Carl Fletcher is the wealthy Jewish industrialist and father of three in Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s new novel, Long Island Compromise. His rabbi praises his family as “what our ancestors hoped for us when they abandoned their terrorized homelands and made way for this world.”

It is because of his prominence as a Jewish American, and his successful business, that two men kidnap him in the driveway of his home in the fictional Long Island township of Middle Rock, hold him captive, and demand $250,000 for his release.

For the better part of a week, while handcuffed to an exposed pipe inside a closet, Fletcher faces a barrage of verbal and physical abuse. His kidnappers call him “Jew scum,” “sheeny,” and other anti-Semitic epithets. They threaten Fletcher’s family with gang rape by men of varying racial makeups—Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Arabs. It’s all intended to terrify him.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In a phone call to Fletcher’s wife, one kidnapper identifies himself as a “colonel of the Caliphate Freedom Fighters of the Valley of Palestine.” He claims responsibility for several violent terrorist acts committed against rabbis and Jewish community centers. He threatens Fletcher with a similar fate if his wife, whom he calls “Jew pig,” fails to pay up. Ruth and family do as instructed, delivering a paper bag filled with $250,000 on a baggage carousel inside JFK airport. The kidnappers recover the ransom and, despite the heavy presence of local police and FBI agents, evade capture. Shortly afterward, Fletcher is found outside a gas station, his hands still handcuffed, and his business suit covered entirely in his own excreta.

In a matter of weeks, the FBI arrest two men in connection with the kidnapping: Drexel Abraham, a former employee at Fletcher’s factory who previously spent ten years in prison for a “minor involvement” with a black militia; and Lionel, Drexel’s brother. Both men receive maximum prison sentences, and both die behind bars just years later—Lionel in a prison riot and Drexel from pancreatic cancer.

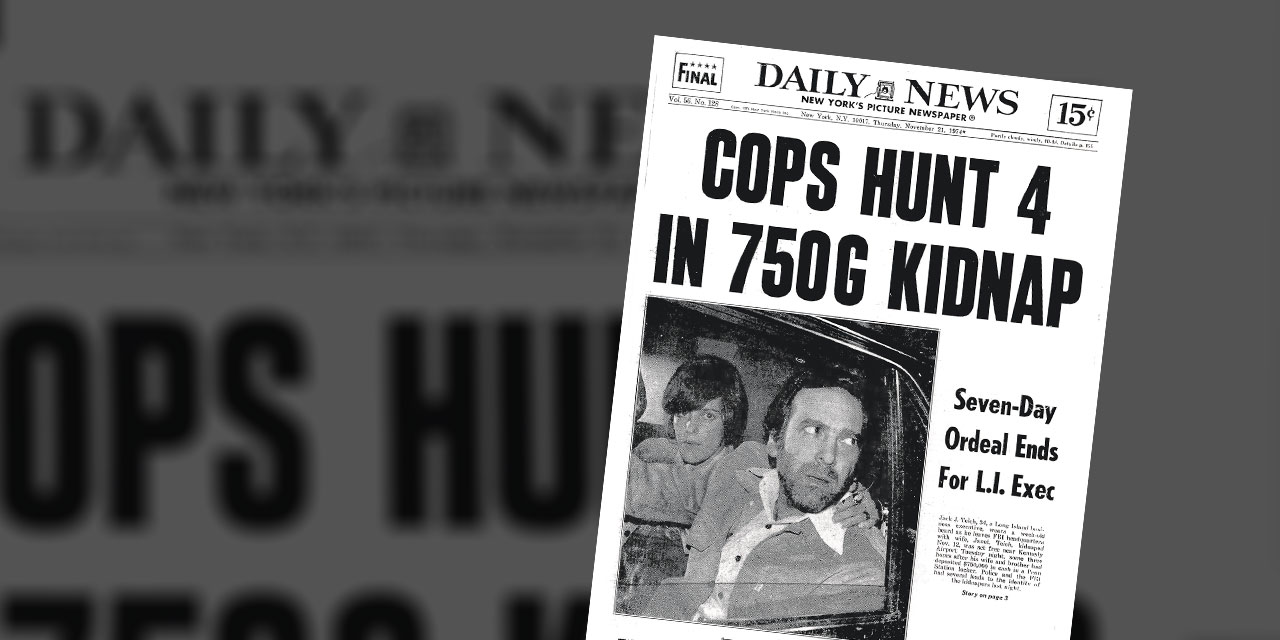

While the story of the Fletchers is the work of fiction, the real-life 1974 kidnapping of Jack Teich, which serves as the basis for Long Island Compromise, and the anti-Semitic and avaricious motivations of the offenders themselves are not. At a time when anti-Semitic attacks and rhetoric are becoming increasingly prevalent, both kidnappings, the real and the imagined, serve as a reminder of the tragic consequences of justifying violence against American Jews in the name of anti-Zionism.

On the evening of November 12, 1974, Teich, a wealthy Jewish businessman from the Long Island village of Kings Point, was kidnapped in the driveway of his home by two men wearing ski masks and carrying firearms. Like his fictional counterpart, Teich worked for his family company—in his case, Acme Steel Partition and Door Company, a steel manufacturer in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

The men forced Teich into the backseat of their car, handcuffing him and blindfolding him with a putty-like substance smeared over his eyes. In Operation Jacknap, his 2020 account of his kidnapping, Teich writes that one of his abductors asked that he confirm that he was Jack Teich and that he was a Jew.

After a long drive to the Bronx apartment where they would hold Teich captive, the men forced him inside a dark closet and fastened chains around his wrists and neck, connected to a closet hook. He was provided a bucket to use as his commode. One man, whom Teich called the “Keeper,” demanded that he tell them everything—the amount of money in his bank account, the profitability of Acme Steel Partition and Door, the value of the mortgage of his house, even the antiques that his family owned.

The Keeper wanted Teich to confess to being a member of the Jewish Defense League, which he was not, and insisted that Teich and the JDL were “going to kill Yasser Arafat,” the leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. The Keeper’s rants against Jews would continue throughout Teich’s captivity. He called Teich a Jew slumlord. He blamed “Jews and the whites” for causing the “plight of the poor people in America, Africa, and the Middle East.” The Keeper set the ransom for Teich’s release at $750,000 ($4.7 million in today’s dollars)—one of the largest in U.S. history.

The Keeper referred to the ransom as Teich’s “fine” that, once paid, would be sent overseas to “feed hungry poor people in other lands. It’s going to help the Palestinians and poor black people.” He tells Teich: “This is going to teach you and your people not to keep all the money for yourselves.” The Keeper struck Teich as being equal parts meticulous and depraved. “He thought through everything he said and did. He knew what he wanted,” Teich writes in Operation Jacknap.

In their ransom note to Janet Teich, Jack’s wife, his kidnappers referred to Teich’s abduction as an “arrest . . . due to crimes against poor people.” They demanded that the family pay his “fine” in full for his release. They signed their ransom note with “Death to racist capitalism.”

The $750,000 would eventually be raised, and Janet and Buddy Teich, Jack’s brother, were instructed to bring a gym bag with the cash to a public phone booth in Times Square. From one call at a different phone booth to the next, Janet and Buddy were finally sent to a public locker near a Long Island Rail Road track in Penn Station, where they placed the money inside and left.

Shortly afterward, an African American male dressed in a “floppy hat” and long coat retrieved the ransom from inside the locker. He boarded a subway train, cash in hand, and evaded capture, despite the presence of 450 federal agents and local police surveilling the area. The authorities didn’t want to apprehend the man, partly because they feared jeopardizing Teich’s life. Complicating matters: the FBI’s radio transmitters failed to work inside Penn Station, and an agent stationed on the Seventh Avenue subway platform did not receive the call that the suspect was headed his way.

Hours later, the kidnappers dropped off Teich, disoriented and disheveled, at a gas station by the Belt Parkway. He was alive and relatively unharmed. Before his release, the Keeper poured Teich a shot of scotch and directed him to “tell your people not to keep all the money.”

“This is a good lesson for you.”

It wouldn’t be until 1976, in Barstow, California, that Richard Warren Williams, a once-successful entrepreneur and Korean War veteran, was arrested in connection with Teich’s kidnapping. The FBI had been monitoring Williams for months, after recovering a $100 bill he had used to pay for his rental apartment. At the time of his arrest, Williams had $10,000 in $100 bills hidden inside a money belt. Authorities discovered an additional $28,000 in cash concealed in Williams’s motor home. The serial numbers on the recovered cash matched those of the ransom money.

Williams made for a surprising—and yet, not entirely surprising—kidnapping suspect. In the 1960s, he was the owner of Ric Williams Realty, a thriving real-estate business that sold homes to blacks and Hispanics in the predominantly white San Fernando Valley. He employed minorities, and at one point his business became “one of the fastest-growing black real estate firms in Southern California,” according to a 1976 Newsday article. His success afforded him a six-figure home, his own plane, and an invitation to teach African American history at California State University, Northridge.

Williams had developed an increasingly radicalized view on race, which had carried over to his business life. He hung photos of Malcom X and Angela Davis in his office, which “scared off” his customers, according to Newsday. He was accomplished and intelligent but had grown increasingly cynical about race relations. “I saw Richard as a principled person who really was committed to relieving blacks from their oppression,” said H. Raymond Fasano, an attorney who would represent Williams in the 1990s. “He was an intelligent guy and calculating. I mean, extremely calculating,” said Edward McCarty, a former Nassau County assistant district attorney who served as prosecutor in Williams’s 1978 trial.

Teich writes that one former employee told investigators that Williams, after his race radicalization, had started carrying a loaded .32 caliber pistol. “Ric said he was proud of being his own boss and that he didn’t have to work for ‘whitey,’ ” said the former employee.

In 1971, Williams moved his family to British Guyana to launch an air-charter business. Frustrated by the country’s socialist oversight on business, he abandoned the venture and returned to California. Around that time, Williams received a phone call from Charles Berkley, a childhood friend who had worked as a draftsman at Acme Steel Door for 15 years, until 1973. Berkley pitched Williams the idea of kidnapping Teich.

Williams’s and Berkley’s eventual execution of Teich’s kidnapping involved “fabulously detailed planning,” said McCarty. “They were extremely careful. They thought of everything,” he added. And for nearly two years afterward, Williams got away with it.

After an 18-week trial, Williams was found guilty by an all-white jury and sentenced to 25-years-to-life in prison. Berkley was indicted for his role in the kidnapping in 1977. He spent three years on the run before turning himself in to a reporter for WNBC-TV. Charges against him were eventually dropped.

In 1994, Williams successfully appealed his conviction by using a 1986 Supreme Court ruling that prosecutors and defense attorneys needed to prove that the dismissal of potential jurors wasn’t racially motivated. Williams’s attorney at the time repeatedly requested to install blacks on the jury, though McCarty used peremptory challenges to dismiss six African American potential jurors.

The New York State Supreme Court overturned Williams’s conviction, ordered a new trial, and released him from prison. Williams, who had maintained his innocence throughout his trial and incarceration, now had a second chance to clear his name. “I am open to a humanistic approach from the district attorney and I am interested in being exonerated,” Williams told reporters after his release.

Ultimately, Williams agreed to plead guilty to reduced charges, including second-degree kidnapping. He decided to take the deal because he wanted to spend more time with his grandkids, said Fasano. “The guy served 20 years. We all felt that was enough.”

Except for the money recovered from Williams’s arrest and a $10,000 donation that Williams made to the Organization of African Unity that was eventually returned to Teich, nearly all the ransom money is missing. Teich still offers a reward for its return. “Nobody has come forward to the Teich family to return their money,” said McCarty.

Both Berkley and Williams are believed to have died sometime in the past decade, McCarty noted.

As for the motivations behind Williams’s crime, Fasano denied that it was because of anti-Semitism. “He never made any anti-Semitic reference to Teich that I can remember,” he said. “He had a proletariat view of Teich. He thought he was greedy. He thought he was an oppressive boss.” McCarty disagreed. “The motivation there was anti-Semitism, among other things,” he observed. In Operation Jacknap, Teich writes that Berkley’s and Williams’s “anti-imperialist and anti-Semitic hate was really just camouflage for a brutal extortion plot.” Teich declined requests for comment.

The Keeper’s anti-Semitic rants seemed to be more than just “camouflage,” however. They were a gateway justification for a more malignant form of anti-Zionism as anti-Semitism, which has reemerged after Hamas’s terror attack on Israel on October 7, 2023. What we’re seeing and hearing today is on par with—and, in many instances, eclipses—the extremism of Williams’s expressed views.

Consider a few recent examples. In October 2024, a 39-year-old Orthodox Jewish man was shot as he was walking to synagogue in the North Side of Chicago. Sidi Mohamed Abdallahi had been following the man, who was wearing a prayer shawl and yarmulke, for several blocks before shooting him in the shoulder. After fleeing the scene, Abdallahi returned a short while later and fired two shots at police and paramedics who were treating the wounded man. Officers fired back, hitting Abdallahi multiple times. Both he and his victim survived. Cell-phone data showed that Abdallahi had been actively searching for Jewish targets, mapping out locations of several Jewish schools and synagogues throughout Chicago prior to his attack.

Khymani James, a Columbia University student, was suspended after recording himself saying that Israel’s existence was “antithetical to peace” and that people “should be grateful I’m not out murdering Zionists.” James sued the school in October, alleging discrimination and violation of his Tedeschi rights.

In June, three protesters vandalized the home of Anne Pasternak, the director of the Brooklyn Museum, covering her home with red paint and hanging a banner calling her a “White Supremacist Zionist.” The trio also defaced the homes of two museum board members with “Jewish-sounding names” while sparing two other board members who did not have Jewish-sounding names, according to Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez. Three people, including Taylor Pelton, an illustrator, and Samuel Seligson, a freelance videographer for Al Jazeera and Fox News, were charged with hate crimes.

Some dismiss anti-Semitism—in America, anyway—as Matt Stoller did on X, claiming that it’s “not a meaningful problem.” The numbers tell a different story: more than 8,873 anti-Semitic incidents occurred in this country in 2023—a 140 percent increase from 2022, according to the Anti-Defamation League.

Kidnapping an innocent Jewish man from his home, threatening his family with gang rape, and stealing $750,000 of his money is not a righteous education, as the Keeper believed. Denude it of its sanctimony, and you will see what the “education” truly was: a criminal act driven by greed and hate. There’s no excuse for such cruelty.

Photo: New York Daily News via Getty Images

Source link