In the previous installment of this column, I reflected on the present-day significance of Adam’s vocation to avad (“till” or “cultivate”) and shamar (“keep” or “care for”) the Garden of Eden.

At that time, I explained that these terms carry overtly priestly overtones within Sacred Scripture—a theme evident in the deliberateness with which the primordial injunctions given to the first man are deployed elsewhere in Scripture to describe the liturgical duties of Israelite priests. With this in mind, I underscored how Adam (literally, the adam) is the archetypal human being—man, the priest of creation, who has been placed on earth to cultivate obedience to God’s law and tend the garden of the earth.

Yet, the sobering reality is that believers have not always lived according to the ethos of sacrificial love that marks our vocation as priest-kings of creation. All too often, our ministry over creation ends up directed primarily in service toward ourselves. Put differently, our vocation to loving dominion over creation often becomes one of unbridled domination.

Herein lies the impetus for the present reflection: observing this destructive tendency in the Western world, environmentalists frequently attribute its origins to the Judeo-Christian tradition—the Bible in particular. Today, I want to lay the groundwork for a refutation of this claim by pondering two further concepts that are often seen as conflicting with genuine care for nature: what Genesis 1:28 means with the injunction to kabash (“subdue”) and radah (“have dominion over”) the earth.

Dominion in its ancient biblical context

If there is to be any rebuttal of the claim that the Judeo-Christian vision of man’s dominion over creation is responsible for our present-day ecological crises, we need to go back and retrieve the original meaning of radah—authentic dominion as intended in Scripture.

At first glance, this concept might seem to suggest an unrestricted right to exploit nature on the part of man. Admittedly, such an interpretation is indeed possible when taken out of context (something that should come as no surprise, seeing as the same can be said for many passages in Scripture). Because of this, Pope Francis has emphasized that the ancient commands of Genesis must be “read in their context, with an appropriate hermeneutic,” adding that “we must forcefully reject the notion that our being created in God’s image and given dominion over the earth justifies absolute domination over other creatures.”

To read Scripture through the right lens, paragraph 390 of the Catechism underscores that its earliest chapters were composed in “figurative language” in accord with the literary style of its ancient Near Eastern cultural milieu centuries before Christ’s coming. In the words of Pope Benedict XVI, the opening chapters of the Bible convey God’s revealed word by means of “recourse to images.”. With this in view, paragraph 452 of the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church highlights the enduring significance of the Garden of Eden, noting that it symbolizes not only the primeval paradise of our first parents but also the world we all are called to inhabit today—“the garden that God has given [man] to keep and till.”

Reading Genesis in accordance with its ancient literary genre allows us to see why the true biblical concept of dominion is not one of exploitation. As noted commentators Ellen Davis and Richard Bauckham have independently emphasized, dominion in the opening pages of Genesis is a form of governance in which humanity exercises responsibility not so much over nature as within creation and among other creatures—much like a shepherd who watches over his sheep by living among them and sharing in a common life. Shepherds do not abuse their flocks. Even though they could, it is obvious that doing so would ultimately leave them with no flock at all.

In the same way, exercising dominion over creation could theoretically be interpreted as a license for unchecked exploitation, but this would ultimately lead to consequences that undermine the very purpose of enjoying dominion over creation in the first place.

Another way to understand the biblical concept of man’s dominion over nature is to see it as a reflection of the Lord’s dominion over us—a rule that is surely not one of exploitation but of nurturing, covenantal love. The implication of this connection is articulated well by Terrence Fretheim when he notes: “As the image of God, human beings should relate to the nonhuman world as God relates to them.” Just as God exercises his lordship over us by welcoming us into his family, the Christian tradition teaches that our covenantal communion with the Trinity should, by analogy, extend to all of creation.

Dominion as Christo-centric, priestly mediation

To gain insight into the proper way to exercise dominion over the natural world while living among other creatures, it is hard to think of a more fitting model than to consider how God became one of us. In the person of Jesus Christ, God truly dwells with and among us, exercising royal governance over us in the form of love, not raw subjugation. Just as Christ unites humanity and divinity as true God and true man, so, too, St. Bonaventure understood that human beings occupy a unique niche within creation. As the Seraphic Doctor underscored, men and women “stand in the middle” of the cosmos, seeing as human nature is a union of the spiritual and physical, midway between the angels and all terrestrial creatures.

Within this framework, the great Franciscan theologian envisioned mankind’s dominion over nature as a vocation of mediation in which man, as a rational creature, shepherds lower creatures towards their fullest potential in God. This concept was captured well by Joseph Ratzinger in a reflection on the dignity of the human person when he said that the key to dwelling rightly within creation “must ultimately consist in bringing things into man’s glorification of God.” The Catechism likewise foregrounds this dynamic when it teaches: “God created everything for man, but man in turn was created to serve and love God and to offer all creation back to him” (par 358).

This traditional understanding of the human person as the nexus of all creation is profoundly liturgical and priestly in character. Yet, even as we say this, it can be helpful to address another concern that some in the environmental movement might have when seeing humanity’s role in creation being described in sacerdotal terms. In society today, the priesthood is commonly misrepresented as an exclusive ruling class whose main objective is to seek power for themselves by standing above those to whom they minister.

In reality, though, the Catholic tradition holds that a priest is better thought of as a servant who stands in the midst of his community, which is precisely what enables him to serve as its mediator (with the pope being the “servant of the servants of God”). Such was the case for Israel’s kings. While plenty abused their mandate to rule through service, the standard for kingship in Israel required that the king be chosen “from among” his brethren and that “his heart must may not be lifted up above his brethren” (Deut 17:15,20). By extension, the concept of dominion over creation as envisioned in Genesis requires man, the priest-king of creation, to cultivate a profound horizontal relationship, not merely a vertical one, with his fellow creatures.

Recovering this understanding of the priestly rule can help us to reframe the tired dispute over whether man enjoys a status “above” the rest of creatures or merely occupies another place “in the midst of” them. For the Catholic, it is clear that man holds a position above other creatures, yet this exalted authority is fundamentally ordered toward a service that requires us to live in the midst of them. This is especially clear to Christians, who know Christ’s teaching that “whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all” (Mk 10:44–45).

Although many environmentalists are loath to do so, the Catholic Church contends that acknowledging man’s status as the “greatest” in creation is essential for cultivating meaningful concern for it. For, as Pope Francis has noted, it is hard to explain why humans should be expected to exercise responsibility for the world if our species is not endowed with special dignity and unique gifts (see Laudato Si’, paragraph 118).

“Naming” creatures and what it means to “subdue” the earth

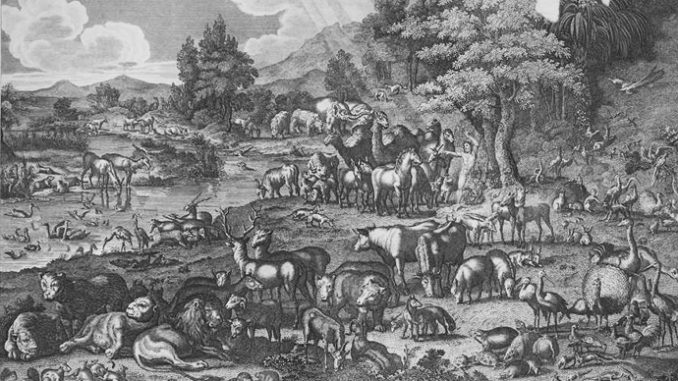

As we have seen in the case of radah (dominion), a careful examination of Genesis in its original context reveals that the mandate to “subdue” (kabash) the earth is not inherently opposed to a respectful relationship with creation. To be fair, kabash can be deployed in contexts that involve violence and subjugation. For example, this verb is used elsewhere in the Pentateuch in relation to Israel’s “subduing” (i.e., ruthlessly conquering) her enemies. In the case of Scripture’s earliest chapters, however, kabash signifies a unique dynamic in which other creatures are subject to man as their benevolent king while simultaneously dwelling with him as his covenantal companions. In their own way, these pages present a profoundly “green” vision, yet without relying on the modern framework of animal rights. In fact, the eminent commentator Gordon Wenham goes so far as to describe Noah as “the arch-conservationist who built an ark to preserve all kinds of life from being destroyed in the flood.”

This relationship is evident already in the first step man takes toward subduing the earth: the naming of creatures (Gn 2:19–20). To name is to wield power by establishing a relationship. It implies a desire and commitment to establish a connection with the creatures we name, to bring them into our human orbit. This reality becomes clear when we reflect on our everyday experience of naming creatures. For instance, many of us recognize that a cat or dog takes on a new character within our lives when we make it our pet and give it a name. Indeed, many people consider that pet a bona fide part of their family (although this requires balance and nuance, as Pope Francis has lamented the trend in our society of viewing dogs as substitutes for children and permitting them to assume that role).

In an analogous way, even something so simple as learning the names of the various flora and fauna that inhabit our neighborhood can profoundly shape the way we relate to them, often leading them to be seen as companions or friends. As my wife likes to point out, we have much to learn here from little children, who form immediate bonds of friendship with creatures simply by learning their names. By learning to become like little children in this way, we can take a small yet meaningful step toward overcoming the alienation that results when we habitually allow the technological works of our hands to distract us from what is truly the closest to us.

In the world of Genesis, the act of naming was understood as a participation in God’s providential rule over the earth, a sacred trust in which God has entrusted man with a share in his own work. As John Paul II taught, Adam’s vocation of naming the animals was “the sign of this mission of knowing and transforming created reality,” which “is not the mission of an absolute and unquestionable master, but of a steward of God’s kingdom who is called to continue the Creator’s work.” Benedict XVI likewise viewed man as a collaborator in God’s own work as a free agent capable of willing the good of those entrusted to his care. In this connection, the Bavarian pontiff stressed that the task of “subduing creation“ was never intended as an order to enslave it but rather as the task of being guardians of creation and developing its gifts.”

Here, too, understanding something of Genesis’s ancient context sheds light on its present-day significance. In the line I just cited, Pope Benedict noted that we who bear God’s image are guardians of creation. This is important. We may be the only species to bear the divine image and likeness, but we are no more owners of the earth than the Promised Land was Israel’s absolute possession. In both instances, we are more accurately seen as tenants or vice-regents who partner with the Creator in his supreme ownership, and our tenancy on the Lord’s land is contingent upon our proper stewardship of his handiwork. As the Lord told the Israelites, “[T]he land is mine; for you are strangers and sojourners with me” (Lev 25:23).

And, yet, in the fullness of time, it has been revealed that our role in creation extends beyond that of mere stewardship As Jesus taught, we are no longer mere servants, but friends of God (Jn 15:15). Indeed, from the perspective of the New Testament, we are his adopted children, with all the rights and privileges pertaining thereto (1 Jn 3:1–2). Having entered into a covenant with the Creator of the universe through baptism, we are destined to “inherit the earth” (Matt 5:5) as co-heirs with Christ (Rom 8:17).

Bearing this in mind, we arrive at a similar conclusion as in the case of dominion: it becomes patently nonsensical for us humans to regard ourselves unqualifiedly as masters of creation, possessing an unrestricted authority to exploit it at will. To grasp this point, we need only consider: Who is more invested in the welfare of the creatures entrusted to him and therefore more likely to tend to them with care: the shepherd who loves them and to whom they properly belong, or the hireling merely paid to watch over them in exchange for a profit (Jn 10:11–14)?

If we are sons and daughters of the King of Creation, then our rule should echo that of our divine sovereign—the Good Shepherd who assumes personal responsibility for the well-being of all subjects in his kingdom.

All the more so is this the case if the creatures we are called to “name” are themselves family—or, as Genesis 9 envisions, other creatures—our extended covenantal kin. I find that this reality is expressed well through an analogy with parenting: Just as those who have the responsibility of naming children are not given free rein to treat them however they please, so too does Scripture portray man’s role as one of stewardship—living in true communion with our fellow creatures while holding a position of authority in their midst. Accordingly, just as parents exercise a certain dominion over their children yet inflict grave damage on their relationships when they resort to domination, a parallel dynamic obtains when it comes to man’s relationships with other creatures.

Ratzinger thus states: “[E]ven if they do not have the same direct relation to God that man has, they are still creatures of his will, creatures we must respect as companions in creation.” Because of this, he emphasizes, “We cannot just do whatever we want with them.”

To reclaim the gift of creation and rediscover Eden today

Rooted in the testimony of Scripture and emphasized in the writings of recent popes, the Catholic tradition stresses the need for a fundamental metanoia in the way we inhabit God’s good earth.

A critical component of this renewal is to recover an authentically biblical understanding of what it means to exercise dominion and subdue the earth. As I have tried to establish, this is not a license to exploit creation as mere raw material for our desires, but a call to recognize and cherish it as the profound blessing that it truly is. In the words of Pope Benedict, “We must consider creation a gift that has not been given to us to be destroyed, but to become God’s garden, hence, a garden for men and women.”

Benedict’s phrasing here reveals a subtle yet important nuance: it is a gift with a future orientation. While he views the Garden of Eden as a symbol of man’s communion with God before the Fall, he also implies that the earth can take on the character of Eden in the present age if our manner of dwelling upon reflects its real status: not an entitlement we claim, but a gift we receive. In this, Benedict’s insight is just a contemporary expression of the revealed truth of Proverbs 3:18, which teaches that a life of wisdom enables us to partake of the “tree of life” even now.

Yet, if this truth is to be fully realized—and to avoid validating the allegation that the word of God is the ultimate source of our ecological problems—then we who believe must reclaim a deeply biblical understanding of creation and embody it in the concrete circumstances of our lives.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.