The United States must prevent a Turkish-Sunni bloc from replacing the Iranian-Shia bloc as the regional troublemaker.

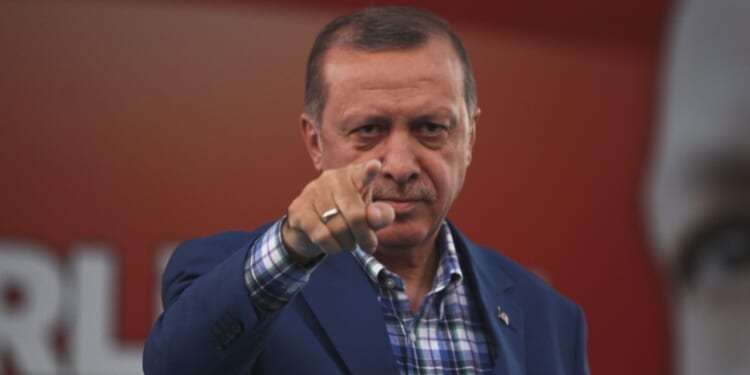

Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu could only offer a tense smile in the Oval Office on April 7 when President Donald Trump expressed his admiration for Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan and congratulated Turkey on taking over Syria. Nor did Netanyahu look particularly reassured when Trump claimed that he could “solve” any problem between Israel and Turkey.

To further complicate matters, sources suggest Trump may meet with Ahmad al-Sharaa, the newly appointed Syrian president and former leader of Al Qaeda’s Syrian branch. This move will certainly raise anxieties in Israel and across the region. There is wide speculation that Turkey has secretly been supporting al-Sharaa and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). This group has ruled Syria since the fall of Bashar al-Assad in December 2024.

Perhaps Trump hopes Turkey’s influence in Syria could support the U.S. counterterrorism effort and contain Iranian influence in the region. But these hopes are overly optimistic. In all likelihood, Assad’s fall from power—and the emergence of al-Sharaa in his place—will simply replace one problem with another.

To be clear, the fall of the Assad regime is a positive development for the interests of the Middle East and the United States. It has significantly weakened Iran and its “Axis of Resistance,” which seeks to expel U.S. forces from the Middle East and destroy the state of Israel. In its place, however, the United States now faces the rise of a Turkish-backed Sunni axis that likely shares the same goals. Recall that it was Arab Sunni militaries and militias, not Shia ones, that were at the forefront of armed conflict against Israel from the 1940s until 1979 when Iran emerged as Israel’s foremost adversary.

With Iran’s regional influence quickly fading, the traditional order appears to be returning. Erdoğan, who has ties to the Muslim Brotherhood and has espoused Islamist views, is inciting renewed Sunni aggression against Israel at a time when Sunni Arab states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE are seeking to normalize relations with the Jewish state. In a March 31 speech, Erdoğan prayed for Hamas and Israel’s destruction. Shielded by a Turkish security umbrella in Syria, HTS can now pursue more radical objectives that threaten both regional stability and Israeli security.

Israel has not stood by idly as Turkey attempts to make inroads into Syria. Since the fall of Bashar al-Assad, it has launched airstrikes and even conducted ground operations in Syria to deny Turkey access to Syrian military installations like the T-4 airbase in Tadmor. It has communicated to Ankara that it considers the establishment of a Turkish military base in Syria a red line.

Israel is also building ties with the Syrian Druze community, a religious minority in southern Syria that would be justifiably alarmed by a Sunni Islamist regime in Damascus.

Israeli and Turkish representatives recently met in Azerbaijan, a country that has maintained close relations with both states, to ease escalating tensions and deconflict their military operations in Syria. However, only the United States has the power and influence to mediate between two allies that seem poised for rivalry and potential conflict.

While the United States’ desire to avoid triggering an escalation with a NATO ally is understandable, this should not translate into a policy of appeasement toward Turkey and its emerging proxy in Syria. Washington has several tools at its disposal to ensure a balanced power structure in Damascus, deter a resurgence of Sunni radicalism among Arab states, and contain Turkey’s attempts to expand its reach across the Middle East.

First, the United States must not lift the sanctions it currently has in place against HTS. Any easing of sanctions on the group—which has professed to have disbanded but whose leaders still dominate the new Syrian government—should be clearly conditioned on meaningful reforms. Crucially, the first of these reforms must be the removal of all radical and jihadist elements still active within the new HTS-led Syrian government.

Al-Sharaa has signaled that he is no longer the young fanatic who once joined terrorist groups and is now advocating for the modernization, liberation, and democratization of Syria. Washington must hold him to these promises and withhold formal recognition of the new Syrian government until he follows through.

Second, the United States should reconsider its stance toward Russia’s remaining military presence in Syria. Most of Russia’s military infrastructure across the country has already been dismantled; what remains is a limited presence at the Khmeimim airbase. Although the United States and Russia are in conflict elsewhere in the world, neither would be well-served by a fanatical government in Syria intent on destroying Israel.

Indeed, it is notable that Jerusalem reportedly encouraged Washington not to pressure the Assad regime to expel Russian forces in the past, viewing their presence as a check on both Iran and Sunni radicals. Given the historic rivalry between Russia and Turkey in the region, particularly in Syria, giving Russia a stake in Syria could serve as a counterbalance to Turkey.

Third, the United States must increase its support for the Lebanese national government and the Jordanian monarchy. There is a growing risk that Turkish-backed elements and radical Sunni groups operating in Syria may seek to destabilize these neighboring states. Such unrest could jeopardize key American allies and heighten the security threat to Israel.

This problem is particularly acute in Lebanon, where the collapse of Hezbollah’s power has led to major steps forward for stability and peace. The United States should do all that it can to preserve this.

Fourth, the United States should follow Israel’s example and conduct outreach to Syria’s minority groups—the nation’s Druze, Kurds, Alawites, and Christians. Strengthening these communities can enhance their security and provide America with critical leverage against HTS or other radical elements.

Independent relationships with these minorities—ranging from political to military support—can serve U.S. strategic interests by maintaining balance and preventing extremists from once again using Syria to destabilize the Middle East. The United States should also tie sanctions relief to the diversification of Syria’s political leadership, ensuring that minorities and non-dominant groups are given a real stake in governance.

Turkey is no substitute for Iran in the Middle East. In its unreformed form, HTS will likewise be no better for Syria’s future than Assad was. In short, Sunni radicalism cannot be a replacement for Shia radicalism. The United States must ensure the Turkish military does not fill the void left by the Russian or Syrian militaries. It also must pressure HTS to renounce any connections to terrorism and maintain a demilitarized border with Israel. Syria must not become the safe haven and starting point for another revisionist axis.

Arman Mahmoudian is a research fellow at the USF Global and National Security Institute. He is also an adjunct professor at the University of South Florida’s Judy Genshaft Honors College, teaching courses on Russia, the Middle East, and International Security Follow him on LinkedIn and X @MahmoudianArman.

Jeff Rogg is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of South Florida’s Global and National Security Institute. He also sits on the boards of the International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence and the Society for Intelligence History. His book, The Spy and the State: The History of American Intelligence is forthcoming with Oxford University Press in May 2025. Follow him on X: @TheSpyTheState.

The views expressed in this article by both authors are their own.

Image: Kafeinkolik / Shutterstock.com.