John Thayer (1755-1815) was a wealthy Protestant born into the long history of New England Protestantism, especially Puritanism, which had convinced many of the important role America was to play in the fulfillment of God’s historical plan for Christianity. They believed that the religious freedom afforded to Americans by Protestant Christianity had been part of God’s great design in ushering in political freedom to the world.

John Thayer, a descendent of Puritans, grew up in Boston and attended Yale College, where he learned the political and religious beliefs that erupted into the American War for Independence. After graduating, prepared to pursue his life as a Congregational minister, the war impeded his plans, and he opted to pursue his goals by becoming a chaplain. As the war drew to a close, Thayer, who like many Americans experienced the unmitigated violence of war, began to question some of his most cherished beliefs; he decided to travel to explore the culture, languages, and ideas of Europe, especially in France and eventually leading him to Rome.

Thayer had been raised to believe that Roman Catholics were veritable servants of the Anti-Christ, which many Protestants believed the pope to be. Further, many believed that the missionaries who had brought Catholicism to America, especially the Jesuits, were evil, conniving people who willingly taught falsehoods to ensure their own power and influence. In converting the Native Americans and ingratiating themselves among these superstitious people, the Jesuits had ensured that they could use them to attack Protestant Christians in New England—hence the horrors of King William’s, Queen Anne’s, Dummer’s, King George’s, and the French-Indian wars.

To Thayer’s utter surprise, when he toured France and Italy and engaged Catholics in conversation—even Jesuits!—he found himself welcomed, respected, and at home. In Rome, against his previous intentions, he began to fall under the “spell” of Catholicism: the liturgy, the saints, the Virgin, the priests. “Thanks to that admirable Providence,” he later recalled, “which made all conduce to my good; as the desire of travelling had led me to the centre of light, without my knowledge, so the desire of instructing myself, brought me to the knowledge of the truth without my intention.” Providence overrode his plans. He attended the Seminary of St. Sulpice in Paris, where he was ordained in 1789.

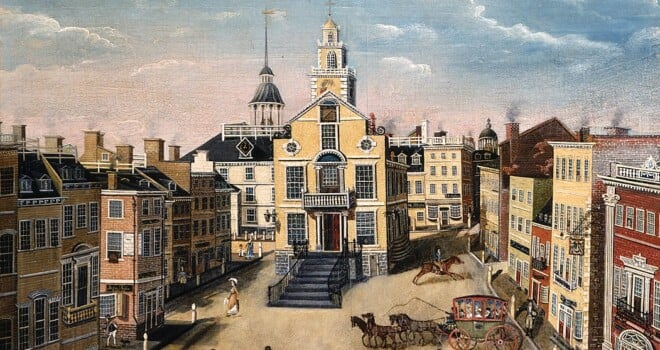

When the French Revolution broke out, he fled France and returned to Boston, which was still a Protestant stronghold. The small number of Catholics in the city were mostly French-speaking immigrants and a few Irish, and neither saw eye to eye. The French were suspicious of a convert American priest, though the Irish were more tolerant of Father Thayer. The first American bishop, John Carroll, consecrated Father Thayer—the first native New Englander so honored—and gave him permission to organize a church and begin spreading the Good News throughout the greater Boston area.

Father Thayer had an unexpected ally, Samuel Breck, a Boston native who as a teenager was sent by his parents to study in Paris, where he came to know Thayer at the Seminary of St. Sulpice. Breck was also a convert to Catholicism, and the two men had formed a friendship; however, when Breck returned to Boston, he lost his convictions and returned to his Protestant beliefs. Learning that Father Thayer was in town and that he sought to start a new Catholic parish, Breck, who believed that Bostonians after the war were less biased toward Catholics, helped Thayer find an old building on School Street that, with some renovation and furnishings, they turned into a parish.

“At length,” Breck recalled many years later, “everything was prepared to solemnize the first public Mass that was ever said in Boston—in a town where thirteen years before the Pope and the Devil were annually promenaded through the streets and finally burned together.”

Samuel Breck was not entirely correct in saying that bygones were bygones between the Catholics and Protestants. The Congregational ministers of Boston were not happy about an apostate Protestant minister turned Catholic priest opening up a parish in the heart of the “City upon a Hill.”

In example of this, the Protestant clergyman and historian Jeremy Belknap had written a history of colonial America in which he described the Wars for Empire between the English and the French, accusing the French of converting the Algonquian tribes of northern New England not only to Catholicism, but to hatred for Protestants as well.

Thayer, responding to the book, reprimanded Belknap for not presenting both sides of the story—that Protestants had been just as violent and warlike as their Native American counterparts, and that French priests did them a service not only by converting them to the true Faith but also by helping them defend their homeland against aggressive Protestant militia forces. Thayer accused Belknap and other New England Protestants of bias and name-calling, taunting Catholics as superstitious idol-worshippers.

Thayer tried his best to bring the Catholic interpretation of the Great Commission to New Englanders in general and Bostonians in particular, but without much success. He grew frustrated in the attempt and wrote Bishop Carroll requesting a new assignment as a missionary in the trans-Appalachian West. Carroll agreed, assigning Father Thayer to Kentucky, where there had been an active Catholic missionary presence for many years.

Thayer arrived in 1799 and immediately came into conflict with Father Stephen Badin. Previously, Father Badin had requested Thayer’s reassignment and looked forward to working with him, thanks to his memoir, The Conversion of the Reverend John Thayer, formerly a Protestant Minister of Boston, Written by Himself. But then came the controversy.

Badin and the other Catholic priests in Kentucky relied on slave labor, and Thayer was an avowed abolitionist. Catholics such as Father Badin argued that slaves were children of God deserving baptism and the sacraments, but that their inferiority to whites meant that enslavement was “what was best for their own needs.” Thayer was at first outraged and refused to use two slaves given to him by parishioners. However, in time, he was convinced that God was calling him to build a new Ursuline Convent in Kentucky, which he could not do without slave labor. It’s clear in retrospect that Thayer was torn by this decision, which he no doubt believed was using a necessary evil, slavery, to achieve a good, the convent. But eventually the pressure and guilt from the decision drove him from Kentucky—and from America entirely.

Thayer left to become a parish priest in Limerick, Ireland. There he met James Ryan, his daughters Margaret, Anne, Mary, and Catherine, and their cousin Catherine O’Connell Molineaux. Thayer, thinking about his homeland and wishing still to build an Ursuline convent, believed that one way to do it was to help these young women join the Ursuline convent in Quebec. He wrote his friend Father Anthony Matignon in Boston to help the Ryans and their cousin. The young women departed Ireland and traveled to America, where Father Matignon welcomed them and helped them to travel to the Ursuline convent at Trois Rivières in Canada, where they entered their novitiate.

Meanwhile, Father Thayer became ill and died. He had inherited wealth and wished to leave behind a financial legacy with instructions to Father Matignon to invest the money for the purpose of eventually building an Ursuline convent in Boston. Father Matignon’s investment yielded good returns at the same time that the Ryan women became Ursuline nuns. They held onto their desire, inspired by Father Thayer, to go to Boston to organize a convent. The Ryan sisters arrived in Boston in 1820, opened the convent in nearby Charlestown, and began working with the poor.

In time, as renewed anti-Catholicism swept New England, the convent in Charlestown became notorious as a place where, Protestants believed, Ursulines “groomed young women for diabolical purposes.” The anti-Catholic bigotry that John Thayer had been taught as a child, and that he experienced when he returned to Boston as a priest, rained down in dreadful fire in 1834 when the Mount St. Benedict Convent was attacked and burned down by an angry mob of Protestants, becoming a symbol of the destructive hatred that Christians—and all humans—fall prey to.

Father John Thayer had tried. Although his efforts in Boston at the time appeared feeble and unsuccessful, and although the Ursuline convent burned, never to rise again, the memory of the love and charity underlying these attempts would long outlast the brief moments of apparent failure. God’s story is greater than ours, and we’ll only see His great plan on the other side of the veil.

Image from Wikimedia Commons