The epitaph on John O’Hara’s Princeton gravestone reads: “Better than anyone else, he told the truth about his time, the first half of the twentieth century. He was a professional.” Another Irishman, Jay McInerney, picked up the second half—or at least, a decade of it, the 1980s—and a city, New York. “It was a surprise to me when I started being hailed as a spokesman for my generation, as a definer of the zeitgeist,” he says.

McInerney is seated in the living room of his Greenwich Village penthouse, a midafternoon winter light illuminating a book-lined wall featuring F. Scott Fitzgerald first editions. This book section also includes Fitzgerald’s high school graduation portrait and his silver drinking flask—an instrument of the great American novelist’s demise at 44. In the portrait, Fitzgerald looks young and handsome, still a long way off from his lethal bad habits and the posthumous adoration. “He had a good early run,” quips McInerney, still youthful and handsome himself, at 70.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In 1982, The Paris Review published the short story that became the first chapter of Bright Lights, Big City, McInerney’s debut hit novel, which appeared two years later. Thereafter, McInerney was often likened to Fitzgerald—two writers chronicling despairing youth and upper-crust disaffection in their respective times. “I used to think that I had started reading Fitzgerald after I started getting compared to Fitzgerald,” says McInerney, who upon revisiting an early journal realized that he was reading him by college.

If anything, though, McInerney could be compared with a modern John O’Hara, who still holds the record for the most published short stories in The New Yorker, where McInerney had an early job as a fact checker. Beginning with Appointment in Samarra—his 1934 novel featuring a chilling second-person passage about how life falls apart—O’Hara wrote stories remembered for their precise documentation of how striving Americans once lived. O’Hara was known for his realistic dialogue, obsessive attention to sartorial tastes, and the idiosyncrasies, however mundane, of mid-century existence.

Similarly, to understand urban American life, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, requires a foray into McInerney’s O’Hara-esque portrayals. From Bright Lights, Big City through Brightness Falls (1992), McInerney shows an ear for the dialogue, an understanding of the bad habits, and an appreciation for the material tastes of the period’s upwardly mobile boomer and Gen X crowd. It’s cigarette smoke and St. Pauli Girl beer; Roxy Music vinyl on the stereo and Vanity Fair on the coffee table; Lacoste shirts and Paul Stuart suits—a late analog era when hedonism could still be pursued with some privacy.

Reading McInerney is also a rendezvous with enduring cultural fixtures. As the French say, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Take his 1985 Esquire profile of Mick Jagger. “Is it strange being a forty-year-old rock ‘n’ roller?” 30-year-old McInerney asks the Rolling Stones front man. “Forty-one. . . . Obviously, you can’t do it forever. But I can still do it,” responds Jagger, who, at 81, led the band’s latest national tour last year. Or McInerney’s 1994 New Yorker profile of Chloë Sevigny, the Manhattan “girl of the moment.” “It’s probably her spacey air of mystery and reserve as well as the street chic that keep causing people to ask, Who is that girl?” writes McInerney of Sevigny, who later acted in the film adaptation of his friend Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho. Today, at 50, Sevigny remains something of an “it girl,” both in fashion and on camera, starring recently in the Netflix series about the Menendez brothers—a show that perversely inspired Gen Z-ers, or zoomers, to revive the “old money aesthetic,” the preppy style associated with the yuppies found in McInerney’s stories.

“I think there’s a lot of nostalgia now for that period,” says McInerney, reflecting on the resonance of Bright Lights, Big City, a semiautobiographical account—told in second person—of a young man’s cocaine-fueled descent in New York’s early 1980s downtown scene. “There was no social media, there were no mobile phones, and life was certainly simpler then,” he reflects. “I’m still not sure how we found each other. Somehow, we managed to rendezvous in restaurants, nightclubs, and bars.” It was a time when the most distracting notification was a message left on an answering machine. “Story of my life, talking to machines,” the character Alison Poole laments in McInerney’s comic 1988 novel, Story of My Life. If she only knew what lay ahead.

As McInerney notes, there was no sense of the “1980s” when he wrote Bright Lights. “There hadn’t yet been this defining of the decade,” he says. Even then, the signs of vertiginous change—especially involving technology—were apparent, as McInerney predicted in Bright Lights: “The new writing will be about technology, the global economy, the electronic ebb and flow of wealth.” Now, though, many feel nostalgia for that era. “It’s darker now,” says McInerney, observing how a duct-taped banana sold for $6.2 million at an art action last fall. “The eighties look pretty quaint now compared to what’s happening.”

The story of McInerney’s life begins in Hartford and then proceeds with regular relocations. Born in 1955, he wasn’t an Army brat but a child of mid-century corporate mobility. His father, a Korean War veteran, worked in marketing—most notably, for Scott Paper Company, which was then headquartered in the Philadelphia area—and his varied roles took the family from that city’s suburbs and Westchester County to Vancouver and London. McInerney bounced around the land of John Cheever, always the new kid in town. “In a sense, it was all the same, which is why I’ve never wanted to live in the suburbs since,” he says.

McInerney grew up in a religious Irish Catholic household, though his maternal grandmother was Russian. “I like to say that I have drinking, depression, and literature on both sides of my family,” he jokes. In that Vatican II era, he served as an altar boy and was old enough to remember John F. Kennedy’s presidential run. “I embrace my Irish heritage,” says McInerney, “certainly as a literary heritage. It’s a good one, right?” As his family moved around, he turned to books and hid in his room. He read Jack London and Dylan Thomas and war histories; his discovery of Fitzgerald came later. From an early age, he wrote stories, with settings ranging from medieval England to World War II.

McInerney graduated high school in western Massachusetts, where he stayed and attended nearby Williams College. There, he studied English, reading Hemingway and Joyce—“After you read Ulysses, you think, what can you do after that?” He got into a fist fight with another student, Gary Fisketjon, caused by a rivalry over an attractive transfer student from Wellesley. Fisketjon and McInerney then became friends, bonding over their love for the work of Raymond Carver, best known for Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? Fisketjon would become editor to both Carver and McInerney, who later studied under Carver at Syracuse.

“Strangely enough, at that time, I didn’t really want to be in a city, but now I wouldn’t live anywhere but a city,” he says. By then, though, he had a sense that New York—“a literary center where all the books were published and little magazines come from”—was the place for a writing life. During McInerney’s formative years, literary figures like Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and Gore Vidal were regular TV presences on popular talk programs like The Dick Cavett Show. “So I had a sense that maybe New York was where you wanted to move if you wanted to become a writer,” he says.

But first, McInerney had a postcollege, two-year detour to Japan—serving as the basis for his second novel, Ransom—where he taught English on a Princeton fellowship. Upon his return, “I came directly to New York. And I haven’t really left since.” In Manhattan, McInerney felt that he truly belonged. “Nobody really cared where you came from,” he says. “As a New Yorker, your history before New York is uninteresting to other people. They don’t care where you came from. What they care about is what you can do now for them.”

McInerney arrived in Manhattan with his girlfriend, who became a successful fashion model, in 1979. He married her one year later, and after some freelancing, he took a supposed dream job as a fact checker at The New Yorker, doing research for contributor Jane Kramer. But his résumé wasn’t entirely accurate: “I claimed I was fluent in French, which I wasn’t.” A calamity ensued when he was tasked with verifying a Parisian-heavy piece by Kramer. Not long after, McInerney was out of a job.

The early 1980s marked a trifecta of cataclysms for McInerney: The New Yorker fired him; his wife left him after flying to Italy for a fashion show and falling in love with a photographer; and his mother died of cancer. He then left New York—“sometimes it felt like I was basically kicked out of the city”—enrolling in a graduate creative writing program at Syracuse and studying under Carver and Tobias Wolff. “I was going for my doctorate because I didn’t know what else to do,” McInerney recounts. But his first book emerged from those three experiences. “If you live a really placid life and nothing bad happens to you, then you’d better have a very vivid imagination,” he says.

The idea for what became Bright Lights, Big City had germinated in the summer of 1981, when he was going out at night to the types of New York bars that figure heavily in the novel. At one nightclub, around 3 am, he remembered looking in the mirror. “I had no money left. I had no drugs left. And I was going into despair,” he remembers. At that moment, he said to himself: “You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning.”

When he got home, he wrote down the line—the eventual novel’s first sentence—and stuck it in a drawer. He later submitted a short story draft to Paris Review editor George Plimpton, who liked it but asked for something else. McInerney rummaged through his notebooks and came upon “this little weird passage, and I thought, that’s interesting.” That night, he started writing the story that appeared in The Paris Review’s Winter 1982 issue. The story itself germinated into the first draft of Bright Lights, which he completed over six weeks in 1983. By Christmas, Random House had accepted his second draft, and he received half of a $7,500 advance, which allowed him to “fix my car and buy presents for people.” He was still living in Syracuse.

Published in August 1984 with an initial print run of 15,000 copies, Bright Lights, Big City became a word-of-mouth, overnight success and turned McInerney into a literary celebrity. “The New York Times didn’t get around to reviewing it until three months after it came out,” he recalls. “And by then, it had sold 150,000 copies.” Soon enough, McInerney found himself on The Today Show, interviewing Jagger for Esquire, and deciding that it was time for his Manhattan return. The novel took on a life of its own. It enjoyed pop-culture success, conjuring for many readers a romantic idea of Gotham decadence. Take this passage, in which the narrator revisits his old Greenwich Village neighborhood where he shared an apartment with his wife before she left him:

At the corner of Jones and Bleecker a Chinese restaurant has replaced the bar whose lesbian patrons kept you awake so many summer nights when, too hot to sleep, you lay together with the windows open. Just before you moved out of the neighborhood a delegation of illiberal youths from New Jersey went into the bar with baseball bats after one of their number had been thrown out. The lesbians had pool cues. Casualties ran heavy on both sides and the bar was closed by order of the department of something or other.

At the time, McInerney was thinking only about “story, language, structure,” not about a particular social scene. “I didn’t think at all that I was writing about a period so much as I felt I was exorcising some of my demons,” he says.

The novel led to a decade of notoriety, with McInerney losing any sense of privacy. In the late 1980s, when he was dating Marla Hanson—the model whose face was slashed in a brutal 1986 attack instigated by her landlord—“photographers were camped outside our doors.” He adds: “I’d go out to dinner with Bret Easton Ellis, and then the waiter would call Page Six and tell them what we were talking about.” It was the last time that literary figures could draw such attention. “What’s odd now, there’s a craving for attention; you have influencers now who want those paparazzi,” says McInerney. “They can have it.”

By the 1990s, married to his third wife, Helen Bransford, McInerney was splitting his time between her native Tennessee and New York; they became parents of twins. Brightness Falls, his 1992 novel, was a sweeping time capsule of late 1980s Manhattan, and it led to a series of novels about its protagonist couple: yuppies Russell and Corrine Calloway. McInerney also became a wine columnist, most recently for Town & Country. He married his current wife, heiress Anne Hearst, in 2006.

McInerney has continued on as a writer and bon vivant, but several cataclysms last year gave him “a stronger sense of mortality.” In February 2024, after a blood pressure–related nighttime fall, McInerney gashed his head. The bloody spill caused a concussion and a subdural hematoma. Weeks of monitoring passed, until one day when he was headed to dinner. “I got a call from the doctor’s office: ‘You have to go to the emergency room right now.’ ” He had emergency brain surgery the next day to stop the expanding subdural hematoma. Not long thereafter, in May, he started feeling shortness of breath and took a stress test. “Once again, I was raced into the hospital, and I had quadruple bypass surgery.”

Now, he feels recovered, but the ordeals came as a surprise. “I’ve been wildly healthy most of my life, despite my hard-living ways,” McInerney says. “I’m not supposed to bang my head up anymore,” he adds. “So I guess my surfing career is over. I guess my skiing career is over. But that’s okay. I had a great run.”

McInerney hopes to publish a memoir in the coming years. And the Calloways—revisited after 9/11 in McInerney’s novel The Good Life (2006), and then amid the Great Recession in Bright, Precious Days (2016)—will now enter the Covid era for what becomes a tetralogy. McInerney wrote the novel, titled See You on the Other Side, during the lockdowns. It is still in the editing phase.

“It was challenging because I write about social life, and there wasn’t that much social life during Covid,” he says. Looking back, as a Democrat, he thinks the party “made some real mistakes in terms of restrictions. I mean, why could you dine out in Westchester when you couldn’t dine out here in New York City? It’s like: what the fuck? Are germs more transmittable in the city than they are in the suburbs?” He also questioned the point of mask mandates. “There was very little evidence that they did anything.”

McInerney’s living room was warm and quiet, despite the icy winter winds pounding on the window that looked out on his terrace and beyond to the city. The art deco room felt timeless, but history was repeating and accelerating on that December day, with echoes of McInerney’s literary universe. That morning, President Donald Trump—a New York 1980s exemplar referenced in Brightness Falls, set in part in the fall of 1987, the year the future president published The Art of the Deal—rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange and was named Time’s Person of the Year. Trump had just scored the most commanding presidential victory for Republicans since Ronald Reagan in 1984. Back then, boomer men, in the mold of Family Ties’ Alex Keaton—played by Michael J. Fox, who starred in the 1988 film adaptation of Bright Lights, Big City—flocked to the GOP. This time, it was young zoomer men rallying to Trump.

The stunning political realignment, traces of it apparent even in Manhattan, surprised McInerney. “I don’t like woke culture, either, but it doesn’t mean I’m going to vote for Trump,” he says. But McInerney lamented the current state of publishing, including the big publishers’ employment of sensitivity readers. “I’ll tell you one thing, American Psycho would never get published in this era,” he says. McInerney also observes: “There’s a sense that white people aren’t supposed to write about black people, and men aren’t supposed to write about women, which I think is ridiculous, because if fiction is anything other than journalism, it’s imaginative projection into different consciousnesses. . . . Otherwise, it’s just journalism and autobiography.”

Today, McInerney’s stories and novels serve as a portal to the New York of a recent past that can feel more distant than it is, given the pace of technological change. Take this passage from The Story of My Life, where the narrator Poole describes the culture of cabs—an experience now all but vanished amid ride-hailing services like Uber and the more interior life of earbuds and phone screens:

You never know how many kinds of music there are in the world until you move to New York and start taking cabs. It’s like, from your apartment to Trader Vic’s you get Cuban music, and then from Trader Vic’s to Canal Bar you’ve got Zorba the Greek music and then Indian ragas from Canal Bar to Nell’s, Scandinavian heavy metal on the way from Nell’s up to Emile’s apartment. After that you start singing the Colombian national anthem.

That passage came from a time when literary figures like McInerney and Ellis, whose debut novel Less than Zero appeared 40 years ago, were widely known. But literary fame is not what it was. “There’s less of a literary center than there used to be. . . . And it’s pretty hard to think of anyone who’s lodged into the popular imagination,” he says.

McInerney, though, continues his reading life, alternating between contemporary fiction and the classics. And his habits remain analog. “When I go out, I still carry a book instead of a phone,” he says. Sitting on one table, near the adjoining hallway, was the latest from Gay Talese. “I’m always hauling books around with me.”

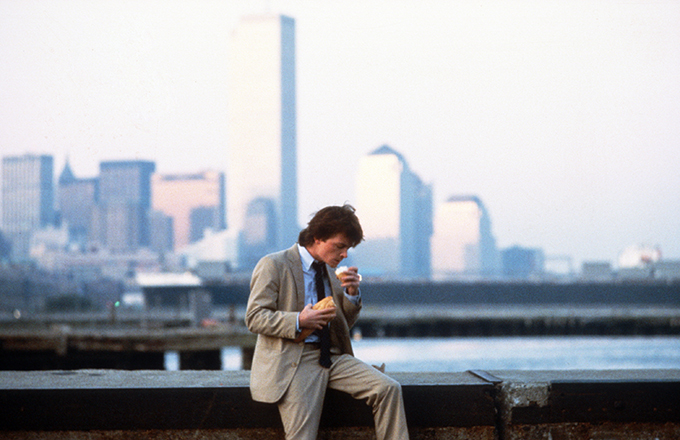

Top Photo: The author in his Greenwich Village penthouse apartment (Chris Sorensen/Redux)

Source link