A Town Without Time: Gay Talese’s New York, by Gay Talese, introduction by Alex Vadukul (Mariner Books Classics, 432 pp., $29.99)

Any proper biography of Gay Talese would also be a history of modern American journalism, if only incidentally. Talese, now 93, started in the field as a teenager, publishing hundreds of columns in his hometown paper, New Jersey’s Ocean City Sentinel-Ledger, before he turned 18. In the decades since, he has been a New York Times reporter, a magazine writer, and the author of several best-selling books, including Honor Thy Father (1971) and Thy Neighbor’s Wife (1981), based on his immersive reporting. He has been a close observer of journalism’s power struggles and cultural shifts, most notably in The Kingdom and the Power (1969), his book about the New York Times. He has also been famous himself for much of this time, which has given him the dubious honor of having journalism practiced upon him in turn.

In his introduction to a new collection of Talese’s writing, A Town Without Time: Gay Talese’s New York, Alex Vadukul argues for Talese as “one of the great chroniclers of New York, worthy of a place as a spiritual contemporary to Joseph Mitchell.” Talese has called the city home since 1955, and he has profiled New Yorkers of all kinds, from the humble, eccentric, and even pathetic to entertainers and leading media figures. He has spoken of his technique as “the art of hanging out.” He stays until you forget he is there. He cultivates trust. His loyalty to his subjects and sources is absolute. New York changes constantly and without regard for the memories, preferences, and cathexes of its inhabitants. Meanwhile, Talese does his patient work, giving the city back to us without judgment and without sentiment.

Though his subjects are often celebrated people, Talese’s New York is a deglamorized city. Desperation and loneliness are never far from the surface. Bill Bonanno, the Mafia scion of Honor Thy Father, is not a friendless man, but his position as the boss’s son simultaneously protects, endangers, and isolates him. Likewise the senior Times editors profiled in The Kingdom and The Power. Theirs is a gregarious profession, and the publication of a daily newspaper is a communal endeavor. Yet they are isolated, too, by their institutional role, which requires keeping supplicants at a distance, and by their ambition, “whose precise nature must be kept secret.” Joe DiMaggio, the subject of Talese’s “The Silent Season of a Hero” (1966) (not included in A Town Without Time), was a desperately lonely man, made so by his truculent nature and the inescapable pressure of his fame. That innermost person, who has only himself for companionship, is the one for whom Talese is always waiting to emerge.

Talese’s world is largely male, and his subjects enjoy lives rich with masculine prerogatives but also cabined by tight masculine behavioral codes. In the celebrated “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” (1966), a scene unfolds in which Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Joey Bishop watch the insult comic, Don Rickles, perform in Las Vegas. Rickles subjects them to sharp abuse (“Joey Bishop keeps checking with Frank to see what’s funny”), which they accept good-naturedly and as a form of tribute. All this jocularity comes with a certain amount of strain for the reader, however, because at every moment, the complex, shared understanding among the performers is in danger of breaking down.

Talese’s work is interesting to read at a cultural moment when many men, purportedly liberated from stifling gender norms, are restless in their liberation and fascinated by subcultures—elite military units, combat sports—to which intensely demanding behavioral codes are essential. To be a man without such a code, they feel, is to risk non-being. The Mafia’s omerta has lately been revealed to be something less than inviolable. One can’t help but notice, however, how little Bill Bonanno, who confronts the likelihood of violent death from the first page of Honor Thy Father, complains about his dire circumstances.

Talese sees Bonanno as an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances. “He had not seen [his wife] or his four children in several days,” he writes, as though speaking of a traveling salesman, “and he wondered about their welfare and wished that his relationship with his in-laws, the Profacis, had not declined as it had in recent years.” Bonanno is perhaps more guarded than other people, by necessity more meticulous in his business arrangements. Otherwise his life seems largely to be one of ordinary pleasures and sorrows. He is married to a pretty and conventional woman raised in the same social circle. Even his position as an organized crime figure is a signature of his ordinariness: he went into the business his father built. Talese is not quite claiming, I think, that because Bonanno’s inner world is ordinary, his life is blameless. Over 500 pages, however, our assumptions about Bonanno recede, and our attitude merges more and more with Talese’s radically nonjudgmental ethos.

Talese had to invent a new form of celebrity journalism for the Sinatra piece, because his subject wouldn’t talk to him. One imagines the meetings between Sinatra and Talese that never took place. Sinatra was, at that time, among the most famous entertainers in the world. Talese himself was not without what Freudians call “transference valence”; he was already a journalist of some prominence, well-connected in the literary and publishing world. Would Sinatra have tried to intimidate Talese—bully him with silence, win him over with some generous gesture? In a sense, these two Italian-American sons of New Jersey were made for one another. Both were small men of great physical charisma. They had the immigrant son’s hunger for success. They also shared a creative rigor and passion that, in the “wee small hours,” must have seemed the precise opposite of glamorous. Perhaps they would have repelled one another, like magnets. We will never know, because Sinatra caught a cold.

Much of Talese’s best writing is about people who take themselves very seriously, people of drive and ambition who may, like Sinatra and DiMaggio, be capable of cruelty in the service of their desires. (“[I]t was a bad idea to force conversation on [Sinatra] when he was in this mood of sullen silence.”) He does not ask that his subjects be humble. There must, however, be some worthy objective at the bottom of their egotism, a reckoning with audience or craft that cannot be avoided. In mere fashion and in performative self-regard Talese has, on the evidence presented in A Town Without Time, not only not much interest but not much patience. His report from the world of fashion journalism, “Vogueland” (1961), and a longer piece on George Plimpton’s louche Paris Review crowd, “Looking for Hemingway” (1963), are written mainly in tolerant amusement, but Talese occasionally lets this mask slip, revealing behind it something close to contempt for people and behavior that he regards as frivolous. (“[T]hough they mostly came from wealthy parents and had been graduated from Harvard or Yale, they seemed endlessly delighted in posing as paupers and dodging the bill collectors.”)

Talese is an elegant and unmannered stylist, but he is not especially quotable, because the relevant unit of measure with him is the paragraph, not the sentence. Here he describes the years that the Times executive, Clifton Daniel, spent in London during World War II, years that proved crucial for Daniel both professionally and personally:

London in those days . . . was a great city for young American journalists. . . . The Americans and British in London shared a warmth and common purpose . . . If an American, particularly a well-tailored bachelor, also possessed, as did Clifton Daniel, a certain formality and reserve and understated charm . . . then London could be an even more responsive city; and for Daniel it was.

This quotation contains no striking image, no unusual coinage, nothing, even, that calls attention to itself—and yet what authority it possesses. Indeed, the prose here seems unconsciously to perform the very “formality,” “reserve,” and “understated charm” that it ascribes to Daniel. One almost has to read it twice to realize that the subject under discussion is sex.

Talese has spoken about the influence on his early work of New Yorker short story writers such as John Cheever and John O’Hara, particularly their attention to the nuances of behavior, speech, and dress. (“[O’Hara] . . . told us what Americans said, how they lived, the details of the clothing, the shoes, the cars.”) Human vanity, particularly as expressed in the competitive scrum of urban life, fascinates Talese. Yet his tone is not satirical but understanding, tactful, and usually forgiving. It is not that Talese is necessarily an easy man; one imagines that he addresses slights directly and forcefully. Rather, his principle seems to be: to those who show respect, respect will be returned. In this way, he must have comprehended the underworld figures of Honor Thy Father, not out of tribal loyalty, but from a kinship of temperament, a shared strategy for stepping through a heavily mined social world.

As now seems inevitable, Talese’s long career has intersected with public controversies over the boundaries and methods of elite journalism. Talese does not use a tape recorder when he conducts interviews, for example, preferring to reconstruct his subjects’ dialogue from memory. (He has said that “the worst thing that ever happened to serious nonfiction writing” was the tape recorder.) In preparing his portraits, he establishes an intimacy with those subjects that might be thought to cloud his objectivity, and he has acknowledged making an effort, at times, to protect their reputations, for which he offers no apologies. A late career book, The Voyeur’s Motel (2016), about a motel owner who spied on his guests’ most intimate encounters, was attacked for its veracity and for the potential ethical traps inherent in Talese’s own role as a participant-journalist.

It may be that journalism stops being journalism at the moment that it seeks to become art, that is, when it begins to seek permanence. By this reckoning, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” is not journalism but literature, full stop. Of course, Talese did a good deal of traditional journalism before he won fame by pushing its boundaries. (For several years Times editors tried, with some pointedly unpromising assignments, to break him of his literary ambitions and return him to the more stenographic style for which the paper was then known.) Has he had several careers in succession, or is his one long, unbroken career, in which his reporter’s deep curiosity about other human beings has simply extended itself through more various and sophisticated means? If it is indeed one career, it has been held together by a strong and somewhat eccentric personal ethos. For Talese, the protection of his private integrity is important enough to risk public misunderstanding or obloquy.

In interviews, Talese locates his origins as a writer in a boyhood spent working in his mother’s dress shop. “I would listen to my mother’s customers, these middle-aged women . . . talk about their lives, usually complaining . . . I observed people and I eavesdropped . . . and my imagination was enlarged.” One can easily picture the scene, the well-tailored little boy quietly folding boxes behind the three-panel mirror as those women gave themselves away in unselfconscious exposition. But whether the reporter’s temperament was formed by the experience of the dress shop, or whether the dress shop—not, for most of us, a place of inherent fascination—was made rich and vivid by the esurient mind of its observer, is impossible to say. Why do we become one thing and not another? As Talese’s work itself shows, the mystery of human personality is inexhaustible.

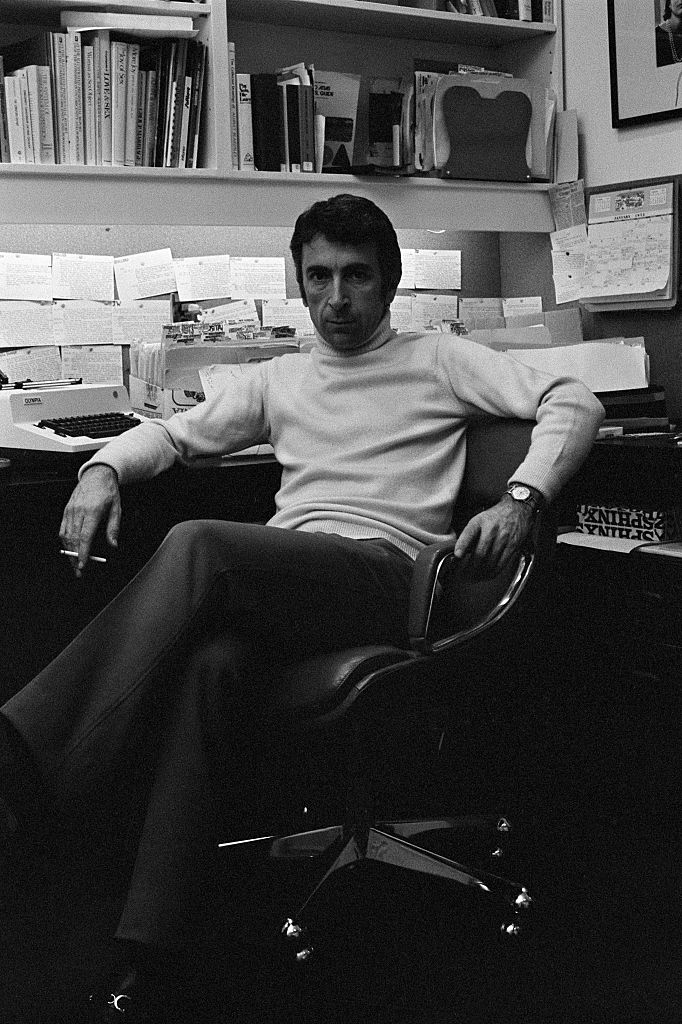

Top Photo: Gay Talese in 2012 (Photo by Randy Brooke/Getty Images)