Waiting on the Moon: Artists, Poets, Drifters, Grifters, and Goddesses, by Peter Wolf (Little-Brown, 335 pp., $30).

In his elegant memoir of postwar Greenwich Village life, When Kafka Was the Rage, the literary critic Anatole Broyard wrote that “you could always find your own life reflected in art, even if it was distorted or discolored.” Broyard then cited one sentence from a book on surrealism that struck him: “Beauty is the chance meeting, on an operating table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”

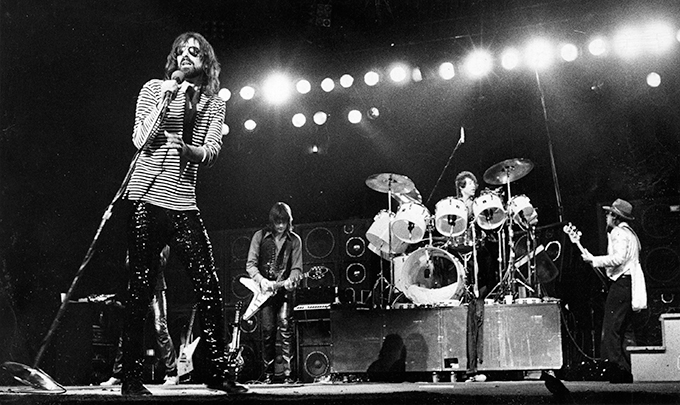

Such surrealism—or the chance encounters once common at bars, shops, and cafes—might also fit to describe Peter Wolf’s life in his memoir, Waiting on the Moon. Wolf has had a long solo career, but before that he was the lead singer of the J. Geils Band, the Worcester-based rock and blues group known for its live gigs and cheery Top 40 hits in the 1970s and early 1980s. The band is best remembered for “Centerfold,” its sole Number One hit, with its playful music video that debuted right after MTV’s launch in August 1981.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The band itself, which fell apart in 1983, serves as a distant backdrop in Wolf’s memoir. The book is less a reflection on his own life than a series of poignant, Runyonesque vignettes featuring celebrities, has-beens, nobodies, and those in between—figures he encountered from childhood onward in the cities that shaped him. In writing the book, Wolf said he was guided by a line from Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin: “I am a camera with its shutter open.” He succeeds by presenting vaudevillian reels that reveal the quirks and eccentricities of both famous and forgotten characters navigating the gritty urbanity of mid-century life.

Wolf’s chance encounters began in his formative years, in his family’s small Bronx apartment, where his parents immersed him in bohemian life. His mother was an intellectual, more interested in reading than housekeeping. His multilingual father was a gifted singer and “an incredibly artistic spirit,” who strolled around with a cigarette holder but rarely concerned himself with making money.

Their shared passion for culture set the stage for many of Wolf’s more striking childhood moments. In one instance, they took him to see a French film about Christ’s Passion. “A woman in a mink coat and a tall man in glasses rushed into our row,” Wolf recalls. The perfumed woman—Marilyn Monroe—sat beside him, resting her head on the young Wolf’s shoulder and dozing off. Her then-husband, Arthur Miller, sat beside her. Wolf, equally bored, soon fell asleep as well. In another encounter, Wolf’s father, who sang with a renowned choir in Massachusetts, often left him at a local artist’s studio. The “thin, kind, bespectacled . . . very friendly” man who welcomed him was Norman Rockwell, who gave him paper and pencils to draw.

Wolf’s parents introduced him to Greenwich Village, then the center of a blossoming sixties-era folk and jazz scene. It was here that Wolf’s “adventurous teenage spirit, always seeking art and music, found its home.” He describes the musicians, often traveling from suburbs, who performed at the venues between MacDougal and Bleecker Streets that “supported the talented (and sometimes not-so-talented) . . . who were playing jazz and folk music rather than the formulaic pop sounds of the day.” In a Village record shop in 1961, Wolf, who started cultivating a love for the blues by his late teens, found himself transfixed by an unusual voice singing at the back of the store. The front desk worker, a banjo player, informed Wolf that it belonged to “some new kid” named “Bobby Dillon.” He recounts one moment when Dylan—“I could almost feel those steel-blue eyes blazing right through his dark Ray-Bans”—angrily dressed down an intoxicated Wolf, who had just asked him, “What is truth?”

Later, in November 1963, as Wolf learned about John F. Kennedy’s assassination from paperboys shouting near a hot dog wagon by St. Patrick’s Cathedral, he felt “an imperceptible change within me, as if the ground had slightly shifted and somehow I needed to find more stable footing to keep from feeling further adrift.”

Wolf began visiting colleges, faking his enrollment as an art student, until he was at last admitted to an art school in Boston. There, the disheveled Wolf found a roommate—a preppy, straight-laced guy named David. He compared the differences between them to “those of Gauguin and Van Gogh.” His roommate’s “staid demeanor,” however, changed one night when he screamed after finding part of a cockroach caught in his toothbrush. “I like to imagine that this helped inspire the surrealist aspects of many of his defining films,” writes Wolf of filmmaker David Lynch, who died earlier this year.

It was around Boston that Wolf’s musical career and artistic interests began to flourish. In the 1970s, “Harvard Square, in Cambridge, was like the Left Bank of postwar Paris,” he writes, full of cafés and studios. “You could see Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, Kurt Vonnegut, Al Capp, John Berryman, Edwin Land (inventor of the Polaroid camera), and Jorge Luis Borges if you kept your eyes open.”

In the Boston area, Wolf also met and grew close to his musical idols—blues legends like Muddy Waters, for whom his original R&B band, the Hallucinations, opened, and John Lee Hooker (“I’m bad like Jesse James”), who once confided his love for the TV show Lassie.

In Cambridge, Wolf became close with Ed Hood, the Warhol Superstar, who introduced him to a wide range of literature. After seeing a sold-out J. Geils Band show, Hood “languorously smoked his cigarette, turned to me before the encore, and proudly said, to my surprise, ‘My student, you’re becoming a star.’” Wolf, in turn, as a graveyard shift radio DJ on WBCN, helped cultivate the stardom of Van Morrison—then struggling and “looking for gigs”—whose wife would send postcards requesting that the radio station play her husband’s songs. In time, there would be more gigs, and stardom, for both Wolf and Van Morrison.

Wolf captures a range of mid-century urban scenes, each one distinct—from the studio intrigue and celebrity gatherings of Los Angeles, like those organized by record producer Earl McGrath, to an evening in Paris, where he and a young Jerry Hall spotted an elderly Jean-Paul Sartre watching a TV in his apartment. “Only in Paris could one see an incongruous sight such as a great philosopher in front of the television,” Wolf writes.

As he toured and hustled for performing opportunities and better record deals, Wolf crossed paths with other characters. Some, like John Lennon, were already legendary. Others were in their twilight, like Alfred Hitchcock. And some, like Tennessee Williams, were possessed with the wisdom of disappointment. After Wolf’s divorce from Dorothy Faye—also known as Faye Dunaway—Williams advised him: “Peter, the heart survives, but it’s the deep scars that will remain, like a lover’s initials carved on the trunk of an old maple tree.”

Beyond the catalogue of anecdotes and cultural icons, Wolf’s memoir becomes an elegant reflection on postwar America, tracing the decades between the end of World War II and the 1980s. His book joins a growing library of reminiscences by rockers now nearing their expiration dates.

Many of these musicians remain active. Eric Clapton, once too stoned to realize he was being introduced to Muddy Waters—a major influence on his band Cream—is on a global tour at age 80. Mick Jagger, now 81, recently announced his engagement to his longtime partner, age 37. Wolf recalls being “awed by Mick’s extreme discipline” when J. Geils opened for the Rolling Stones in the 1970s. Jagger’s Stones bandmate, Ronnie Wood— “friendly as always,” as Wolf remembers him—now spends his days painting in the style of Caravaggio. “I get so obsessed with an idea that I go in and start on a canvas and sometimes I’ve been there for hours and I realize I haven’t even taken my jacket off. It’s what life is all about,” Wood recently told The Times.

Such sentiments characterize Wolf’s book. Waiting on the Moon is a manual to the lost art of hanging out and staying to see who shows up.

Top Photo: Peter Wolf performing in 2024 (Scott Dudelson/Getty Images Entertainment via Getty Images)

Source link