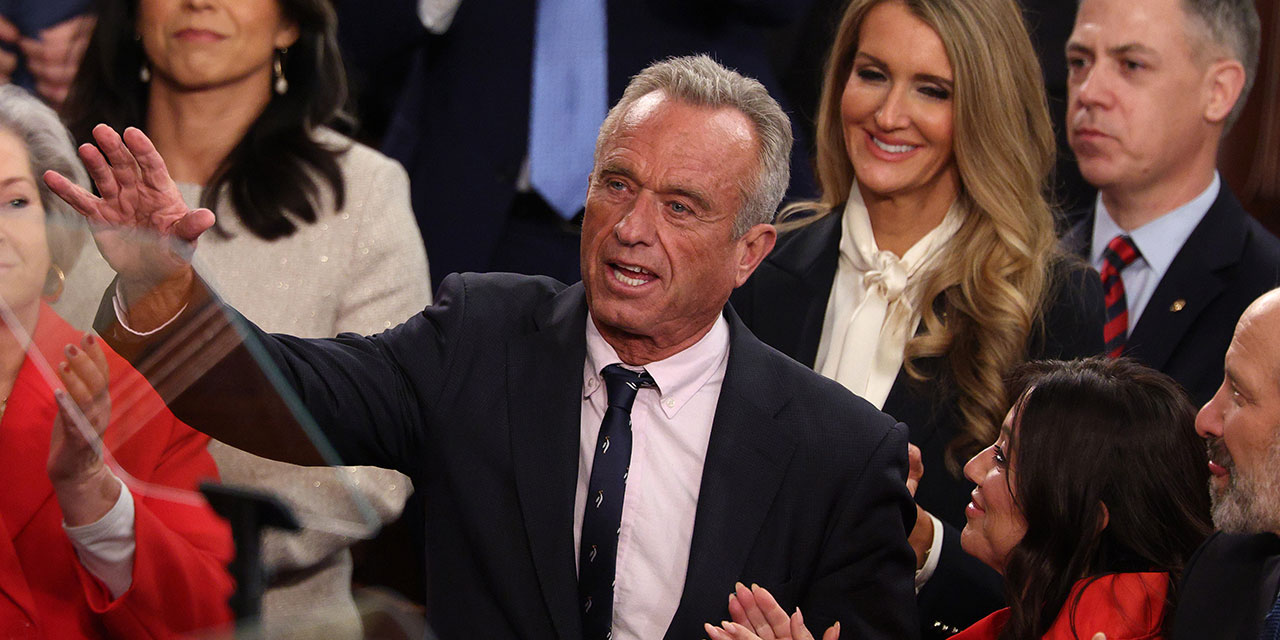

Photo by Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images

Source link