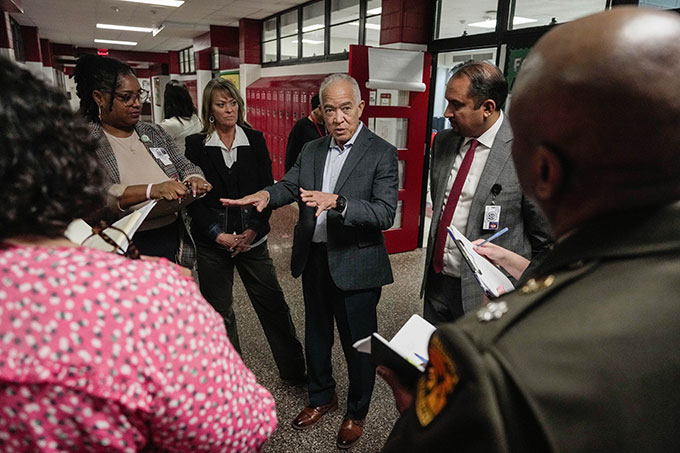

In 2022, only about one in five students in Houston could read or do math at grade level. Mike Miles, the recently installed superintendent of the Houston Independent School District, is on a mission to improve this dismal performance. His methods—a combination of traditional education, discipline, and careful monitoring and data analysis—might hold the key for success at other struggling urban schools.

The Texas Education Agency appointed Miles to lead the Houston ISD in 2023 as part of a state takeover that saw the district’s elected school board replaced by an appointed board of managers. The agency took this drastic step to address the district’s longstanding poor performance—more than 120 of the district’s 274 schools had D and F ratings, according to the Texas Education Agency.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Under Miles’s leadership, student performance is turning around. Federal data released in 2025 show that Houston stopped the pandemic-era learning loss in both reading and math—an astonishing achievement among urban school districts. For the 2023–2024 school year, Houston schools with the poorest students saw the largest single-year improvements in district history on state exams. The nonprofit Children at Risk also found in its annual survey that Houston ISD schools with disadvantaged student bodies showed significant improvement since Miles’s takeover.

What’s behind these success stories? Not the latest trendy educational interventions. Rather, as Miles has said, he is engaging in “comprehensive reforms done all at one time” through the district’s New Education System (NES). Under Miles, the district now categorizes the worst-performing schools—130 currently fall under this designation—as NES schools, which then receive intensive reforms to their curricular and institutional practices.

NES status brings a host of changes. Teachers get higher salaries at NES schools than at non-NES schools: $80,000 vs. $65,000. To accommodate working parents, NES schools stay open longer than non-NES schools. The better pay for teachers, along with spending on special education support, means that per-pupil spending at NES schools is $2,500 more than at non-NES schools.

But spending alone isn’t driving the improvement. The NES curriculum uses Direct Instruction, a teaching method created by education researcher Siegfried Engelmann in the 1960s. In DI, the teacher stands in front of the class and takes an active role in guiding student learning, strictly following a set curriculum. The method is considered controversial in education circles, with critics viewing it as authoritarian. The education establishment typically promotes “student-centric” learning, which puts students in the driver’s seat of their own instruction.

But “students cannot guide their own learning when they cannot read,” as Miles told me, or “just do what they’re interested in when they’re way behind in math.” Indeed, research shows DI is the best teaching model for at-risk kids.

Under NES, classes in core subjects are 90 minutes and follow a strict structure. Students receive instruction for 40 to 45 minutes, followed by a ten-minute mini-quiz to measure what they’ve absorbed. Based on the results, students are then separated into one of several categories for the second half of class: Learner (L), Securing/Secured (S), Accelerated (A), and Enriched (E). Students in L and S need extra help to understand that day’s objective, while those in A and E can work independently.

Many districts around the country have dismantled gifted programs for “equity” reasons. Houston’s NES schools, by contrast, try to help both struggling and proficient students to make educational gains. “All kids need to be challenged, and all kids need to improve from where they are,” Miles said.

NES schools also adopt a no-nonsense approach to disorder and violence. This attitude toward school discipline may also help students focus on learning. For the kinds of lower-level infractions that contribute to disorderly classrooms, such as bullying or throwing items, students are sent to a separate room, where they must attend class remotely via Zoom, under close adult supervision. “Kids hate that,” Miles said, calling it “time out with a study.” Students can return to class with the rest of their peers only after the class period is over.

It seems to be working: discipline for fighting and code violations declined by 15 percent to 20 percent at NES schools between the 2022–23 and 2023–24 school years, even as it rose at non-NES schools by a similar percentage. Achieving these improvements required removing some of the worst offenders from classrooms. NES schools saw a larger increase in referrals to alternative education programs for serious infractions than non-NES schools.

The kinds of changes Miles is pursuing are not easy to implement. Some parents worry about over-testing and burnout. Some teachers feel confined by the strictures of the curriculum. But Miles says large-scale reforms are needed to transform urban education.

“The reason why we as a profession haven’t been able to move the needle much is that we continue to do piecemeal incremental reform,” Miles said. “In the profession, if you try to do one thing, the entire system pushes back . . . and then you get a watered-down program or intervention.”

Houston ISD still has a long way to go to ensure that students meet state and national standards. But its new leadership is showing that “old-fashioned” education practices haven’t gone out of style.

Top Photo: Yi-Chin Lee/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link