It’s not often that a mistake improves a performance. Earlier this month, when Los Angeles’s long-established early-music ensemble, Musica Angelica, performed Henry Purcell’s Fantasia Upon One Note, a hesitation by the violist when changing bows became one such moment. The Fantasia is, in fact, a fancy on one note. Purcell sustains a middle C throughout, and the violist’s hesitation on this note revealed how strange and unnatural this conceit is. Purcell forces the violist to play this single pitch for several minutes while the others weave lines around him. The slight lapse in bowing broke Purcell’s spell.

Of course, strangeness is not sufficient for an artwork to be considered great. “New” and “experimental” can be wonderful things, but what is new is sometimes only a novelty. Experiments fail. What makes it more than a whim in Purcell’s Fantasia is how musical it sounds, how much variety Purcell gives us despite constraining himself to a drone. The Fantasia becomes a model of invention. The limitation makes Purcell more creative rather than less so. For some composers, the constant pitch would be a disaster or, worse, boring. For Purcell, it becomes another invitation to the canon.

His originality is also apparent in another work on Musica Angelica’s program, Chacony, for two violins, viola, and basso continuo. Here, he uses a repeated bass and harmonies over which the ensemble plays variations. A common form in the seventeenth century, the chaconne originated as a wild dance from the New World. It had an irresistible pull for composers wanting to display their “divisions,” their development of simple musical materials. As in the Fantasia, Purcell thrives in its barren climate. The restrictions of the form, like its repeated bass line, seem to free him from any restraint in harmony or counterpoint. He will suddenly change mode, with an unexpected shadow falling over the harmony, or he’ll cross dissonant pitches, so the composition becomes a painting with a single vivid point of light. The strangeness in this Chacony is Purcell’s color-changing lines.

The music of Heinrich Biber (1644–1704), which introduced the concert, also has its own strangeness. In the program, we hear his characteristic “fantastic style”: his quick-changing manner and dramatic settings. His music has theatrical clarity. In Sonata No. 1 in Ba minor, from Fidicinium Sacro-Profanum, he begins with a moment of fast, precise, and intense bow strokes before subsiding into an ecclesiastical adagio. But even this slow movement wanders through unusual harmony as it descends. After this gentle introspection, Biber abruptly gives us an allegro. These quick contrasts are exhilarating with musicians as skilled as Musica Angelica’s, and it is a startling way to begin a program.

The ensemble and its director, Ilia Korol, kept the concert’s first half under tight control. Korol, a violinist, brought a measured expressiveness to this part of the program, which focused on works for strings and continuo by Biber and Purcell. The only faults in the ensemble were brief lapses into a muted, overly connected romanticism. Katherine Heater, who played organ and harpsichord, chose to perform most of her parts on the organ, which vanished into Musica Angelica’s texture. It gave the continuo mass but left the ensemble sounding, at times, more like a viol consort. Her choice suggested more of the sacred side of Fidicinium Sacro-Profanum rather than anything profane. It was a valid decision, but one of the era’s glories is the harpsichord rustling behind viols and violins. This music works best not in voluptuous blends of sound like in Brahms but in astringent contrasts: loud and soft, short and long, bright and dark, recorder and theorbo, viol and harpsichord. Still, it was attractive playing.

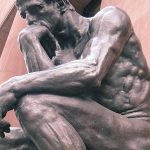

Musica Angelica dedicated the concert’s second half to the composer Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (ca. 1620–80). He shares something of Biber’s “fantastic” sensibility, though he was from an earlier generation of Austrian composers. And like Biber, he was a virtuoso on the violin, which shows in his energetic style. The ensemble abandoned their former restraint, stamped their feet, and struck their instruments with the wood of their bows. The titles were also playful: Balletto di filosofi (a ballet of philosophers) and Balletto di capitani (ballet of captains). Di spoglia di papagi was three minutes of light entertainment in which a saltarelloleapt, and it was as if a Scaramuccia—a clown from commedia dell’arte—strutted through syncopated lines.

They ended with Schmelzer’s Serenata con altre arie in five movements, some broken into contrasting sections. Each movement passed too quickly for distraction. For example, the second, “Erlicino,” likely refers to another commedia dell’arte character, Arlecchino, a comic figure but also something of a skirt-chaser. You could hear this in Musica Angelica’s performance—the first section was full of quick, slight, somewhat sly runs. The second, a slow Adagio, likely depicted Arlecchino mooning over the mischievous servant Colombina. It ended with a comic Allegro—the marking denotes a quick tempo, but the word translates from Italian as “cheerful.” All three sections didn’t take more than a few minutes.

Music Angelica called their concert “The Garden of Forking Paths.” In the program notes, there is a description of a unicursal labyrinth in which a subject passes to and from the center without knowing it. It’s a telling analogy for many concerts. Sometimes, when we approach an older piece, its strangeness has long been obscured by common practice. We pass over what once made it great. Sometimes, a mistake is all we need to realize we’re at its center again.