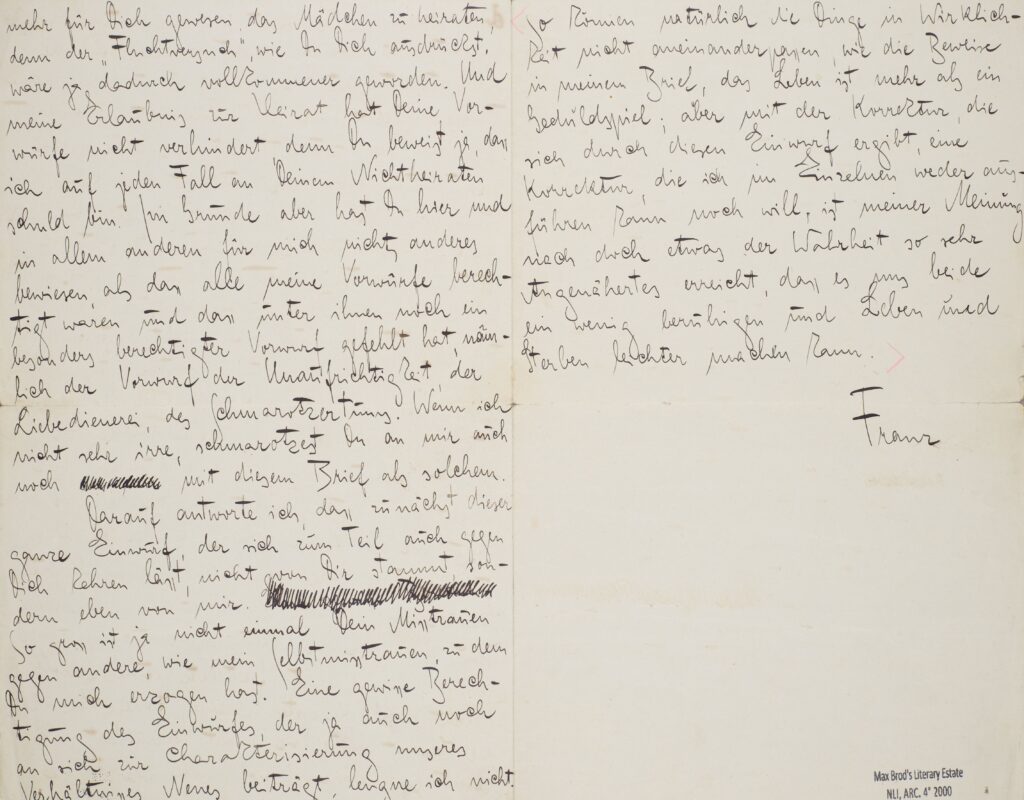

Franz Kafka published little during his life and shared the manuscripts of his novels and short stories mostly with confidants in his literary “Prague Circle.” After contracting tuberculosis, Kafka burdened his closest friend, Max Brod, with destroying his writings after his death. When Kafka died in 1924, he left Brod a letter reiterating his wishes: “Everything in my estate . . . including diaries, manuscripts, letters from others, and myself, drawings, etc., should be burned without exception and without their being read.” Brod ignored the request and instead consolidated Kafka’s literary estate for posterity and published Kafka’s now-famous novels The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika.

The contents of Kafka’s estate are on view for the first time in the exhibition “Kafka: Metamorphosis of an Author,”currently at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem (the opening of which I wrote about in November 2023). With Brod’s famous letter on display, Kafka’s last wishes haunt the exhibition as his original manuscripts, letters, photographs, and diary entries become windows into a personal and literary world that was never intended to be seen.

Two questions frame the exhibition. Can Kafka be considered a Jewish writer, and can his literary estate be regarded as Jewish national property? Rather than resolve these questions with firm claims, the exhibition weaves through a labyrinth of artifacts as clues and threads a narrative that challenges viewers to reach their own conclusions.

As in most assimilated European Jewish families in the early twentieth century, Judaism played no role in the Kafka household. Aside from the one page that mentions a synagogue in his forty-seven-page “Letter to His Father” from 1919, there are no Jewish characters or themes in Kafka’s literary corpus. While his writing may lack religious connections, the exhibition explores how, by 1912, Kafka began to show a personal interest in the cultural aspects of Judaism. The manuscript of a lecture Kafka gave that year on the essence of Yiddish is a testament to his passion for the language and his intent to foster interest among assimilated peers.

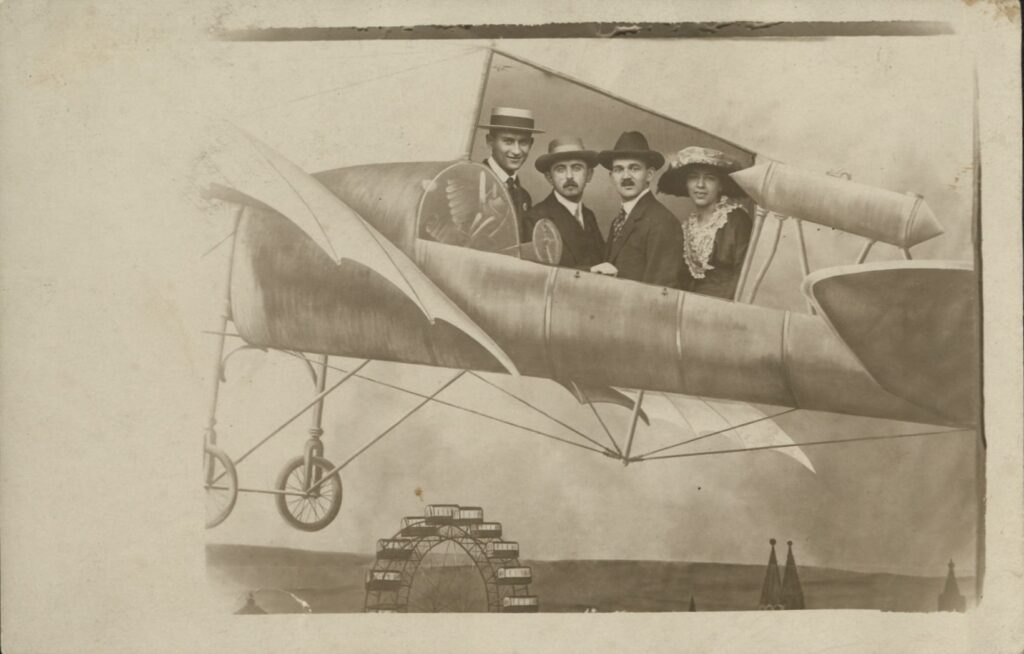

Kafka’s attendance of and reaction to the Eleventh Zionist Congress in Vienna in 1913 only further complicates his Jewish identity. He described in a letter to Brod how the congress was “a completely foreign event” and confessed that he was “quite miserable” and entertained himself in the audience by throwing paper balls at other delegates. He did manage to make new friends at the congress, as a photograph shows him with the poets Albert Ehrenstein and Otto Pick and his friend Lise Weltsch at Vienna’s Prater Amusement Park—a rare record of Kafka smiling.

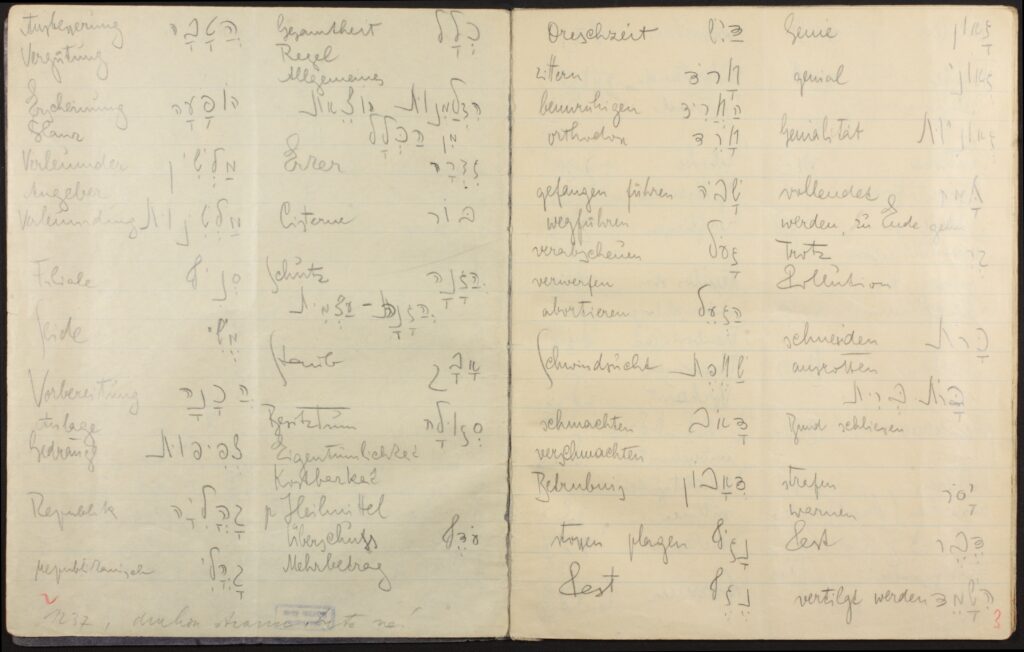

His negative assessment of the congress perhaps confirms his maxim, “If it is not literary, it bores me,” more than it affirms any pejorative thoughts he may have had about Zionism. By 1917, Kafka had taken an interest in Hasidism and the Hebrew language, and his notebooks included legible sentences in modern Hebrew and a page dedicated to “antique” words collected from the Tanakh.

His intellectual and social circles also consisted mostly of assimilated Jews and Zionists, as did his early critics. Gershom Scholem’s “Note on The Trial by Kafka,” from 1926, is perhaps the first critical article to identify Kafka’s literary depth. Scholem’s friend Walter Benjamin later marked the tenth anniversary of Kafka’s death with an essay expounding upon his literary innovation and quoting at length from most of Kafka’s books. The wall text accompanying the photographs and letters from Vienna noted: “Kafka’s close friend Brod and others were convinced that Kafka was a Zionist because he had considered immigrating to Eretz Israel but was prevented by his poor health.”

While Kafka never made it to Eretz Israel, his literary estate eventually did. Brod caught the last train out of Prague before the Nazis closed the Czech border in 1939, saving Kafka’s manuscripts from the hands of Nazis, who, in a grim coincidence, were likely to carry out Kafka’s wishes by burning them. Brod settled in Tel Aviv and received an offer from Salman Schocken to house Kafka’s literary estate in the basement of his exclusive Erich Mendelsohn–designed library in Jerusalem. Schocken had Kafka’s manuscripts translated into Hebrew, and, over the following decades, his writings received renewed appreciation and criticism from the first generation of Israeli literary scholars.

The exhibition’s final gallery attempts to untangle the controversial litigation over the NLI’s possession of Kafka’s estate. Brod died in 1968, and his legal will appointed his secretary, Ilse Hoffe, as the heiress to his property, including the Kafka papers. Brod additionally requested that upon Hoffe’s death, his and Kafka’s estates should be given to either the Jewish National and University Library (today the NLI), the Tel Aviv municipal library, or a public archive in Israel or abroad if no other arrangements had been made.

When Hoffe began selling Kafka’s material overseas for profit, the State of Israel took her to court, fearing that Kafka’s estate would soon be lost. The Tel Aviv district court, however, ruled that Hoffe was entitled to do as she wished “during her lifetime,” and Brod’s “request” only applied to material left in Israel after her death.

The issue returned to court when Kafka’s estate passed to Hoffe’s daughter, Eva. The NLI argued that Brod’s request regarded Kafka’s estate as “Jewish national property,” while Eva stood firm in her defense that Kafka was a “universal” writer who never lived in Israel or dealt with Jewish themes. The matter was finally resolved in 2016 after three court decisions in Israel and others in Germany and Switzerland ruled in favor of the NLI. “Brod did not want his estate, and everything in it, to be sold to the highest bidder, but to find its appropriate place in the literary and cultural sanctuary that was his life’s work,” the Israeli Supreme Court decided.

The NLI now holds the third-largest portion of Kafka’s estate, after Oxford’s Bodleian Library and the German Literature Archives in Marbach. While the exhibition claims no verdict on the questions it poses, it does celebrate the fact that, one hundred years after Kafka’s death, the great cultural value of his life’s work has been preserved and continues to live on.