A decade ago, the ground floor of Prague’s Savarin Palace was a McDonald’s, sweating a miasmic haze of beef emissions into those Late Baroque curves. This ancient city deserves better. The palace looks out on Na Příkopě street, a five-minute walk from Wenceslas Square. Today, these are typical European shopping streets, where punters can see and buy and feel the same things as anywhere else. But Wenceslas Square is where, two weeks before the World War I armistice, Czechoslovakia declared independence from Austria-Hungary; where, in 1969, the student Jan Palach set himself on fire protesting the previous year’s Soviet invasion; and where, three decades later, cheering throngs saw communism fall. Turn in the other direction and, within a few hundred feet, there’s the neoclassical Estates Theatre, where Mozart premiered Don Giovanni two and a half centuries ago. Now the palace houses a new museum dedicated to Alphonse Mucha, an artist better known for his style than by name.

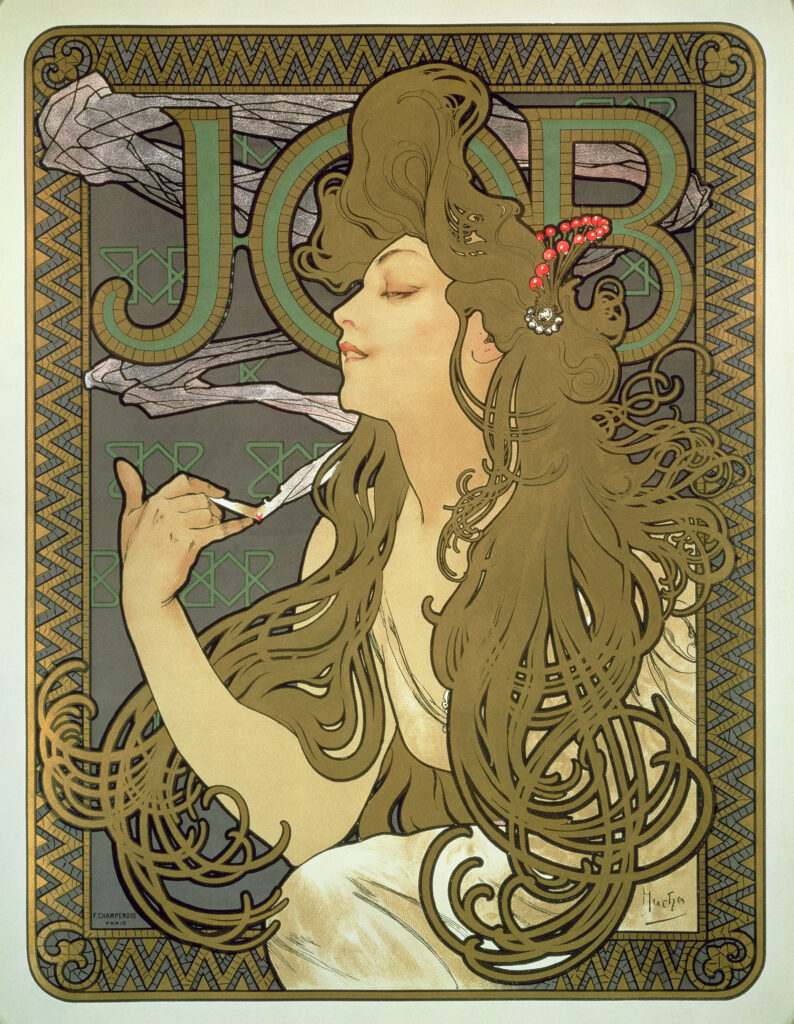

The average consumer may recognize le style Mucha: posters advertising perfume, cigarettes, alcoholic drinks, chocolate, and cookies, the products displayed by women in sensual gowns radiating languid delight. A JOB cigarette paper advertisement from 1896, for example, shows one such beauty enjoying a smoke, eyes closed in quiet rapture, haloed by the O in the company logo while coiling fumes waltz with her hair. Mucha’s Chocolat Idéal poster from 1897 has a mother, beaming serenely like a bringer of liberty and light, presenting her two children, all itchy with anticipation and clawing like kittens at her dress, with cups of steaming hot chocolate.

Such lithographs, printed by the Parisian publisher F. Champenois in the late 1890s, remain Mucha’s most famous works. But the new museum reminds us that they are only part of his output. “Art Nouveau & Utopia” displays ninety original works spanning his career, from his student days at the Munich Academy in the mid-1880s to his final years just before World War II.

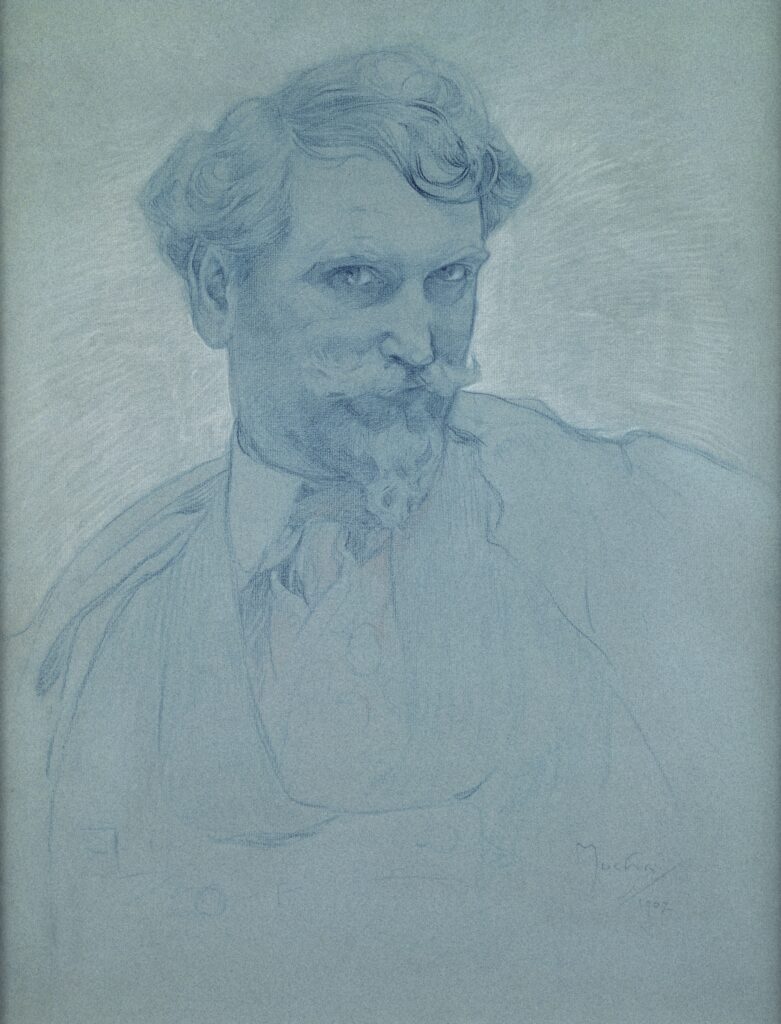

The permanent installation begins with Study of a Male Nude (ca. 1885–87), in which the young man’s classical pose and naturalistic modeling reflect the academic realism taught in Munich, then a European center of rigorous draftsmanship. Also included are six posters made between 1894 and 1899 for productions at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Paris, showing Sarah Bernhardt, then the world’s most famous actress, nobly posing as a doomed lover in Tosca, a vengeful sorceress in Medea, and a tormented prince in Hamlet. Further posters, some better known than others, depict allegories of the arts, seasons, flowers, and celestial bodies. Explanatory panels stress Mucha’s linework and use of Czech folk motifs.

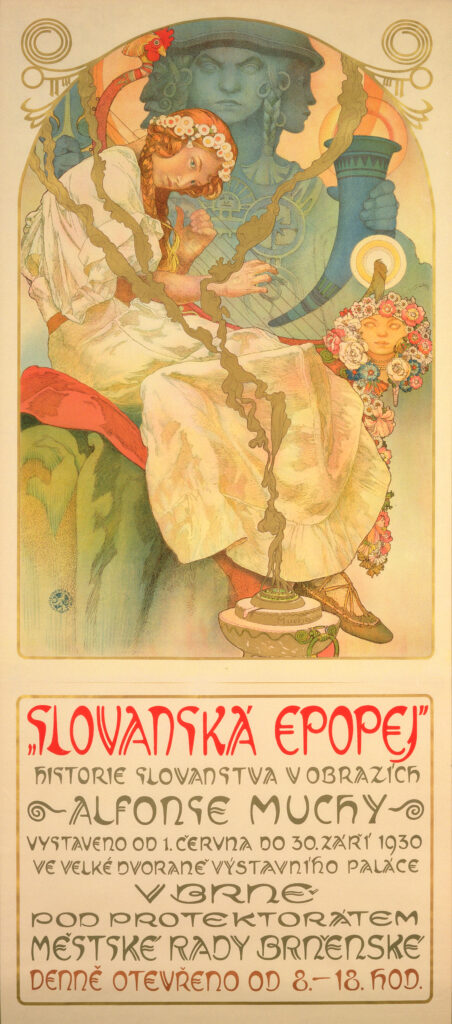

They also hint at Mucha’s eccentric, solemnly held, but now deeply unfashionable beliefs: nondenominational Christianity, pacifist humanism, Czech romantic nationalism, and fascination with the occult, this last interest developing after Mucha met August Strindberg in 1894, studied parapsychology with Albert de Rochas, and became active in Freemasonry. The artist’s “spiritual” sensibility surfaces in Le Pater (1899), an illustrated edition of the Lord’s Prayer, and the enormously ambitious Slav Epic series (1910–28).

A painting cycle of twenty monumental canvases, the Slav Epic presents an idealized vision of Slavic history—Mucha’s personal take on the era’s pan-Slavism—from the Dark Ages to national revival, culminating with Apotheosis: Slavs for Humanity (1926), a utopian future of universal brotherhood, featuring a Christlike figure, with outstretched arms holding two floral garlands, who oversees people of different nations marching together as one, though still under their own banners, hailed by adoring crowds. The series’ incantatory tone is especially evident in the beatific Holy Mount Athos: Vatican of Orthodox Christianity, Sheltering the Oldest Orthodox Literary Treasures (1926), in which a procession of pilgrims tremble before four high priests bearing relics and a ceiling mural of the Virgin as sunlight streaks through the sanctuary, nine angels surveying all.

Mucha’s posters channeled his academic training—the naturalistic modeling seen in the early nude—into commercially appealing ends. The pleasure on the faces of his comely dreamers reappears in Holy Mount Athos as something eerier in the angels, probably informed by his spiritualism: not just an air of ethereality, but luminous, blue-green skin.

The work was hidden from the Nazis as they stomped into Czechoslovakia in March 1939. Mucha’s views were well-known, and he was one of the Gestapo’s earliest arrests. By then, Mucha was seventy-eight years old, and his health was destroyed by the interrogation; he died a few months later. To the Nazis, Mucha was a “degenerate,” but to the Communists, he was bourgeoisto boot and erased from “official” cultural history.

Under Communism—democratically elected in 1946, installed by coup d’etat in 1948, and reimposed by chummy Soviet tanks offering “fraternal aid” twenty years later—admirers struggled to preserve the Slav Epic along with Mucha’s legacy. During the “normalization” period after 1968, during which the regime crushed and humiliated all opponents, museum and university positions went only to vocal Party loyalists. During this time, Mucha had just one major solo retrospective, at Prague’s National Gallery in 1980, and there was no memorial plaque for the artist anywhere in the Czech capital, though his reputation flourished abroad, despite neglect by academic art historians. Since 1963, the Slav Epic has been displayed at a castle in Moravský Krumlov, a small town near his birthplace, seventeen miles southwest of second-city Brno, where it has remained until today.

Even so, it has yet to be installed in the new Mucha Museum. For now, visitors can only view scale reproductions of five of the works in the cycle. The museum occupies the first floor of the Savarin Palace, but with only about five thousand square feet, it feels slight given Mucha’s ambitions and the size of the collection (at least seven thousand items, according to the Mucha Foundation). The museum itself is a work in progress, part of a broader effort to turn the palace into a “cultural hub” with shops and restaurants, perhaps in homage to its interwar halcyon as a popular social club and café, presumably aimed this time not at surrealist revolutionaries or gloomy dissidents but at chattering young Praguers merrily chomping down gourmet burgers and fries.

Still, the museum rights some art-historical wrongs. Mucha’s name is so deeply associated with the elegance of fin-de-siècle Paris that he is often mistaken for a French artist, obscuring his nationalism. Ironically, the prominence of his national identity in his work explains his neglect inpre-communist Czechoslovakia, when modernists found his idealized patriotism passé, as well as during normalization. He in fact rejected the very decorative art that made him so famous to do “work for the nation” with an eye to world peace; moreover, he only began designing posters to make money after losing the patronage of the Tyrolean count Eduard Khuen-Belasi in 1889.

That Mucha’s style reappeared in the 1960s as a psychedelic cliché—the default aesthetic for cheap one-way tickets to Xanadu across Europe—only insults his legacy further. Yet even if the new museum is incomplete, it marks a long-overdue reckoning with Mucha’s legacy. If his ambition was to create art for the nation, at least now the nation will see him again, whatever they make of his fevered imaginings.