American policing has faced significant challenges over the last decade, with major upticks in homicide and shootings during the pandemic, legislation restricting policing practices, and a “defund the police” movement that gained momentum in 2020 before declining in popularity. Criticisms of the police profession have also included attempts to rewrite the origin story of American law enforcement. One popular but false narrative holds that modern policing in the United States emerged from nineteenth-century slave patrols—a potent “original sin” argument, suggesting that the police are permanently stained by the legacy of American slavery. In truth, any connection between policing and slavery is tenuous, at best.

The basic model of American policing was inspired by London’s Metropolitan Police, established in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel to manage mob behavior and public disorder. In 1837, a young Abraham Lincoln warned of the “increasing disregard for law which pervades the country” and the “growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions in lieu of the sober judgment of courts,” a sentiment echoed by the wave of violent and ethnic mob riots sweeping American cities during that decade. In the 1840s and 1850s, cities such as Baltimore, Boston, Philadelphia, and New York created modern police forces to address a surge in ethnic mob violence. These urban riots often involved attacks by native-born Protestant groups on Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany, or by Irish and other ethnic mobs targeting free blacks. Policymakers of the era looked to London’s approach as a solution to their pressing public-order challenges.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Municipal governments in Southern slaveholding states, on the other hand, did not develop modern police forces until after the Civil War. Before then, they relied on paramilitary volunteers—the infamous slave patrols—to suppress potential slave revolts and maintain the slavery system. The only major metropolis in the South during the 1840s was New Orleans, where policing followed the French military model of the gendarmerie rather than the civilian-focused London Metropolitan Police. New Orleans’s gendarmerie lived in barracks and marched with rifles and swords. New Orleans transitioned from this gendarmerie system to a modern police force in response to rapid urbanization. In Northern cities following the London model, by contrast, police were initially unarmed and worked on patrol to keep order. As historian Eric Monkkonen observed, the stark difference between the development of police forces in the North and the South during the antebellum period underscores a critical point: “An unfree society cannot support a modern police system.”

Yet the movement to rewrite the history of policing goes further than the dubious connection to slave patrols. It has trained its sights on August Vollmer (1876–1955), who served as Berkeley, California’s first police chief, from 1909 to 1932, including a one-year leave of absence to lead the Los Angeles Police Department in 1923. Vollmer became the leading advocate for professionalization of policing. Today’s revisionists charge him with pioneering a modern policing model that borrowed military tools to reinforce unjust racial hierarchies.

As is often the case with bad revisionist history, the narrative largely stems from a single scholarly article that credulous journalists have popularized. “The Imperial Origins of American Policing: Militarization and Imperial Feedback in the Early 20th Century,” by the University of Chicago’s Julian Go, has received dozens of citations since its 2020 publication in the American Journal of Sociology. Go’s paper purports to find, through a study of Vollmer’s career, the essentially imperialist character of twentieth-century police reforms—and to “connect domestic race relations with colonial relations” overseen by the military. Go’s campaign to sully Vollmer’s legacy has proved influential among academic criminologists, a growing number of whom want to cancel the American Society of Criminology’s August Vollmer Award—never mind that Vollmer founded the ASC in his living room in 1941 with several of his former protégés. A July 2020 New Yorker story by Jill Lepore relied heavily on the Go article to lament Vollmer’s legacy as “refashion[ing] American police into an American military.” Written at the apex of public antipolice sentiment, Lepore’s article begins with the slavery claim but traces the defects of modern policing to Vollmer’s work.

These views conveniently align with the goals of today’s antipolice activists. Academics seeking to link the professional model of policing to militarization and colonialism must cast Vollmer—the principal architect of modern American policing—as a villain. Recovering Vollmer’s true legacy is a necessary task for those who want to see genuinely effective policing in the United States.

Born in 1876 to German immigrants, Vollmer spent a childhood between New Orleans and Berkeley before enlisting in the Army and later embarking on an illustrious career in law enforcement. Throughout his life, he articulated a “vision of policing that was a nonpartisan public servant committed to the betterment of society,” as historian Sam Walker puts it. His career reflects a focus on evidence-based, community-oriented policing, breaking radically from the often-corrupt patronage system. During his career as a police chief, Vollmer pioneered several innovations in police use of technology, operations, training, and hiring standards. Through extensive academic writings, he set forth a path for effective, just policing that remains viable today. He was a forward-thinking reformer willing to take unpopular positions, often at great personal cost.

Vollmer’s military experience left an impression on him, but the revisionists overstate its influence on his career. He served only one year in the Philippines, during the Spanish–American War, mostly on a gunboat on an expeditionary mission seeking the assistance of the pro-American Macabebe kingdom. Go claims: “As part of the occupying force in Manila, [Vollmer] had been among the few soldiers charged with policing the city of Manila.” But no evidence exists that Vollmer played a major role in policing Manila, beyond routine peace patrols typically conducted by occupying forces. (It’s worth noting that, prior to the U.S. occupying Manila during the Spanish–American War, a highly unpopular Spanish colonial government controlled the Philippines.) Neither major biography of Vollmer—whether O. W. Wilson’s in 1953 or Willard Oliver’s in 2017—suggests that his military service was a major motivator of his policing career. Indeed, Oliver even notes that military patrols in the Philippines wore local clothing to avoid appearing as an occupying force. Go quotes Oliver’s work, but he appears unaware of these details.

How influential were military techniques on the twentieth-century modernization of U.S. police that Vollmer inaugurated? Vollmer did suggest in his writing that “military science” stressed the importance of screening criteria for officers: physical fitness, mental ability, emotional maturity. He also introduced such military-like tactics as using the locations of crimes on a map to determine where to focus policing efforts. But his emphasis on public engagement, humane treatment of offenders, and crime prevention contrasts starkly with the allegedly militarized model of policing that today’s revisionists condemn. Any genuine military influence related more to formal and procedural policies, from recruitment and drilling to order and command structure.

Vollmer’s path into policing was also more organic than the current narrative about him suggests. After serving as a mail carrier upon his return to Berkeley from the Philippines, he was encouraged by a local newspaper editor and others to run for elected office as town marshal. (The incumbent marshal was known for taking bribes to ignore local vice.) Vollmer’s family urged him not to pursue a job in law enforcement, as the field was notoriously corrupt. Vollmer ignored their advice and was elected in 1905. In 1909, Berkeley created the position of police chief, and Vollmer became the first to hold the office.

Vollmer’s early years foreshadowed the innovations in policing that he was soon to develop. He was especially interested in gaining public respect for his office and his deputies. He ordered raids on Chinese-run “opium dens,” though only after strong community pressure. But he did not always follow the voice of the people; he frequently sought to handle situations using unconventional de-escalation techniques—with student rioters, for example. One might say that his approach embodied the principles of what today we call “community policing.”

From the beginning, Vollmer was keen on experimenting with new policing methods. He tested putting officers on bicycles before implementing the policy citywide in Berkeley. Similarly, he tried using call boxes before persuading the city to invest in them on a larger scale. His awareness of time-motion research drove his efforts to enhance police-response times. Vollmer was also the first police chief to suggest what would later be recognized as a “public health model” for violent crime. He hired one of the first female police officers in the United States; she had a background in social work.

Vollmer was also the first police chief to emphasize rigorous training and education. He established a summer police-training program at the University of California, Berkeley, which all officers had to complete. This program became the precursor to degree programs at other universities and to Berkeley’s School of Criminology. Vollmer was the first police chief in the United States to require officers to obtain a college degree.

Those who see education as a means to improve policing and support evidence-based decision-making have Vollmer to thank. At Berkeley, he devised a pre-delinquency program, seeking to track kids at risk of committing crimes (based on school officials’ reports and psychological and sociological factors). Officers would assign different categories to each household, and then collaborate with social workers and school officials to create intervention plans. Vollmer also created a modus-operandi algorithm to determine whether crimes were linked to a common perpetrator. While the algorithm’s mathematical execution may seem rudimentary by today’s standards, the concept was remarkably forward-thinking. Vollmer also championed regular community engagement, encouraging officers to have meals with residents and participate in neighborhood activities.

From today’s perspective, the education that Vollmer offered might seem outdated, even offensive, in parts. Go notes witheringly that students at Vollmer’s summer police-training program took courses on “racial types” and theories of “heredity” and “race degeneration” as causes of criminality. Yet these topics, listed under the course “Criminology, Anthropology, and Heredity,” reflected the theories of the era. In any case, most of the curriculum focused on forensics, law, and policing procedures. By the 1930s, when Vollmer developed a two-year police-education curriculum for San Jose State and Cal State–Los Angeles, the coursework on crime causation was presenting traditional psychological and sociological claims.

Indeed, Vollmer was ahead of his time on racial issues. He was one of the first police chiefs to hire a black officer, bringing Walter Gordon, the first black football player at UC-Berkeley, on board in 1919. When Berkeley officers complained to Vollmer about having a black colleague, Oliver relays, Vollmer told them that they were free to resign. Vollmer’s commitment to police diversity is also reflected in his writings, including a passage from a chapter in the Wickersham Commission report on police, which he led as the principal author: “In view of the diversity of non-English speaking nationals resident in our large cities, it seems to us important to suggest that more police officers should be on each force who are of such races and familiar with their language, habits, customs and cultural background.”

Vollmer steadfastly opposed the use of torture to obtain confessions, and he banned it in the Berkeley Police Department. He also opposed the death penalty when it appeared on the ballot in California, arguing that it was not an effective deterrent. He contended that the certainty of punishment was more significant than its severity, supporting his argument with comparative statistics from cities, states, and countries that did not use capital punishment.

Vollmer’s enlightened influence did not extend as far as it might have. His tenure as LAPD chief lasted just one year, ending after he clashed with political leadership over efforts to build a humane county jail and root out departmental corruption. His tumultuous year in Los Angeles is the one time that Vollmer can be said to have turned to military-type tactics, what he called “war fighting”: he used crime maps strategically to deploy a roving group of officers near banks frequently targeted by robbers and cracked down on illegal gambling houses and speakeasies.

But numerous reforms that Vollmer advocated were never fully implemented in other cities. Consequently, police forces in many cities continued to reflect partisan interests; many departments were eventually captured by collective bargaining. Court rulings in the 1960s allowed police in American cities to unionize, with police unions protecting cops’ interests and resisting reform.

None of this can be pinned on Vollmer. Some of his writing may be dated, but his record suggests neither racism nor advocacy for “militarized” policing. Despite having obtained only a seventh-grade education, Vollmer became a prolific writer, a leading police chief, and a professor at the University of Chicago and UC-Berkeley. The weight of the evidence indicates that he took risks in his career to advance diversity and professionalism in policing.

Vollmer committed suicide in 1955 after battling cancer and Parkinson’s disease. He left behind a legacy of vital ideas and talented protégés who helped launch criminology and criminal-justice programs in colleges and universities. The United States would not have criminology and criminal-justice degree-granting programs if it weren’t for his efforts in the 1930s. Without Vollmer’s work, the education opportunities for those pursuing a law-enforcement career in the United States might look more like those in Europe, where police education is taught solely in training academies.

American police have not always been at the forefront of innovation and evidence-driven practices, but this, too, is not Vollmer’s fault. To the extent the responsibility lies in an overly fractured system of policing, Vollmer was, once again, a force for good sense. He argued for the centralization of police into state police agencies, not to eliminate local autonomy but to boost the overall quality of training and standards. The model that Vollmer had in mind looks similar to that of the United Kingdom today.

The attacks on Vollmer’s legacy are clearly propaganda—part of an effort to delegitimize policing in the United States. When academics conclude that distinguished figures from the past don’t measure up to today’s standards, they try to discredit their whole body of work and deny that any progress has occurred. Criminology is an applied social science, committed to studying criminal behavior: its causes, the social reactions to it, and the systems designed for combating it. That was the focus of the Berkeley School of Criminology that Vollmer helped found. Unfortunately, starting in the late 1960s, it abandoned its commitment to applied science, became tied to the antiwar movement and radical elements in the discipline, and lost support from distinguished alumni.

Rewriting police history to undermine any acknowledgment of progress and moving away from applied social science in favor of political agendas is a bad path for academic criminology. This approach is likely to result in political backlash and devaluation of criminology as a field. It is also dishonest in its misrepresentation of the legacy of August Vollmer, an American hero of public safety.

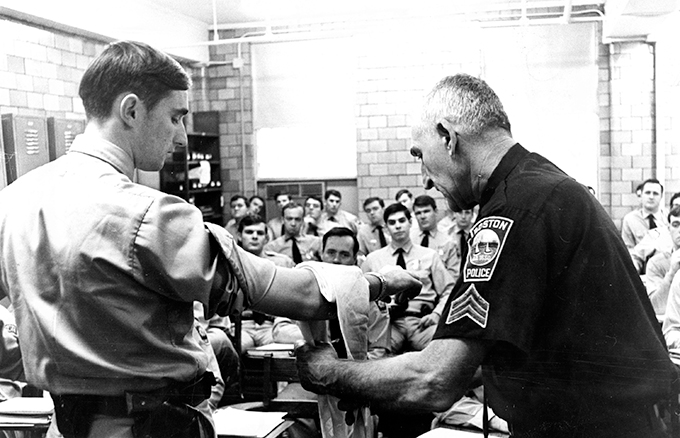

Top Photo: August Vollmer, chief of police in Berkeley, California, from 1909 to 1932 (Archive PL / Alamy Stock Photo)

Source link