The story begins like any other New York art story of the midcentury: the young Missourian Paul Jenkins, a GI Biller at the Art Students League on West Fifty-seventh Street, encounters the work of Jackson Pollock and resolves to accept its “cataclysmic challenge.” On its face, this makes for an unremarkable addition to the era’s litany of dewy-eyed novices galvanized by Pollock’s explosive theatrics. But Jenkins is tied up with Pollock in unusual ways. In the spring of 1956 Jenkins, who had by this time moved to Paris, shown solo in New York, and exhibited at MOMA, visited Pollock at his studio on Long Island. He left him with a copy of Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, still retrievable on the shelves of the Pollock-Krasner house in Springs. A few months later, Lee Krasner was traveling through Europe and decided to stay a while at Jenkins’s studio on the rue Decrès. There, she received a phone call from Clement Greenberg informing her that Pollock had died.

That’s one origin story. Look closely at the details and you’ll find a few clues about Jenkins’s life and work: the early infatuation with Abstract Expressionism before his movement away from it, a preoccupation with Eastern wisdom, the collegiality between Jenkins and his peers (Rothko and de Kooning considered him their equal), the va-et-vient between Paris and New York, and his feeling for the ecstatic and the desolate. The paintings now exhibited at Timothy Taylor in Tribeca communicate some of this layered personal history.

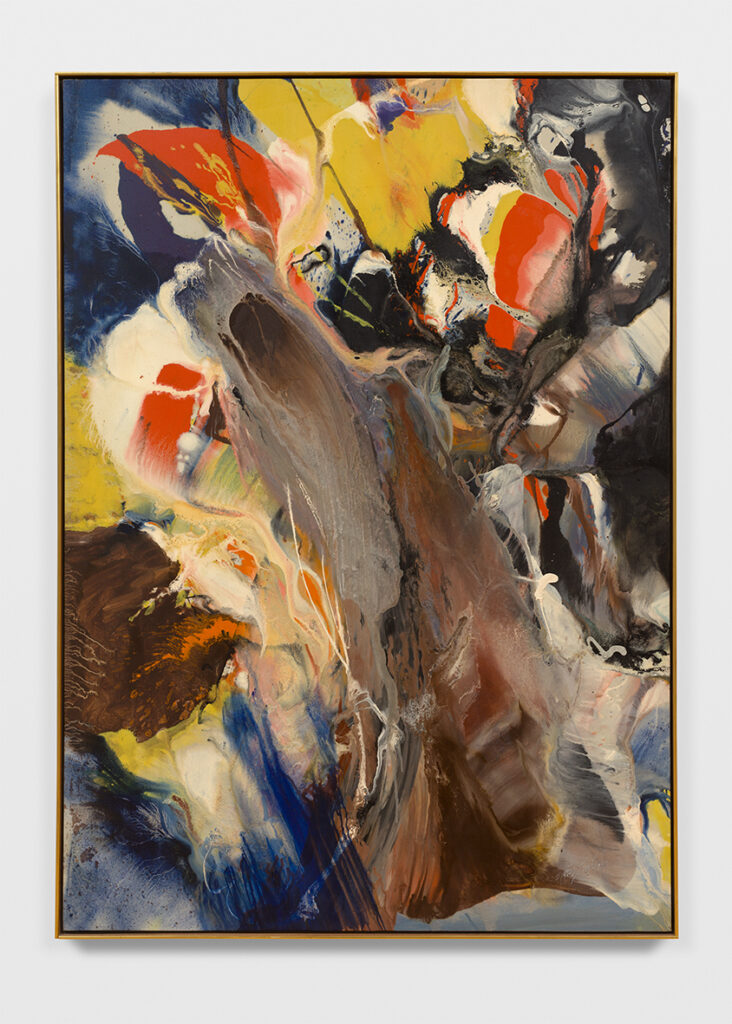

The earliest of them, completed in 1959, is a dizzying but compelling work of expressionistic panache. Jenkins layers a series of splotches, fields, and waves that coalesce to form a superimposition of painted statements. The canvas is crowded with voices gasping for air. Flashes of gold and red-orange given you something to hold onto; otherwise your eyes would follow the maze of shapes and splashes right off the edge of the image. Though its happenstance effects make for pleasurable viewing, this is a far cry from Zen in the art of painting.

The following year saw two key developments: Jenkins began using acrylics, and he decided to precede all of his titles with “phenomena.” More on the latter in a moment. As for the former, if anyone was born to use acrylic, it was Paul Jenkins. His signature method began with a primed white canvas on which thinned acrylic was poured, usually from the corners. He directed paint across the surface either by utensil (almost every article on Jenkins mentions his trusty “ivory knife”) or by manipulation of the canvas. Acrylic thus thinned, flowing on canvas thus primed and handled, does peculiar things. It might pool, run, bleed, separate, release its luminosity, devise new hues, create rhythm and atmosphere. It has its own voice, and here it was liberated to speak.

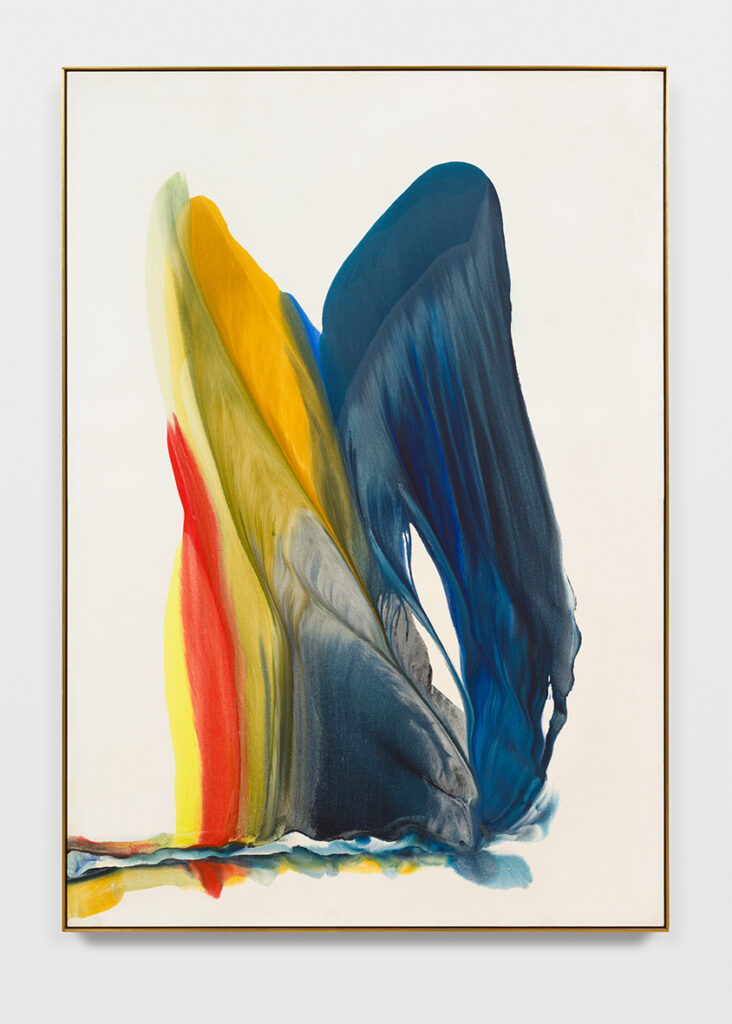

This was Abstract Expressionism in theory but more like Tachisme in effect. Viewers of the exhibition at Timothy Taylor will intrinsically feel the difference. The works have a plain-spoken, earnestly lyrical quality that avoids the excessive self-consciousness of much of Abstract Expressionism. Phenomena Length of the Wind (1976), seeming to represent a sprouting flower or a pair of wings flaying off from the middle of the canvas, revels in its rather straightforward chromatic effects. Did Rothko or de Kooning ever revel in anything?

Of course, Jenkins’s approach came not without its drawbacks. For one, very little texture or depth could be lent to the canvas. Phenomena Estuary (1978) demonstrates the double edge of Jenkins’s method. Warring color fields attempt to create a frisson of tension, but the canvas is too flat to support it. The cadmium-yellow core of the painting is gorgeous, but its surrounding color reminds you of salmon left out in the sun too long. In Jenkins’s paintings, one is drawn in and then repelled. No feelings last.

Which brings us to “phenomena.” Jenkins knew his paintings trafficked in fleeting impressions. “One watches them,” said Jenkins; “one doesn’t look at them.” John Berger called them “nomadic.” Such a mercenary approach can, of course, leave a viewer rather cold. Phenomena Rain Palace (1976) is beautifully manufactured but has very little feeling to it. It offers you a succession of briefly graspable sense memories—clouds passing overhead, fog sweeping into view, a rainbow glowing in the distance—and then retracts that offer immediately. The issue is the sallowness of the canvas, the self-evident fact that the painting is not really painted at all. It seems too easy, too effortless, as fleeting as the clouds.

But there is something undeniably enticing about Jenkins’s work—call it the intrigue of contradiction. An example: Jenkins’s forms, flat and thin though they are, demonstrate a longing for shape, an element you might call sculptural. It is probably relevant that, while an art student in Kansas, Jenkins worked weekends and summers at a local ceramics factory. In the early 1970s, Jenkins began developing monumental sculptures in limestone and steel. Most of the work at Timothy Taylor comes after this. Phenomena Samothrace Arch (1973) evinces Jenkins’s innate feeling for sculpted forms. Here he comes tantalizingly close to creating a three-dimensional effect: you almost sense that, if you move around the gallery, you might see some new side to the object at the heart of the canvas.

Mostly, however, the works cannot help but own their two-dimensionality. Indeed, one thinks often of the terse, planimetric stylings of Oriental art—and with good reason. In his student days at the Kansas Art Institute, Jenkins was a regular patron of the extensive Asian wings of the Nelson-Atkins Museum. At around the same time he encountered the Tao Te Ching, awestruck by its “masterpieces in simplicity.” The Pollock business may be catchy, but here was the real origin story, the real birth of a sensibility: color, simplicity, scale, tranquility, spiritual resonance. His travels to Japan in the mid-Sixties impressed upon him the viability of harmonizing a built environment with a sacred one. His next stops were Bombay, Agra, and the caves of Aurangabad. Again, he could only marvel at the sight of such lurid color against so ancient a landscape.

His work thereafter bears this imprint. On large-scale canvases, he used pure white backgrounds to frame the colorfully molded, somewhat elusive figures at the center. In its compactness, the crystalline focus of its bounding lines, and its entirely unified approach, Phenomena Mount Sinai (1972) has something of the great gemlike Tang poems or the Japanese concept of shibui: a beauty so refined it becomes almost silent. Just as it withholds its mysteries, the painting also emanates a real, legible depth. Colors spontaneously produce secondary, tertiary, even quaternary effects. If it’s not exactly Zen in the art of painting, it’s not so far off. You can become consternated at the earnestness of the ideas, even grow frustrated at the ephemerality of Jenkins’s effects. But color, in its wordless language, has a way of persuading all on its own. That Paul Jenkins, a product of the egotistical New York art world, learned to get out of the way and let his colors do the talking seems, all things told, a not-inconsiderable achievement.