When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines, by Graydon Carter (Penguin Press, 422 pp., $32)

In a 1974 Paris Review interview, an elderly Archibald MacLeish was asked about “the special pull of the Murphys,” the couple, Gerald and Sara, who personified the 1920s literary scene of American expatriates in Paris. “There was a shine to life wherever they were . . . a kind of revelation of inherent loveliness as though custom and habit had been wiped away and the thing itself was, for an instant, seen,” MacLeish said. “Don’t ask me how.”

That same elusive quality could describe Vanity Fair and its writers in the 1990s and 2000s. Graydon Carter, as editor from 1992 to 2017, was the conductor of the orchestra. “You never know when you’re in a golden age. You only realize it was a golden age when it’s gone,” Carter writes in his new memoir, When the Going Was Good.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Carter’s reminiscences and life lessons—rooted in serendipity but also failure— “Few people learn from success. A worthwhile professional life is built over a boneyard of failures”—are drawn from an analog past, when baby boomers like himself cut a circuitous path to reinvention and prosperity. Carter’s memoir, in part, is an elegy for a time devoid of algorithms and pixels and instead more tailored, smoke-filled, and ink- stained. Think a noir film or screwball comedy rather than a frenetic Instagram reel or angry X post. In a less fragmented media culture, magazines were the ultimate curators. As Dana Brown, Carter’s deputy editor at Vanity Fair, recounts in his own memoir, Dilettante, glossy magazines and celebrity editors like Carter “were the arbiters of taste, the translators of culture . . . They decided what was cool, what was important, what was necessary, what made it onto their pages, what people would be talking about, watching, reading, wearing, thinking.”

Advertisers played a major part in funding all this influence and glamour. In the case of Vanity Fair, advertisers—such as the period’s leading fashion designers—spent upward of $100,000 for a single page in the hefty magazine. Ad dollars, in turn, funded livelihoods that glittered with perks for editors and writers. At one point, Carter discovered a half dozen staff members waiting in line for “the eyebrow lady,” considered “the best in the city,” who, it turns out, visited the office monthly for decades. “This, in its essence, was Vanity Fair,” Carter writes. “Younger people would never understand the expense-account stories of the time, because that all disappeared with the Great Recession, in 2008.”

Before the Concorde flights and Oscar parties, and long before that modern economic crash, Carter, the son of a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot and an artistic mother in frigid Ottawa, dreamed of the glamorous life. He’d spend hours studying old periodicals at the public library or pull a Ferris Bueller and stay home from school to devour films and magazines, his portals to a desired “adult life of cocktails, cigarettes, bridge games, witty banter, and clothes that weren’t tartan.” These remained daydreams after high school, when Carter worked briefly as a railroad lineman. Soon, signs of a more promising future emerged. After two short-lived forays into college in Ottawa, he helped launch a new magazine called The Canadian Review in the mid-1970s. And so began this editor’s working life.

Though The Canadian Review boasted a robust circulation—“fifty thousand, which was enormous in a country a tenth the size of the United States”—the money ran out quickly. As Carter recounts, the failure taught him, “Whatever you do, it has to have a point.” The magazine was neither “liberal nor conservative, it was part politics, part literary criticism, part sports, part arts. It didn’t have a point beyond the fact that it was a magazine and I got to edit it.”

With a thin and unpromising resume, Carter struggled to find work before serendipity struck: he was introduced to Ray Cave, Time’s top editor, who responded to his plea for a job. To a young Canadian like Carter in the late 1970s, magazines told the story of New York, of “its industry, its might, and the people who made it the center of just about everything I was interested in.” Magazine offices filled skyscrapers in midtown and uptown Manhattan. Carter moved to New York, and though he didn’t find long-term success in his “floater” writing position at Time, he cultivated colleagues who would prove lifelong friends. After Time, Carter did stints at a short-lived Westchester County weekly that competed with TV Guide and the fading Life before starting a “new magazine [that] would have a point”: Spy.

Launching in 1986, Spy skewered New York’s elite with a style suggesting “bemused detachment” but also somehow “witheringly judgmental.” As Carter recounts, “We wrote about and lampooned everybody who was part of New York’s social and professional life, and circulation soared.” By the early 1990s, Carter had left Spy and was running The New York Observer, an established but lifeless, salmon-colored newspaper that he transformed into a fun, newsy read that covered “the doings of the characters who made up the city’s business and nightlife.” The newspaper caught the eye of Condé Nast chairman Si Newhouse, who mistakenly thought it was a global success when he saw it abroad. Newhouse invited Carter for a meeting at his UN Plaza apartment, where he offered him the editorship of either The New Yorker or Vanity Fair. Newhouse had been busy boosting Vanity Fair since 1983, when he resurrected the long-defunct publication—a Jazz Age chronicler in its first incarnation, before folding in 1936—with the goal of turning it into a New Yorker with pictures. By the late 1980s, under editor Tina Brown, the magazine was on an upward trajectory. Carter, mindful of Spy’s satirizing of the Vanity Fair crowd, chose The New Yorker. Two weeks later, though, his dream slipped away: Brown got the editorship when, “at the last moment [she] insisted on moving to The New Yorker, and Si had agreed.” Carter would run Vanity Fair. “I thought, Oh fuck,” he writes.

Despite the stress and uncertainty of Carter’s new gig, he recounts how, “Going from Spy and The Observer to Vanity Fair was like moving from a youth hostel to a five-star hotel.” Carter viewed himself initially as a “wobbly steward” of Vanity Fair, but overseeing a magazine with “punishingly expensive journalistic costs” partly covered by advertisers, he focused his attention on serving readers. With time, “I had a pretty decent idea of what they were looking for . . . A tasteful but arresting cover that they could leave on the coffee table without too much embarrassment.” It was a magazine that covered Wall Street and Silicon Valley, reported on scandals everywhere from the art world to Hollywood, reflected on history and literature and politics—all with a distinctive elegance. “Assembling an issue of Vanity Fair was like producing a movie each month,” writes Carter. “We wanted to make each new issue feel like an event.”

Carter details the fresh ideas—its Oscar party, its New Establishment Summits, its annual Hollywood cover—that turned Vanity Fair into a singular cultural force. A Vanity Fair cover, often shot by photographer Annie Leibowitz, could become its own news cycle, as was the case in 2006, when she took the cover photo of Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes’s baby. “Looking back at it now, I honestly find it difficult to understand what all the fuss was about,” Carter writes.

The book’s often memorable passages span the personal—the mechanics, often dreary and monastic, of being an editor; his preference for a quiet home life with his family—to Carter’s recollections of building a roster of age-defining writers and editors. The writers possessed many talents but were never short on idiosyncrasies, and Carter and the other editors faced constant pressure to guide them, with generous expense accounts, toward workable drafts that became enduring works of narrative journalism.

Among Carter’s most vivid profiles is Christopher Hitchens, his first writing hire at Vanity Fair. Hitchens’s “well-calibrated but unflagging intake of alcohol and nicotine produced nothing but swift and faultless prose, even after lunches or dinners where others would be hors de combat,” writes Carter. Hitchens, later a contributor to City Journal, distinguished himself as a contrarian and one of the last true public intellectuals, becoming a nightly fixture on cable news shows like Hardball with Chris Matthews.

Carter did not hire but inherited another writer, Dominick Dunne, whose true-crime stories, covering everything from the Menendez Brothers to the O. J. Simpson trials, dominated news headlines. Dunne, he says, was “the only reporter on staff who wasn’t objective in approaching his reporting”—likely because his own whose daughter had been strangled to death by her ex-boyfriend, leading to a high-profile trial of its own in 1983. “Because of what had happened to his daughter, he came into a story from his own moral perspective: writing from the point of view of the victim.”

When Vanity Fair took off under Carter, “cyberspace” was a novelty and magazines still reigned. In the mid-nineties, “All the young talent of the moment was eschewing other industries and flocking to the business,” wrote Dana Brown in his Vanity Fair-focused memoir. “It was the coolest place to be. The center of the media and cultural universe.” As late as 2005, Carter still didn’t have a cell phone, and it was his wife who told him on their Bahamas honeymoon that Vanity Fair was about to publish the article revealing the identity of the Watergate scandal’s “Deep Throat.” Soon enough, though, pixels and shifting economics were making their encroachments. The business, “brutalized not just by the great recession of 2008 but also by the relentless appetite of the internet, was in the beginning of a period of rapid decline,” writes Carter. In 2017, amid corporate flux and tensions with Condé Nast editorial director and Vogue editor Anna Wintour, Carter left Vanity Fair. Today, he’s co-editor of Air Mail, a digital weekly creation that captures the spirit of the magazine age with narrative journalism, cultural pieces, and international reporting.

“Time,” Jonas Mekas, the late filmmaker, once wrote, “turns everything to dust—paintings, stones, pyramids. Films fade, frescoes fall off the walls, polluted rains eat up the architecture . . . What survives, survives only through a mysterious act of grace, and even so only temporarily.” When the Going Was Good gracefully documents what one magazine did in a unique period that lingers in American cultural memory as a time of balanced technology and comparative innocence. In the basement of my childhood home, a large cardboard box holds all the Vanity Fair issues that I read during high school and college in the 2000s. In just a single issue, such as August 2007, you can find everything from David Halberstam’s final feature and Dunne’s coverage of the Phil Spector murder trial to an historical essay on Gerald and Sara Murphy, the Jazz Age’s “it” couple. As these old editions and Graydon Carter’s memoir show, readers weren’t just imagining the magic.

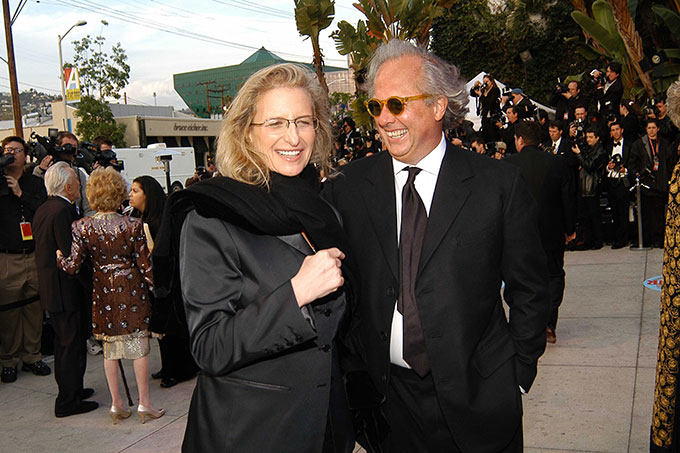

Top Photo: Graydon Carter in 2017, at the Vanity Fair New Establishment Summit (Photo by Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images Entertainment via Getty Images)

Source link