“In this world there are only two tragedies,” says Mr. Dumby, a character in Oscar Wilde’s play Lady Windemere’s Fan. “One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. The last is much the worst, the last is a real tragedy!”

In 2016, Chicago Cubs fans got what they wanted: their team won the World Series for the first time since 1908, breaking the longest spell cast over any organization in North American professional sports. Those who lived to see the fulfillment of hopes that their fathers and grandfathers had taken to the grave exulted. Two days after the Series concluded, 5 million people turned out for a parade that started at Wrigley Field, the Cubs’ home since 1916, and ended with a rally in Grant Park. According to The Plan (2017), by Chicago sports journalist David Kaplan, it was the seventh-largest gathering of human beings in history. “Let’s hope that it’s not another 108 years,” Cubs manager Joe Maddon told the crowd. “Let’s see if we can repeat this and come back next year.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But the Cubs did not win the 2017 World Series. Or lose it. Nor have they played in any subsequent one. Indeed, they are one of only six Major League teams that have not won a postseason game of any sort since 2017. And even though Major League Baseball has expanded its playoffs to include 12 teams (40 percent of MLB’s 30 franchises), the Cubs have not played well enough to advance beyond the regular season in the past four years, something that 23 of the other 29 teams did at least once in that span. No Cubs fan has come to regret 2016. But the championship proved as disorienting as it was thrilling, and neither the fan base nor the Cubs organization has found its footing over the subsequent eight years.

Yes, Maddon got carried away in the moment. He knew, better than the 5 million celebrants, that if something is hard to do once, which winning the World Series is, then it will be extremely hard to do twice in a row. No team has won consecutive World Series since the New York Yankees secured their third straight title in 2000.

Cubs fans, too, could be forgiven their irrational exuberance about additional championships in the immediate future. For generations, the team’s futility was so consistent that it seemed encoded in the universe’s operating system. The 2016 Cubs were not only 108 years removed from the franchise’s most recent World Series victory, but 71 years removed from its most recent World Series appearance. Chicago reached the World Series seven times between 1908 and 1945, which is more than respectable, but the team’s history after 1945 consisted of long stretches of ineptitude punctuated by brief competitive intervals that culminated in dashed hopes and heartbreak. From 1947 through 1962, the Cubs had 16 consecutive seasons without once recording more wins than losses. They played 23 consecutive seasons, from 1946 through 1968, without winning a National League pennant and then, after MLB expanded and reorganized in 1969, another 15 without winning the NL East Division. By my calculations, if league and division titles were awarded randomly, the odds against a team failing to make the postseason even once for those 38 years would have been 0.37 percent, or 273-to-one. Over seven humiliating decades after 1945, Cubs fans watched 27 franchises reach at least one World Series, 12 of which were expansion teams created between 1961 and 1998.

Disappointing as the Cubs have been since 2016, they are Chicago’s least bad professional sports franchise. Chicago is the only city to have been home to more than one MLB franchise continuously since 1900, but the American League’s Chicago White Sox have an increasingly tenuous claim to being a Major League team. In 2024, they lost 121 games, more than any team in MLB history. Since winning the World Series in 2005, the Sox have missed the postseason 16 times in 19 years and never managed to win more than a single game the three times they did make the playoffs. The city’s other major sports teams—the Bears in football, Bulls in basketball, and Blackhawks in hockey—are all equally forlorn, consistently missing the playoffs year after year for the past decade, despite playing in leagues that have expanded the postseason so that even mediocre teams qualify.

One silver lining is that the grim resignation besetting the soul of the Chicago sports fan is highly adaptable to every aspect of life in or near the city. Chicago attorney and author Thomas Geoghegan has described Chicagoans’ default emotional setting as “comfortable Chekhovian despair.” It has many sources: harsh winters, an association in the world’s mind with organized crime, the more frightening quotidian reality of random, disorganized crime, endemic and ineradicable political corruption, the failure to establish a clear raison d’être in the postindustrial economy, a city population that has declined 26 percent from its 1950 peak and is now smaller than it was in 1920, and steadily receding importance in the nation’s culture and consciousness. The Chicago Tribune recently observed that “Chicago’s downtown vacancy rate is still double its pre-COVID levels, with a record 25% of its commercial space sitting empty.” In addition to “perpetual budget crises,” the city has $51 billion in pension debt, a higher total than 43 of the 50 states.

Those lacking an aptitude for stoic forbearance tend to be overrepresented in the diaspora from northeastern Illinois to warmer, safer, better-governed locales. The same process of natural selection shapes the experience of being a Chicago sports fan. Cubs fans, in particular, took perverse pride in supporting their “lovable losers.” Any sunshine patriot could cheer for a juggernaut, but devotion to a team that kept devising fresh ways to disappoint required a much deeper commitment.

It did not seem outlandish, then, to hope that 2016 marked the beginning of a radically more successful epoch in Chicago Cubs history. If the first championship since the Teddy Roosevelt administration could happen at the end of the Barack Obama administration, then anything could happen, including a long reign as one of baseball’s dominant teams.

Moreover, the new owners and managers, who spoke with enormous authority after engineering the World Series championship, had assured fans that enduring excellence was the goal. The subtitle of Kaplan’s book referred to “the audacious blueprint for a Cubs dynasty.” The objective was not, as Joe Maddon had said, to end one drought only to begin another.

In 2011, the chairman of the Cubs, Tom Ricketts, hired Theo Epstein as the team’s new president. Ricketts’s family had purchased the franchise from the Chicago Tribune corporation in 2009. (The board members were his siblings.) Epstein, already a legend at the age of 37, was the general manager who had assembled the Boston Red Sox team that won the 2004 World Series, the first championship for that franchise since 1918. “We’re going to make building a foundation for sustained success a priority,” he said during his introductory press conference at Wrigley Field. “That will lead to playing October [postseason] baseball more often than not. Once you get in in October there’s a legitimate chance to win the World Series.” Chicago fans were aware that Boston had won a second championship in 2007 and had made the playoffs three other times before Epstein’s departure following the 2011 season. And, after 2016, they were also aware that the Cubs were one of the youngest teams ever to have won the World Series, with six key players under 25.

But the Cubs’ success was sustained only briefly. The eight years since 2016 have unfolded in two phases: a decline, and then a rebuild that has yet to reach even modest goals. In the first phase, from 2017 through the midpoint of the 2021 season, hopes of perennial contention gave way to the reality of a team that did worse every year, even though the heroes of 2016 remained as the Cubs’ core. Over the five seasons after 2016, the Cubs stopped winning postseason series, then stopped winning postseason games, and finally stopped qualifying for the postseason altogether. Despite an achievement in 2016 that had eluded 49 previous Cubs managers, Maddon was fired at the end of the 2019 season. Epstein resigned after 2020, succeeded by his second-in-command, Jed Hoyer. By the middle of the 2021 season, Hoyer had traded or released nearly every player from 2016. The one holdover, pitcher Kyle Hendricks, who remained on the roster through 2024, has now also departed as a free agent.

Why does the 2016 World Series stand as a dominant season rather than the beginning of a Cubs dynasty? There are many theories but no consensus. After 2016, the Cubs experienced injuries, some older players’ decline, year-to-year variations in player performance, and personnel moves that didn’t work out. But so does every team, all the time. Nothing about the Cubs’ vicissitudes sets them apart.

The subsequent inability even to approach the standard set during their championship season justifies the suspicion that there was less to the 2016 Cubs than met the eye. Devoted Cubs fans won’t want to hear it, but after a century of bad luck, the team may have used up its allotment of compensatory good luck in just one year. The 2016 Cubs were unusually fortunate in two respects. First, their starting rotation was certainly good, but also remarkably healthy. Five pitchers accounted for 152 starts in the team’s 161 regular-season games. That’s not how the sport is played in the twenty-first century, when it is possible to acquire a working knowledge of orthopedic surgery and rehabilitative medicine by watching MLB TV.

Second, the 2016 Cubs happened to be baseball’s best team in a year when no others were exceptionally good. The St. Louis Cardinals, Chicago’s historical nemesis, failed to make the playoffs that season. The Cubs’ path to the World Series required them first to defeat the San Francisco Giants, who had won the World Series three times in the preceding six years but were clearly in decline by 2016. (They had a losing record in each of the next four seasons.) The next hurdle was the Los Angeles Dodgers, who established themselves as the National League’s dominant franchise after 2016, but not during.

And, in the World Series, the Cubs faced the American League champion Cleveland Indians (renamed the Guardians in 2021), a team that relied on good role players more than stars and entered the Series with half its starting rotation sidelined by injuries. Even when its starters were healthy, Cleveland had won nine fewer games than the Cubs during the regular season. The exhilaration of breaking a 108-year-old curse caused Cubs fans to disregard warning signs that, in retrospect, were there to be seen. A Cubs team with true dynastic potential should have beaten Cleveland decisively, rather than: a) losing three of the first four games; thereby b) needing the full seven games to prevail; and c) requiring extra innings and storybook heroics to triumph in a dramatic Game Seven.

Among those who overinterpreted the championship roster’s potential: the Cubs front office. Theo Epstein admitted as much. He fully expected the core of the 2016 team “to grow into an unstoppable set of players if we could continue to supplement them and show faith in them,” he said after the 2019 season. “I’ve made decisions to pour a lot of resources—every available dollar we’ve poured back into plugging holes for this group.” The “winner’s trap” that Epstein described afflicts organizations outside professional sports, making it grist for business-school case studies. “If I could do it again, as a leader, I’d try to find a way to be more objective and more critical.”

Jed Hoyer has been less sentimental than his predecessor but also, to date, less successful. After the 2021 season, during which Hoyer released or traded the stars remaining from 2016, Tom Ricketts issued a public letter to the fans, which described the process begun in 2021 as “Building the Next Great Cubs Team.” After four years of this endeavor, it is harsh but accurate to say that there has been a good deal of building but very little greatness. From the outset of the 2021 season to the end of 2024, the Cubs lost 52.6 percent of their games. That works out to an average of 78 wins and 84 losses per season, worse than all but 12 of MLB’s 30 teams.

It’s not just that the Cubs have had little success, but that no one who follows the team or is knowledgeable about the sport fully understands the team’s strategy to succeed. “The Cubs don’t really have a clear on-field identity or a coherent off-the-field message,” The Athletic’s Patrick Mooney wrote after the 2022 season. And as a result, “Virtually all of the goodwill generated from the 2016 World Series is gone.”

Another Cubs beat writer, ESPN’s Jesse Rogers, told Mooney in a 2024 podcast interview that the Cubs are a big-market team that acts like a medium-market team. This matters because no other American professional sports league has done a worse job than baseball of decoupling market size from athletic performance. Major League Baseball retains the every-tub-on-its-own-bottom business model that made sense before broadcast rights and free-agent players but now permits franchises in the biggest metropolitan areas to operate on an entirely different scale from the rest.

The New York Yankees and the Baltimore Orioles compete in the same American League division, for example, but are scarcely in the same business. Over the past four seasons, according to data from the Fangraphs website, the Yankees have spent 2.8 times as much on player salaries as the Orioles, an average of $270 million per year, compared with $97 million. This disparity is directly related to the fact that the Yankees play in the nation’s most populous metro area, with some 20 million residents, while the Orioles play in the 20th-most populous one, which has about 2.8 million people, one-seventh as many. By contrast, in the National Football League, the most popular, prosperous, and successfully managed sport in the country, the primary revenue source is national contracts with TV networks (and, more recently, streaming services), generating funds shared equally by all 32 franchises. In 2023, the Baltimore Ravens had the NFL’s highest payroll, while the New York Jets had the fifth-highest and the Giants ranked tenth.

In these circumstances, an MLB franchise has two main paths to achieve sustained excellence, where reaching the postseason is the expectation rather than an anomaly. One way is to be a big-market team that outbids competitors for the best players. The 2024 World Series, which crystallized MLB’s competitive balance crisis, featured the Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers: teams with two of baseball’s three biggest payrolls—the New York Mets being the other—based in the country’s two largest metro areas. Between them, the Yankees and Dodgers employed ten of MLB’s 33 highest-paid players, the stars most likely to dominate on the field and compel fans’ attention.

The other approach, obligatory for teams that cannot compete checkbook-to-checkbook with mega-market franchises, is to run operations that are exceptionally disciplined, shrewd, nimble, and efficient. The most heralded example of a successful small-market team is the Tampa Bay Rays. Over the past four seasons, they have had the sixth-best record in baseball, an average of 91 wins and 71 losses, but only the 26th-highest payroll, roughly $115 million per year.

Neither paradigm describes the Cubs, who spend less extravagantly than the Dodgers and Yankees, but less effectively than the Rays. From 2021 through 2024, the Cubs achieved the 18th-best record in baseball with the 12th-highest payroll, an average of $202 million per year. Seven of the 18 teams that spent less on payroll than the Cubs in those years—Baltimore, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Minnesota, Seattle, St. Louis, and Tampa Bay—won more regular-season games. Two of the others, Texas and Arizona, faced each other in the 2023 World Series. Only one of the 11 teams that spent more on payroll than the Cubs, the hapless Los Angeles Angels, won fewer games. The Angels’ payroll was about $1.6 million more per year than the Cubs’; their average season record was 72 and 90, worse than all but seven other teams.

The two approaches—spend massively; spend brilliantly—are, of course, not mutually exclusive. There’s nothing to prevent a team with vast resources from spending them as efficiently as the small-market brainiacs. The most direct way is for a large-market behemoth to hire a small-market brainiac, as the Dodgers did in 2014 when they signed Tampa Bay’s general manager, Andrew Friedman, to be their president. A team that spends as much as the Dodgers and as well as the Rays has a real chance to reach the goal it clearly intends, which is to become baseball’s Death Star.

The Cubs attempted a smaller-scale version of this coup in 2023 when they hired manager Craig Counsell away from their neighbor and division rival, the Milwaukee Brewers. Milwaukee, the National League counterpart to Tampa Bay, finished 19th in payroll outlays from 2021 through 2024, spending just under three-fourths as much as the Cubs (or about $55 million less per year), while winning an average of 92 games per season, the fifth-highest MLB total and 14 more per year than Chicago. To put the comparison differently, each one of the Cubs’ regular-season victories from 2021 through 2024 cost the team about $2.6 million in payroll expenditures. Each of the Brewers’ wins cost Milwaukee $1.6 million. If the Cubs had married their recent level of spending to the Brewers’ level of efficiency, Chicago would have averaged an unimaginable 126 wins per year, ten more than the record set in the modern era by the 2001 Seattle Mariners.

Counsell has four years left on his five-year contract, which made him the highest-paid manager in the game and may yet prove to be worth every penny. The early indication, however, is that he was not the main ingredient in Milwaukee’s secret sauce. The Brewers won 92 games with Counsell in 2023, and then won 93 without him in 2024. Conversely, the Cubs won 83 games without Counsell in 2023 . . . and 83 games with him in 2024.

Hoyer describes his approach to building the next great Cubs team as “intelligent spending,” which ESPN called an “ambiguous concept” and which The Athletic said had become “a punchline” among more caustic Cubs fans. The goal is to “find value in deals and undervalued players,” Hoyer said before the 2024 season. Whatever intelligent spending entails, it’s clear what it rules out: trading for or bidding on the biggest stars, the kinds of players on track for the Hall of Fame.

In contrast to Hoyer, who vows not to be “profligate,” Friedman once said that the Dodgers’ approach to roster building rested on the principle that “If you’re always rational about every free agent, you will finish third on every free agent.” Over the past four years, the non-profligate Cubs have had payrolls that are two-thirds to three-quarters as large as those of the big-spending Mets, Dodgers, and Yankees. Just behind those three are the Philadelphia Phillies, whose owner went Friedman one better in 2018 by announcing his intention to spend money on star free agents, “and maybe even be a little bit stupid about it.”

Parsing Hoyer’s cryptic words in light of his actions, the best guess is that he sees the Cubs as an organization that resembles either the Houston Astros, who play in the country’s fifth-largest metro area, have had the seventh-highest payroll outlays over the past four years, and have had the third-largest number of regular-season wins; or the Atlanta Braves, located in the sixth-largest metro area, with the sixth-highest payroll, and second-highest win total. Both franchises, in other words, spend more than the Cubs but less than the New York and Los Angeles colossi, and then make up the difference on the diamond with the kind of small-market ingenuity that gets the most out of every dollar and every player.

The results speak for themselves. Houston played in the American League Championship Series every year from 2017 through 2023, advanced to the World Series four times, and won it twice. The Braves also won the World Series, in 2021 (against Houston), and have not missed the postseason since 2017. Any such outcome would appease Cubs fans, who are starting to wonder whether they are eight years into the team’s next 108-year drought. As the title of a 2023 book on the Astros had it, Winning Fixes Everything.

Until and unless the winning starts, however, the brokenness remains. Sports fans care about a team, rather than regarding it as a simple source of entertainment, for two reasons. First, a team connects people across time, as they grow up watching games with their parents and grandparents and go on to watch them with their children and grandchildren. Second, it connects those attached to a particular place. Baseball is Greek, Jacques Barzun wrote in 1954, “in being national, heroic, and broken up in the rivalries of city-states.” The pride we take in the success of “our” team is bound up in its role as an emblem of our home.

Cubs fans thought that the 2016 World Series meant not only that the team would be competitive on the field for years to come but be competitive with teams from the biggest cities in signing the game’s superstars. The past eight years have shown otherwise. Not even the revenue surge after 2016 allowed the Cubs to outbid the Yankees for Aaron Judge, the Dodgers for Shohei Ohtani, or the Mets for Juan Soto. Chicago, the “Second City,” has really been the Third City since 1984, when Los Angeles surpassed it in population, and is perhaps a decade away from becoming the Fourth City when it is overtaken by Houston. Seen in that light, the 2016 championship looks like an outlier, not just in the history of a star-crossed franchise, but in a lower-echelon city punching above its weight.

The Cubs may recalibrate and succeed by emulating the Braves and Astros, but even that path would demonstrate Chicago’s declining importance, a second-tier city that cannot dismiss the possibility that it will fall to an even lower rung. Since 2000, the Chicago metro area population has increased only one-fifth as much as the United States overall—3.8 percent, compared with 19.4 percent—while metro Atlanta and Houston have grown to a far greater degree, 53.4 percent and 79.5 percent, respectively. Metro Atlanta now has two-thirds as many residents as Chicagoland; the Houston metro area is four-fifths its size.

Is Chicago, Thomas Geoghegan asked in 1985, “really any different from St. Louis, Detroit, or Indianapolis?” The question cuts deeper than it did four decades ago. Long-term, the Cubs’ hopes for sustained success depend in large part on two factors beyond the team’s control. One is whether MLB solves, or at least reduces, its balance problem, so that fans of all 30 franchises, not just those in the biggest cities, can plausibly hope for World Series parades. The second is whether Chicago solves, or at least reduces, its competitive problem, enabling the city and metro area to retain the residents and business already located there and attract new ones from across the country and around the world. Pending these developments, Cubs fans subsist on YouTube highlights of that 2016 championship season. Though still gratifying, the videos also elicit the very Chicago sentiment that our best days lie behind us, not ahead.

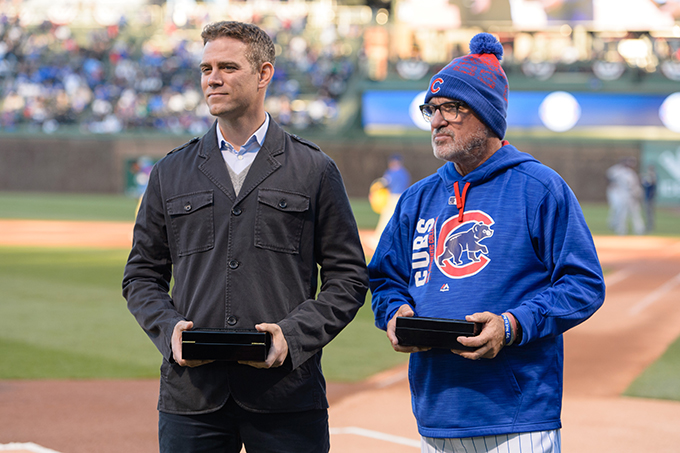

Top Photo: In 2016, Cubs fans celebrated the team’s first World Series title in 108 years. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Source link