In any age, the significant individuals tend to be those who invent or seize upon a new means, a new medium, a new method, a fresh voice or device, and embody or exercise or exploit it to the fullest. Those favored few become emblematic of their time, while countless others are forgotten—not only the mediocre or talentless but also people of real ability whose work is less boldly new or, in being original, less masterful; who may, even as they go down to obscurity, console themselves with the belief that they are keeping up standards, forming a bulwark against the flood tide of gross modernity. Too staid or too myopic, they already have their reward, which is not to have been misunderstood. They have failed to define the age. Gustave Flaubert—herald of modernism, obsessive word-hound, and austere champion of l’art pour l’art—was the other, rarer sort: the sort that, having broken new ground and redefined a field, belongs to posterity.

From the start, Flaubert’s methods and maladies were his own. He could spend six hard weeks on a few dozen pages, or two torturous days reworking a single paragraph. His feeling for prose verged on, and perhaps crossed over into, the synesthetic. The text was alive for him, not only in its particulars—the much-vaunted mot juste, which, like a lepidopterist hunting for shadow-box specimens, he sought and displayed in sentence after dazzling sentence—but in its structure, its rhythms, its sovereign colors. Madame Bovary, a novel of bourgeois disillusionment, was a musty shade for him; Salammbô, his opulent epic of ancient Carthage, was purple. Even in the absence of dramatic action (“ideas are action,” he maintained), he believed that the internal strength of his style was sufficient to cement his blocks of narrative in the reader’s mind.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The work inflamed his brain, upset his digestion, played havoc with his nerves. Yet days off were nearly unthinkable. Oceans of tedium, deserts of difficulty had to be crossed. To get the details right in his fiction, Flaubert consulted experts, visited key sites, scoured old newspapers, and devoured hundreds, perhaps thousands, of books. “He felt of his vocation almost nothing but the difficulty,” judged Henry James, another confirmed bachelor wedded to his pen. Even Flaubert’s early letters to a mistress, Louise Colet, brim with the agony and ecstasy of a literary life, from an encomium to Shakespeare (“So what the devil do you want me to talk to you about if not Shakespeare, if not what lies closest to my heart?”) to angst over whether any of his writings would ever be published. His calling ate up his life, and as the years passed, his grounds for worry and complaint hardly lessened. To novelist George Sand, in 1867: “As I advance, new difficulties arise. It’s like dragging a heavy cartload of stones.”

Did he protest too much? Earlier that week, he had attended a ball at the Tuileries and met the Russian czar, whom he found boorish. Soon, however, he was back at work. He kept on dragging his cartload: five years for Madame Bovary, seven for Sentimental Education, working fervently at the large round table in the middle of his study, dipping his quill—he detested metal-nibbed pens—into an inkstand shaped like a toad, and sleeping off the fever of composition on a camp bed heaped with cushions that he made up in one corner.

All that strenuous effort would have been waste and welter were it not for what it produced. Just as Flaubert intended, you can feel almost physically the things he describes. Even small domestic scenes in his celebrated first novel, Madame Bovary, are heightened by an acuteness of vision so that they seem acts not of invention but of observation, a comprehensive noticing:

Through the cracks in the wood, the sun stretched out its long thin rays on the flagstone floor, shattering against the corners of the furniture and trembling on the ceiling. Flies were climbing the length of the glasses left on the table, and buzzing as they drowned at the bottom, in the cider’s dregs. . . . Between the window and the hearth, Emma was sewing; she wore no shawl; you could see on her bare shoulders tiny drops of sweat.

The drowning flies, like the erotic touch of Emma Bovary’s sweat, are an inspired detail, one of countless that enrich a narrative that keeps threatening to dissolve into melodrama but does not, cannot, because of Flaubert’s unerring control and the ironic voice that superintends every scene—romantic scenes, especially. Even as he borrows the romance genre’s tropes and apes its language in the speeches of his mendacious lovers, we see through their pitiful stratagems: we laugh as a Lothario drips water onto a kiss-off letter to fake the tears that he hasn’t cried; we know what Emma really has in mind while angling for weekly “piano lessons.” Yet because these are lives seen close-up, with a salt tang as of real sweat, Madame Bovary has the shape finally not of satire or of comedy, but of tragedy.

“An author in his book must be like God in the universe,” runs Flaubert’s famous dictum, “present everywhere and visible nowhere. Art being a second Nature, the creator of that Nature must behave similarly.” His whole life was marked by this combination of supreme ego and self-effacement. Giving to modern literature its foremost commandment—overt authorial intrusions, especially the moralizing of a George Eliot, were out—he also claimed for himself the role in his fiction of that deity who, scripture says, numbers the hairs of every head and notes the smallest sparrow’s earthward swoon. Houseflies, carriage horses, peasants, horny servant boys and lame stable hands, innkeepers and provincial tax collectors, blowhard politicians and men of progress, worldly priests, badgering or blasphemous in-laws, suffering wives and their seducers—their lives are not insignificant because Flaubert (whatever his personal antipathy for the bourgeois mind and milieu, a constant refrain in his correspondence) draws them all into the spotlight of his attention, now panoptic and diffuse as a pale winter sun, now microscopic and merciless as an interrogator’s lamp. They do not go unwitnessed because Flaubert witnesses them for us with dispassionate intensity.

Here, Emma burns her old marriage bouquet:

It blazed up faster than dry straw. Then it was like a red bush on the embers, slowly consuming itself. . . . The little pasteboard berries flashed, the brass wires writhed, the lace melted; and the paper florets, all shriveled up, swaying along the fireback like black butterflies, finally flew away up the chimney.

To be so closely observed seems intolerable; yet, according to most world religions, this is the surveilled state in which we all live. In the unsparing light of Flaubert’s mind, Emma Bovary dissembles, runs amok, goes mad—as he went a little mad himself. While writing of her poisoning, the novelist—tasting arsenic on his own tongue—“was poisoned so effectively” himself that he vomited up his dinner. Twice. “The characters I create drive me insane,” he confessed. “They haunt me; or, rather, I haunt them: I live in their skin.”

Flaubert was born in 1821 in the cathedral city of Rouen. His father, an eminent surgeon, housed his family in the domestic wing of the municipal hospital, from where his two sons and daughter could hear the moans of the sick and, climbing their garden trellis, peer down into the operating theater to watch their father dissecting corpses. As a teenager, Flaubert paid visits to the morgue; when he was only six or seven, an uncle gave him a tour of the local insane asylum. Given this upbringing, the adult Flaubert’s jaundiced view of life is small wonder; understandable, too, is the radical opposition he maintained between life and Art (which he capitalized). Faced with flyblown cadavers and screaming women chained in cells, what sensitive child would not retreat into reading and reverie? In art, he found an enduring beauty with which to arm himself against the world’s ugliness. Nevertheless, he claimed, not without irony, that such disturbing impressions at a young age “make a man of you.”

Tall and athletic for the time, blue-eyed and fair, but living in the shadow of a brother nine years his senior, whom their father groomed for a career in medicine, Flaubert grew inwardly like a forked tree, split between romanticism and naturalism. From age 11 on, as a boarder in the local lycée, he read Chateaubriand, Hugo, and the French Romantics; like his classmates, he adopted Romantic ideas and poses. Politics and all that was ephemeral bored him; his feeling for France as the fatherland, la patrie, was ambivalent, at best; he declared himself “the brother in God of everything that lives.” His sympathy extended through the whole annals of the past, but he could scarcely fathom the lives of contemporaries who had no feeling for art. “Between the world and me there existed a kind of stained-glass window,” he said. A journey at 18 to Corsica via Provence, where he saw the Mediterranean and ancient ruins for the first time, only fed his hunger for a more dramatic life. He began writing, but was soon thrust, at his father’s insistence, into the study of law, which he loathed. The “perpetual fury of work” as he crammed for examinations brought on attacks of epilepsy, which, at 22, got him off the hook for good; he was allowed thereafter to devote himself to literature.

The family’s country house at Croisset became his redoubt. Ensconced there in comfort, he convalesced, daydreamed, read voraciously, produced juvenilia. His idols were Homer, Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Rabelais, whose work, tellingly, he admired for being “pitiless.” Flaubert, of whom the prominent literary critic Sainte-Beuve would say that he wielded his pen like a scalpel, and of whom a caricature would show him holding Emma Bovary’s impaled and bleeding heart, was contemptuous of “socialist humanitarian writer[s]” who demand of literary productions that they serve the cause of Progress.

A handful of experiences, alternately crushing and invigorating, prepared Flaubert by the end of his twenties to begin Madame Bovary. First, in early 1846, came the twin tragedies of his father’s and sister’s deaths, followed by the intense, exasperating love affair with Colet, a married woman and minor poet 11 years his senior; the clotted, passionate letters Flaubert wrote to her, unlike any others in his life, contain some of his most penetrating statements on literature. Yet she gave him no peace, demanding constant proofs of affection and complaining bitterly that he talked too much art. He reproached her, in turn: “It takes courage to write to you, knowing that whatever I say wounds you.” She pressed him for a commitment; the idea of a child struck him as “an appalling threat to my happiness.”

Promotional materials for the wonderful one-volume NYRB Classics edition of Flaubert’s letters, published in 2023, call Colet “the love of [his] life”; his own testimony is far more ferocious: “I am sick and my sickness is you.” She would later write a pair of novels depicting a Flaubert stand-in unfavorably. Just as Emma Bovary in her coffin may not have worn her wedding dress had Flaubert’s sister Caroline not been buried in hers, Emma’s selfishness, sensuality, and vanity are traceable, at least partly, to the high-strung Colet. When their relationship ended in 1848—another of her lovers had gotten her pregnant—she resolved to dedicate herself to her writing. Flaubert’s friend Maxime Du Camp had the parting shot: “Bad news for literature.”

Flaubert would soon leave with Du Camp on an 18-month tour of the Orient—another formative experience—but not before he got some bad news of his own. In April 1848, his friend and fellow aesthete Alfred Le Poittevin died; for two nights, Flaubert watched over, and finally helped to enshroud, his corpse. “The body of the man I loved best in the world practically fell apart in my hands,” he recalled years later. “Once you have kissed a corpse on the forehead, something of it always remains on your lips—an infinite bitterness, an aftertaste of annihilation that nothing ever effaces.” This death, too, he translated into fiction. A letter: “From behind, I saw the coffin swaying like a rolling boat.” Madame Bovary: The coffin “advanced by continual jerks, like a launch that pitches at every wave” (one among several such details). It was his rule not to put anything of himself into his narratives, “and yet,” he confessed, “I have put in a great deal.” This is Flaubert’s secret strength: not that he eliminated himself as an author but that he was merciless with the material of his life.

There were missteps. Flaubert had high hopes for The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a long work dramatizing the fourth-century saint’s mental fight against a hallucinatory host of Christian heresies, pagan doctrines, and fleshly sins. He read scores of texts while composing its episodes, consulting ancient histories and scholarly commentaries. This was his bombastic side; one may wonder how his friends stood it, listening for 32 hours (so Du Camp recalled), while Flaubert declaimed his oneiric drama. When it was over, Louis Bouilhet rendered the verdict: “We think you should throw it into the fire and never speak of it again.” Flaubert was crushed. The book would appear only decades later, drastically shortened and revised.

Fortunately, he had the trip to distract him: Alexandria, Cairo, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Athens, returning by way of Rome and Naples—worlds impossibly remote from his provincial Normandy. If there is some truth to D. H. Lawrence’s judgment that Flaubert “stood away from life as from a leprosy,” you wouldn’t know it from the rumbustious, often salacious, letters of his excursion to the Middle East. For once, he flung himself into the thick of it—this being, quite often, whatever nubile body was near at hand. On the rebound from Colet, Flaubert—fornicating across the Levant—was free to indulge his unsentimental lusts.

When they weren’t pursuing various lubricities, he and Du Camp (“We look quite dashing and are quite insolent”) made time to bathe in the Red Sea, take in the moonlit ruins of Thebes, view the Sphinx and pyramids whitened by eagle droppings, and, in Jerusalem, tour the contested Holy Sepulchre, which Flaubert found off-putting in its commercialized clamor. Du Camp snapped pictures of monuments, and they commissioned translations of stories and songs—“everything that is most folkloric and oriental.” Armed with letters of introduction to Egyptian officials, they partook of society both high and low, Flaubert glorying in the sun and open air—noting, too, the dead camels that one sees on the desert, their guts torn by jackals. “I gulped down a whole bellyful of colors,” he wrote his maman, the experience as revelatory for him as was, for the philhellenist Yukio Mishima, his first visit to Greece and Italy in 1952. If Flaubert was feasting, “afterwards the digesting will have to be done,” he admitted, “then the shitting; and the shit had better be good! That’s the important thing.”

While Flaubert was abroad, Honoré de Balzac died. A massive presence, the author of The Human Comedy—an interlinked sequence of some 90 novels and stories depicting the rise of capitalism and decline of the aristocracy—was suddenly gone, leaving a vast absence in French letters. Flaubert’s own ambition rose to fill it. He had long wished to make his literary debut “in full armor”—or not at all. He had hoped that Balzac would approve of him. In Madame Bovary, he, too, took the bourgeoisie as his subject, but he strove for totality not as Balzac did, through a kind of artless “amplitude,” a mania for getting everything in—the first drafts of Balzac novels sent to the printer as much as quadrupled in length by the time they were published—but through the strategic deployment of precise details, the unambiguous rightness of each chosen phrase. Like the stippled colors of a pointillist painting, Flaubert’s descriptions of people, landscapes, furnishings, city scenes, and psychological states remain discrete but gel in the mind into a brilliant whole.

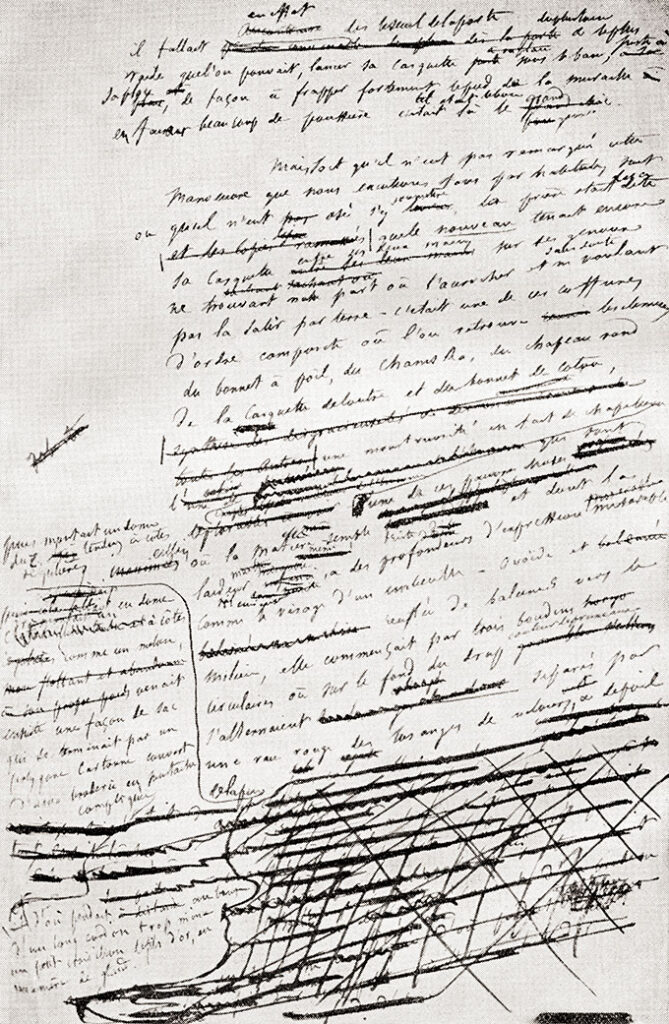

Madame Bovary first came out in serial format in La Revue de Paris, where Du Camp sat on the editorial board, but unlike the baggy narratives of Charles Dickens and other writers of the time, Flaubert’s novel—in keeping with his perfectionism—was already finished by the time the first installment appeared. It did not grow in the telling. Instead, Flaubert ruthlessly winnowed: in 2009, some 4,500 pages cut from, or revised for, the published text were released online. Each page of the finished novel was the result of at least four, and as many as a dozen, rewritings. He had learned from the Saint Anthony disaster; such objectivity toward his own work was now the inner style of the man. “Style underlies words as much as it is embodied in them,” he wrote. “It is as much the soul of a work as its flesh.”

Flaubert slips almost imperceptibly between distanced, “objective” narration and the inner lives of his characters. This is his central innovation, crucial to modern novelists. So effective was the technique at conveying the undiluted mind of a fallen woman (some of Emma’s antipathy for her bourgeois environs was, in fact, Flaubert’s own: “Emma Bovary, c’est moi”) that his novel was put on trial as immoral, as if to confirm his loathing. The book was successfully defended in 1857 as a cautionary tale for young women and became a bestseller. Lost on both sides of the argument was its art, the perfect sentences that Flaubert for five years had slaved over. His writings, Marcel Proust said, are “without precedent in our literature.” Flaubert brought to prose narrative the lyricist’s concern for tone and form. Each word had to be pitched at the right register and suit the perspective that it came from. Form and substance in a given sentence were, for him, inseparable. As if this weren’t enough to vex translators, Flaubert weaves a complex dance of tenses—the perfect past arising amid the continuous past, the simple past dissolving into the present. Grammatical beauty, Proust called it, and he was right.

The bourgeois fascinated Flaubert. Against his will, he couldn’t look away—or not for long. He’d had his doubts all along about writing a “rational book,” however. He felt the need for “gigantic epics.” So long suppressed, this need finally burst forth in the overheated exoticism of Salammbô. Set during the ancient Mercenary War, when hired soldiers who had fought alongside Carthage in the First Punic War turned on their masters, Flaubert’s second novel gave him the chance to apply “to antiquity the technique of the modern novel.” This required taking an Olympian view of human slaughter. Flaubert again is nowhere in these scenes of vivid cruelty, unless he is himself the bronze Moloch into whose fiery maw hapless Carthaginians are consigned.

The descriptive power lavished on key scenes in Madame Bovary breaks all bounds in Salammbô. Background overwhelms foreground. As he had done for Saint Anthony, and would do for Bouvard and Pécuchet, his final unfinished novel—“a kind of encyclopedia made into farce”—Flaubert imbibed a whole library, consulting treatises on siege weapons, ancient religions, cannibalism. The atmosphere is perfumed and putrescent, by turns; yet however epic the novel’s action, its total effect is claustrophobic. Flaubert was literally feverish by the end:

The siege of Carthage, which I’m just finishing, has been the end of me. War machines are sawing my back in half, I’m sweating blood, pissing boiling water, shitting catapults and farting slingsmen’s stones. . . . I’ve succeeded in introducing, into the same chapter, a shower of shit and a procession of pederasts. I’ve stopped there. Am I being too sober?

We recall that Emerson thought Whitman “a Minotaur of a man,” and Flaubert, too, was divided, his other half not a rough beast but a connoisseur of beastliness, willing to “immerse [himself] in real life only up to the navel.” Like Hugo, known to Anglophone readers for Les Misérables—which Flaubert deplored—and scarcely at all for his verse epics, Flaubert in English is celebrated mostly for his incisive portrayals of nineteenth-century life, not his hideous set pieces of child sacrifice and crucifixion: “His spongy bones had given under the iron nails, pieces of his limbs had dropped away, and nothing was left on the cross but a shapeless remains, like the fragments of beasts hung at a huntsman’s door.”

He wound up having, in his own time, as George Sand observed, “two publics,” and among the generations that followed a double legacy: one for his social realist novels, in a line of influence falling straight as a plumb line through Émile Zola, Guy de Maupassant, Ernest Hemingway; the other for his works of history and religious fantasy. The latter were chiefly Salammbô and The Temptation of Saint Anthony, which, after years of tremendous research and revision, was finally published in 1874, and which, in early extracts, Baudelaire had recognized as “the secret chamber” of Flaubert’s mind. His house at Croisset had in the previous century been home to a community of Benedictine monks. There, Flaubert dwelled like an anchorite, living out a paradox: only through ascetic habits could he enjoy the voluptuous delights of his writing table.

The savor of those delights, in Salammbô and Saint Anthony, communicated itself to Stéphane Mallarmé (who sent Flaubert a personalized copy of his poem “The Afternoon of a Faun”) and other Symbolists; to the Decadent writers of the fin de siècle; and finally—crossing an ocean—to American writers of weird fiction: H. P. Lovecraft praised Flaubert’s “orgies of poetic phantasy,” Clark Ashton Smith drew inspiration from his work, and Fritz Leiber, without Salammbô, might not have fathered the genre known as sword and sorcery.

Translator Gerard Hopkins judged Flaubert’s novel of the ancient past “a eunuch in the heritage of Western art,” but that was in 1940: Lovecraft was just three years dead, speculative fiction was in its neglected infancy, and it was scarcely possible to see how the Carthaginian clash of arms, together with Flaubert’s overwrought descriptions of faraway places and fantastic peoples, had been answered in the pulp exploits of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Cimmerian. Later lapses are less forgivable. Michael Schmidt’s 1,172-page The Novel: A Biography is utterly silent on this alternative strain of Flaubert’s influence. Nevertheless, it has widened and deepened with time, ramifying into fresh tributaries, a strong precursor to the twenty-first-century New Weird and later works by such authors as China Miéville, with their elaborate world-building and violent action.

Flaubert never stopped yo-yoing between realism and exoticism, Madame Bovary to Salammbô, Sentimental Education to Saint Anthony and beyond. The split concealed perhaps a deeper unity. “I expect nothing more from life but a series of blank pages to scrawl over with black,” he told Sand in 1875. “I feel that I am traversing an endless solitude, going I know not where. And I myself am at one and the same time the desert, the traveler, and the camel.” Not bifurcated, then, but triune—the creator of “a second Nature” indeed.

My life is as flat as the table I write on,” Flaubert declared. We detect a hint of brag. Except for a handful of trips abroad and some schmoozing in high-society Paris (all that ended in 1870, with the outbreak of war), he guarded jealously his placid routine, as he guarded his solitude, the other element indispensable to his work. He liked nothing better than to recline on his green leather sofa or lie in the shade peacefully smoking his pipe.

Yet as the quicksand years whirled him, as age complicated his aversion to life, he grew more interested in the large movements of history, the tectonic grindings of economic systems, class structures, political ideologies, and the arrangements or derangements of social and individual life. Sentimental Education, which draws on Flaubert’s experiences as a law student (redeeming something of that “humiliating” time), has a larger cast and covers a wider ambit of time than Madame Bovary; its politics are more complex. Disturbed by the violent workers’ revolution of 1848—during which Du Camp took a bullet to his right calf—the workingman Dussardier in Flaubert’s novel cries, “The workers are no better than the bourgeois!” In the mature Flaubert, there are flights of ecstatic fancy; yet, even at his most unbound, it is as if a metric ton of mental carbon was crushed to diamond density to make each sentence, to turn each phrase. “Anybody can do as I do—work just as slowly as I, and better,” he wrote. “I am not at all virtuous, but I am consistent. . . . I could have been rich; I said fuck all that, and I continue to live like a Bedouin, in my desert and my pride.”

The disastrous war with Prussia left him, if not rootless, at least uprooted. As many as 40 enemy soldiers were quartered on him at Croisset. He buried a large box of letters and hid his writing notes, and then decamped to Rouen, fuming. Having gleefully heaped up horrors in Salammbô, he found himself appalled by the senseless carnage of “this war for money,” fought by civilized savages. Hate sustained him—hate and Saint Anthony. As before he had written in reaction against bourgeois dreariness, now Flaubert returned to his Desert Father in order to “forget France” amid the bloodletting. This was not insensitivity; it was a refusal to let violence be all. He was an artist, not a war correspondent. “What seems to me the highest and most difficult achievement of Art,” he said, “is not to make us laugh or cry, nor to arouse our lust or rage, but to do what nature does—that is, to set us dreaming.”

Flaubert entered Paris in June 1871, following the French government’s brutal suppression of the Communards at the cost of thousands of Parisian lives. Gone was the Tuileries Palace, where he’d attended imperial balls. The air still stank of corpses. Disgusted, heartsick, and deep in research for Saint Anthony, Flaubert did what he did best: he went to the library. The saint in his drama beholds the passing of the Hindu gods:

Then a great dizziness comes upon the gods. They stagger, fall into convulsions, and vomit forth their existences. Their crowns burst apart; their banners fly away. They tear off their attributes, their sexes, fling over their shoulders the cups from which they quaffed immortality, strangle themselves with their serpents, vanish in smoke.

A cerebral hemorrhage felled Flaubert, aged 58, at his home in Croisset. Among the mourners was Ivan Turgenev, a regular at the Paris literary salons that Flaubert had hosted a few times a year, from 1875 on, as a way of revenging himself on his rural solitude. We hear without shock of Zola, J.-K. Huysmans, the young Henry James, and many lesser lights climbing the five flights to that bachelor apartment, almost a monk’s cell. Parading through Flaubert’s letters are names that defined a century of French literature: Hugo, Gautier, Sainte-Beuve, Sand. In his final months, Flaubert made time (at Turgenev’s urging) to read Tolstoy and found War and Peace “first-rate.” To the end, he refused to stand for election to the French Academy. “What I dream of,” he said, “men cannot give me.” His young protégé Guy de Maupassant wrapped him in his shroud.

Time has dulled our perception of Flaubert’s radical project, which, in its formal elements, has been so thoroughly assimilated as to pass without comment and in its motivating doctrine so widely dismissed as to seem antiquated, even suspect. But the creed of art for art’s sake—deemed irresponsible by the engagé writers of last century—is now a tonic. One need not be an aesthete to deplore the claim today that art is (inevitably, inescapably) political. Wielded by activist-gatekeepers, the statement is not descriptive but prescriptive, a claiming of territory in the guise of naming that territory; moving from is to ought, they implicitly freight that “ought” with an insistence on the right politics, and end by erecting explicit standards that set subject matter above aesthetics, that intrude social messaging into the very act of making. The spirit animating Flaubert’s salons was just the opposite, as James knew: “The only duty of a novel was to be well written; that merit included every other of which it was capable.” Concerned with the moral life, James had his doubts about the doctrine. But how bracing, how liberating it sounds today.

The domain of art is a territory where the exploring is never done. In January 1852, while writing Madame Bovary, Flaubert told Colet, “The finest works are those that contain the least matter; the closer expression comes to thought, the closer language comes to coinciding and merging with it, the finer the result. I believe the future of Art lies in this direction.” Flaubert bushwhacked far in this direction himself—not with a machete but with a scalpel, the family instrument, hence the killing labor it cost him. With his death, it was left to later writers, chiefly Proust, with his nested metaphors, on the winding crystalline staircase of whose prose we seem always to be either ascending to rarer heights of sensation or descending to profounder depths of insight, and Julien Gracq, with his dreamlike narratives of stasis and stalemate, to take literary art still deeper into the territory that Flaubert foresaw.

Top Photo: Gustave Flaubert (1821–80) (PD Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Source link