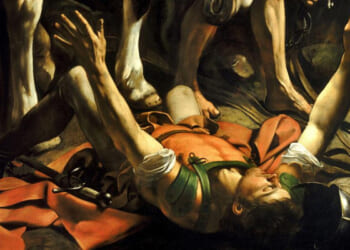

To understand a painting, you start by looking. That is enough. But, of course, there are different contexts in which to consider it. There is the history of all painted images, the local artistic tradition, the most recent movement or contemporary trend, and so on.

One such context is the tradition of Abstract Expressionism, a revolutionary branch of modernism that flourished initially in the mid-1940s and through the 1950s. The movement is also an example of modern art infrequently producing a revolution from within: the avant-garde’s periodic self-succession.

Abstract Expressionist painting contains within it all the advances in the understanding of visual form that developed in modern painting, but it continued on to something new. It also embodies, when the artist permits, the analog par excellence: anti-machine, endlessly sensitive to every subatomic puff of energy and thought, totally unpredictable. It’s antithetical to artificial intelligence.

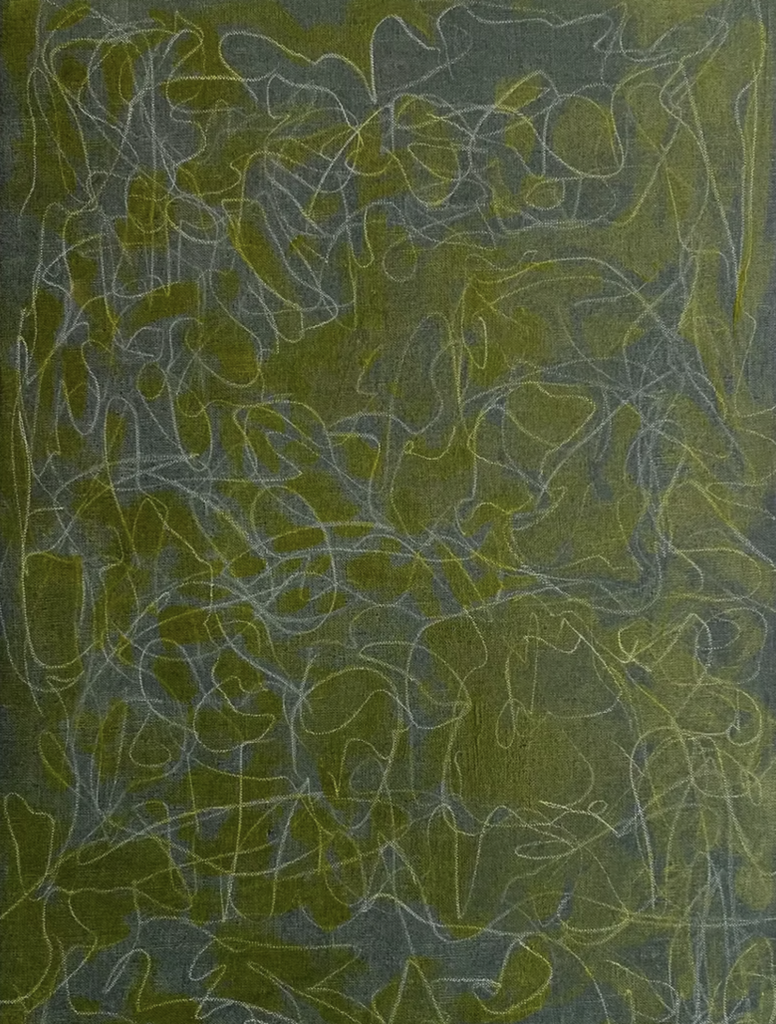

Among the primary traits of Ab Ex is that the arrangement and character of dabs, streaks, and strokes of paint on the canvas—nowadays called mark-making or gestural abstraction—is its primary subject matter as well as its method. The brushstrokes don’t disappear into depictions of people or a scene. The marks are the particles in the field, the molecules in the matter, the strands in the net. Another important trait of the genre is the “allover” structure and composition of the image. There is no main figure separate from its background; the gist of the painting is to be found all over, again like a net. A further source of the mark-making is calligraphy, coming from the preindustrial marks of verbal and pictorial language.

Ab Ex is so powerful that it continues to have many serious adherents today, eighty years after its birth.

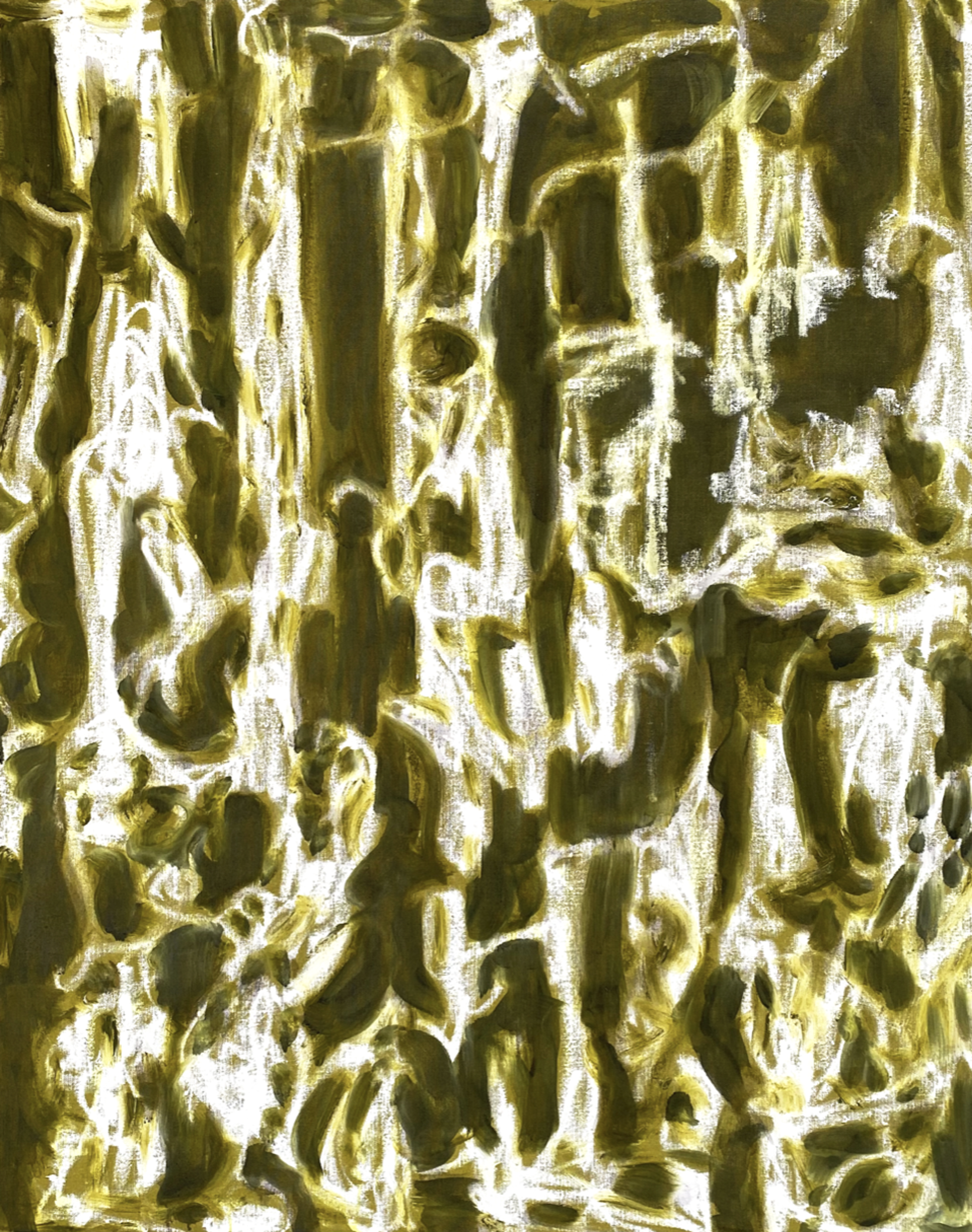

Claire Seidl’s refined, elegant work, now on view in a solo exhibition titled “Days Like These” at Helm Contemporary on New York’s Bowery, identifies her as one of those adherents. And her refined elegance is not just a superficiality. It is replete with inventiveness and a soothing, deeply satisfying engagement, one that conveys the artist’s pensive sensibility. For Seidl, Ab Ex methods are a language both personal and universal.

Variations on marks characterize her works. Each painting, set in its own atmosphere of restrained color that often conjures a heightened mood, has its own type of mark. To explore the offering of the canvas, the artist uses the free, expressive line that runs through all of art history.

Enough About Me (2023) is the masterwork of the show. The brilliant brushstrokes, both forceful and subtle, bring out a world of incipient calligraphy, lurking with meaning, on a ground of multicolored earth tones. Tout Est Clair (2022) is at first like a loose network of lightning flashes or inescapable northern lights, trenchantly drawn. When you get closer, the painting’s dark ground becomes the main act, made up of the greenish negative shapes of the light streaks. Days Like This (2024) includes several layers of loose drawing. The top layer appears soft and made of light. Drum Roll (2022) is small and delicately marked, enticing you to come close and notice the weave of the canvas, which suggests that this, like Seidl’s other paintings, is a loose, personally felt drawing on a surface. The surface may be as important as the marks.

These recent paintings are evidence that Ab Ex was not just a period style. The potent influence of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning ought to be seen as even more enormous and complex than it has been so far.

But one aspect of Ab Ex missing today is the revolutionary—but infrequent—innovation of the avant-garde. Not the familiar rejectionism of the pseudo-avant-garde, the silly “transgressions” and academic carping of intervening decades, the endless variations, or the feckless mockery, but the novel creation that is based in the great achievement of the past and makes something astonishing out of it. Such an innovation is truly sensational, as when Van Gogh’s and Cézanne’s work first appeared, or when Picasso inaugurated Cubism, or when Pollock and de Kooning and their cohort achieved the same with Ab Ex in the late 1940s. This kind of achievement isn’t recognized right away.

Art history is deep and long, and to understand it sufficiently seems to take even longer in our knowledge-filled era. Perhaps it takes artists who have been at it for a while, like Seidl, to find a way through the long tradition to a real new thing.

Seidl is a serious photographer as well as painter. Only one of her unusual photographs is in this show, which concentrates on her recent paintings. Many of her photos have strange streaks and flashes of light, apparently emerging from the scene and the moments of the image’s creation. The photos may contain hints of the paintings’ patterned space, and some of the paintings likewise share in the photos’ glow of light. But the photos are dominated by unexpected blasts of light, not an allover composition. Bringing this kind of surprise into the paintings might disturb their comfort.

Ab Ex was the last major art movement to come into being unspoiled and unbidden by market and academic forces. A few loyal and enthusiastic collectors and artists discovered it. At the time, the New York art scene was tiny, and there wasn’t anything you’d recognize as a market for contemporary art. Perhaps this authentic beginning helps to keep the genre fecund territory for the new and truthful.