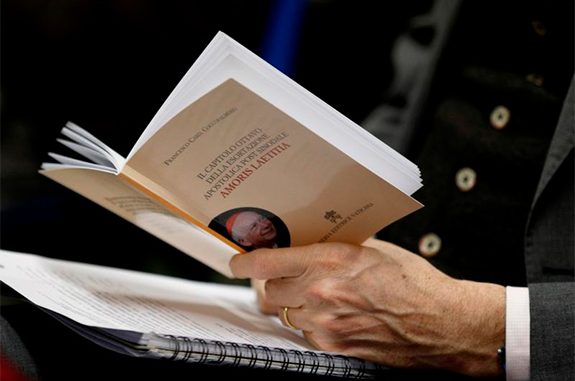

Editor’s note: March 19th marks the ninth anniversary of Amoris laetitia (it was released on April 8, 2016), Pope Francis’s post-synodal Apostolic Exhortation on the pastoral care of families. Since that time, CWR has published several pieces addressing various sections and aspects of the document. The following essay, which is the result of extensive work and thought by two notable moral theologians, considers in detail some essential questions and ongoing concerns about the controversial eighth chapter of the document. This essay is longer and more academic than most CWR pieces, but we believe it is an important contribution to vital theological, moral, and pastoral questions that remain unanswered and debated.

——–

Author’s note: When Amoris laetitia (AL) teaches that some divorced and civilly remarried individuals may rightly receive Holy Communion without resolving to live as brother and sister, is it setting forth merely a pastoral conclusion regarding a purely disciplinary matter or is it teaching something that is primarily a matter of doctrine? And is that teaching consonant with the Catholic faith? We argue that AL’s teaching, while also disciplinary in nature, is primarily a matter of doctrine. After noting that AL never explicitly asserts anything contrary to divine revelation and making a diligent effort to disambiguate the text, we find ourselves faced with the disconcerting question of whether AL implicitly contradicts divine revelation. We then ask the more general question of how theologians and the faithful should respond if they become convinced that a new teaching contradicts a previous infallibly proposed teaching.

———

Chapter eight of the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris laetitia (AL) addresses problems associated with pastoral care for divorced and civilly remarried persons and, in particular, the question of their reception of the Eucharist. The text has been widely interpreted as teaching that it is sometimes morally licit for a pastor to admit divorced and civilly remarried persons living together more coniugale (i.e., as married—sexually active), who are unable to obtain a declaration of nullity, to Holy Communion.1 Pope Francis himself has affirmed the validity of that interpretation by endorsing the Buenos Aires bishops’ pastoral application of AL8.2

We do not disagree with this widely accepted interpretation. But after a careful analysis, we ask whether AL8 does not, problematically, imply more,3 namely, that among the cohort of individuals free to receive, and thus to be admitted to,4 the Holy Eucharist, are some civilly remarried persons living in sexually active second relationships who (1) are still validly married to somebody else;5 (2) understand that their condition of life is contrary to Sacred Scripture and Church teaching; and (3) though capable of changing their situations, are unwilling to change because they would find doing so extremely difficult.6 In what follows, our use of the term more coniugale should be understood as including those who meet this trifold description.

AL does not explicitly assert all of these things. But the absence of explicit assertions leaves the impression that at least some who fit this description fall within the cohort of persons who can rightly receive the Holy Eucharist. The question arises as to whether AL through the use of ambiguous language teaches that some who live more coniugale may receive Holy Communion. We are by no means unique in noticing problems that arise from the text’s ambiguous language.7 Indeed, the fact that the pope himself has had to emphasize certain interpretations as consistent with his meaning suggests that even he acknowledges the problem of the misunderstanding of his text.

In order to get a handle on the meaning of AL8, it will be necessary to show both what the ambiguities are and why the generally accepted (and apparently papally-endorsed) interpretation is that some who live more coniugale may receive the Eucharist.

If this interpretation of AL8 is correct, it follows that the chapter implicitly contradicts at least one of the following revealed truths: (1) no one should receive the Eucharist without being willing to conform his or her life to the objective demands of the Gospel; (2) a consummated Christian marriage is absolutely indissoluble;8 (3) for a married person to have sex with someone other than his or her valid spouse is always adulterous;9 or (4) adultery is always gravely wrong.

It is important to note that AL does not explicitly deny any of these truths, and we do not want to minimize, much less do away with, the difference between implicitly contradicting and explicitly denying a truth of faith. We think that difference is quite significant, for the latter would be formal heresy, and we are not making any such accusation. We think it likewise should be noted that AL explicitly affirms—and does so repeatedly—one of those doctrines, namely, the indissolubility of marriage.10

We agree with Matthew Levering that an explicit contradiction of a truth of faith would have disastrous consequences for the faithful with respect to their ability to trust teachings promulgated as magisterial.11 Someone might argue that since we acknowledge that AL does not explicitly deny a truth of faith, we should avoid asking whether it does so implicitly because raising this question may unnecessarily open a can of worms and shake the faith of believers. Better, the argument continues, to open that can only in the unlikely event of a pope’s explicit denial of a truth of faith.

This line of thinking is understandable, because questioning whether a papal document is inconsistent with a truth of faith can make it harder for the faithful to trust teachings promulgated as magisterial, and those previously unaware of any difficulty may be disturbed. It might therefore seem better to avoid drawing attention to the situation and trust that if there is a problem, it will be fixed by later magisterial teaching reaffirming the truth of faith in question.

However, implicitly contradicting a truth of faith also has very serious consequences for the faithful. It too undermines the credibility of magisterial teaching. In the present case, it would cause scandal not only by leading some who conclude that AL contradicts a truth of faith to deny that truth, but also by making it easier for validly married members of the faithful to rationalize entering into (or remaining in) more coniugale relationships. It would also cause disunity among the faithful between those who affirm and those unwilling to affirm the truth of faith in question. Moreover, we should not assume that if there is a problem, subsequent magisterial teaching will resolve it in the near future. Meanwhile, people in irregular marital situations will undergo harm, for even if their subjective culpability is mitigated, there remains an objective lack of conformity between their activity and their good.

If a teaching promulgated as magisterial contradicts a truth of faith, it behooves theologians to point this out and to consider how they, the faithful, and the Church’s pastors should respond to this problem. Of course, theologians who argue that the teaching of such a document implicitly contradicts a truth of faith may be mistaken, and if they are, it would be a service to them and the Church for this to be made clear. But far from being unfaithful or ill advised to raise the question, it is important to do so, for if a problem exists, it should be dealt with. We think that there is sufficient warrant to raise the question with respect to the teaching of AL8, and we would welcome a response that could show that our concerns are misplaced.

To explicate the meaning of AL8 we identify and analyze ten ambiguities found there. However, in order to properly deal with the question of Holy Communion for those living more coniugale, it will be necessary first to resolve the question of whether the document’s directives are disciplinary or doctrinal.

Discipline or Doctrine?

The question of whether certain matters treated in AL8 pertain to doctrine or only to discipline is obscured through the persistent use of ambiguous language. This is the case with its treatment of the question of whether persons living more coniugale may receive the Eucharist, a question which is refracted through the perspective of the priest. AL frames that question in terms of whether pastors may “admit” these individuals to the sacraments,12 as if the question is purely a disciplinary matter to be settled as the priest discerns it should be. But the priest will have a determining judicial role only if more coniugale cases are not, as we contend they are, settled a priori by doctrine.

Of course, some will deny that this matter is settled by doctrine and insist that it indeed is a purely disciplinary matter. After all, John Paul II refers to the Church’s traditional exclusion of these individuals from the Eucharist as a “custom/practice/discipline” (consuetudinem),13 and that discipline openly seems to rest on what looks like a prudential judgment about what would confuse and scandalize the faithful.14 But neither of these objections demonstrates that the question is not settled a priori by doctrine. Though John Paul refers to the traditional exclusion as a discipline, he goes on to assert that the discipline “is based upon Sacred Scripture”; and he identifies as a reason for excluding these individuals not only the risk of scandal, but more importantly, the fact that “their state and condition of life objectively contradict that union of love between Christ and the Church which is signified and effected by the Eucharist.”

We acknowledge that this matter does pertain to Church discipline. It should be noted, however, that some disciplinary matters are settled a priori by doctrine. All disciplines direct action, but in some cases, a choice contrary to a Church discipline entails at least an implicit contradiction of doctrine. We are asking whether the matter at hand is such a case. To hold that individuals living more coniugale—i.e., in sexually active second relationships despite being validly married to somebody else, who understand that their life-state conflicts with Sacred Scripture and Church teaching, and who are unwilling to live as brother and sister because they find this very difficult—can rightly receive Holy Communion raises the question, noted above, of whether that teaching implicitly contradicts a doctrine of the faith. Therefore, what is at stake in the question of the reception of the Eucharist by the divorced and civilly remarried is first and foremost a matter of doctrine.

It is important to see that the relevant subject of this whole discussion is not the priest, but the penitent/would-be-communicant, who can rightly make a judgment of what he or she should do only by following the objective doctrinal criteria, which the priest should help the person understand. From the point of view of the would-be-communicant (or penitent), there is only one perspective: subjective, for he or she should ask, what should I do? But this question logically entails an objective standard on which to base the judgment of what to do—that is, the question can be answered only with reference to one’s objective condition. Thus, one must ask: Is it wrong for me to receive Holy Communion if I am having sex with someone to whom I am not validly married? For that reason, and to make it clear that doctrine and not just discipline is at stake, we will frame the question in terms of whether a person should receive the Eucharist, and speak of admitting a person to the Eucharist only secondarily.

First ambiguity: Must these individuals commit themselves to sexual continence before receiving Holy Communion? (AL 298)

The text reads: “The Church acknowledges situations ‘where, for serious reasons, such as the children’s upbringing, a man and woman cannot satisfy the obligation to separate.’” Appended to that passage is footnote 329, which reads:

John Paul II, Apostolic Exhortation Familiaris Consortio (22 November 1981), 84: AAS 74 (1982), 186. In such situations, many people, knowing and accepting the possibility of living “as brothers and sisters” which the Church offers them, point out that if certain expressions of intimacy are lacking, “it often happens that faithfulness is endangered and the good of the children suffers” (Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et Spes, 51).

The text and footnote are full of ambiguous suggestions and seem to imply that individuals living more coniugale need not always refrain from sexual relations. These passages introduce the unique pastoral category of divorced and civilly remarried persons who have judged that for the good of children they “cannot satisfy the obligation to separate,” and believe that living “as brothers and sisters” (i.e., adopting perfect continence) may be harmful to the children. But why introduce this cohort? Given what follows in the document, it seems clear that the reason is not to encourage pastors to help these people adhere to the Gospel’s saving command to all non-married persons to live in perfect continence, so that they will be properly disposed to receive Holy Communion. Rather, it seems that the cohort is being considered with a view to admitting them to Communion without adhering to that moral requirement.15 And what about the expression “faithfulness is endangered”? Surely it is misleading. We are dealing with an objectively adulterous union to which no one should be faithful.16 AL 298 says earlier that because these individuals express “proven fidelity” and “Christian commitment,” they “should not be pigeonholed or fit into overly rigid classifications.” But “fidelity” and “commitment” here can be understood at best only in an extremely narrow sense. They do refer to being faithful to a commitment, but to one that should not have been made because it violated and continues to violate an earlier commitment to one’s valid spouse. It is difficult to see how a commitment that violates Christ’s teaching that those who divorce their valid spouse and marry another commit adultery can be reasonably regarded as a Christian commitment.

Additionally, the use of the Gaudium et spes (GS) quotation in the context of John Paul II’s words in Familiaris consortio (FC) suggests that GS supplies a reason for concluding that living more coniugale can in this case be morally legitimate. But that conclusion is the polar opposite of John Paul’s teaching: “when, for serious reasons, such as for example the children’s upbringing, a man and a woman cannot satisfy the obligation to separate, they ‘take on themselves the duty to live in complete continence, that is, by abstinence from the acts proper to married couples’” (emphasis added).

Footnote 329 also suggests that GS 51 is relevant to problems of intimacy between divorced and civilly remarried persons. But GS does not address these persons—not in no. 51, not anywhere. Nor, a fortiori, is it addressing ethical problems related to their intimacy. The quoted text is addressing short-term abstinence chosen by persons who are validly married in their “responsible transmission of life.” GS considers this matter not to raise doubts about traditional moral requirements of marital chastity, but rather to reaffirm the ancient teaching that these people should not adopt the “dishonorable solutions” of contraception or abortion.

Further, AL 298 speaks of “the great difficulty of going back [to one’s first marriage] without feeling in conscience that one would fall into new sin.”17 This problematically suggests that the difficulty of staying faithful to one’s first marriage could justify remaining in an objectively adulterous relationship as a way of avoiding falling into further sin.18 It is as if charity itself demands that one maintain a lifestate contrary to the commandments.19

And just what does “feeling in conscience” mean? One might feel that one would fall into new sins if one were to return to one’s first spouse. But conscience is not a matter of feeling but of judging. One can never come to an accurate judgment that one would fall into new sins if one follows the moral law unless one is unwilling to rely on God’s grace—in which case, the problem is not one’s inability to avoid new sins, but one’s unwillingness to cooperate with grace.

Finally, AL 298, quoting FC 84, refers to “those who…are sometimes subjectively certain in conscience that their previous and irreparably broken marriage had never been valid.” AL’s use of this text suggests a conclusion that the Church has never taught—that this certainty alone might justify these individuals living in a sexually active relationship. However, if people’s judgment about the invalidity of their first marriage is true, they have an obligation to do what they can to show in the external forum that their first marriage was invalid and to have their second union recognized by the Church as a marriage.20 Otherwise, even if the person’s judgment about the invalidity of the first marriage is true, so that the sexual activity in the second union is not adultery, nevertheless that sexual activity would be fornication.

Second ambiguity: Does no easy recipes mean no refusal of the sacraments? (AL 298)

No. 298 is devoted to explaining complex situations in which the divorced and civilly remarried find themselves. The last two sentences of the section read: “The discernment of pastors must always take place ‘by adequately distinguishing’ [note omitted], with an approach which ‘carefully discerns situations’ [note omitted]. We know that no ‘easy recipes’ exist.333”

Other than to remind pastors of the obvious fact that not all situations are alike, the purpose for the strong admonitions to distinguish and discern is ambiguous. It is ambiguous because although situations are dissimilar in some respects, they are similar in one critically important pastoral respect. Because all are instances of putatively valid marriages breaking down and new relationships being taken up, all of them have in common that sexual activity in these new relationships would involve grave matter.21 This is the basis of the Catholic Church’s frequent reaffirmation of the exclusion of such individuals from Holy Communion.22

What then does “no easy recipes” mean? It is obviously true that it is not always easy to accept the Church’s teaching that no one living in a more coniugale relationship should receive Holy Communion. But it is hard to avoid the impression that the intended meaning is that accepting this teaching is itself an “easy recipe” that should be rejected.

In this context, the use of footnote 333 is problematic. The footnote references a question-and-answer session held with Pope Benedict XVI during the World Meeting of Families in 2012.23 One questioner tells the pope that some divorced and remarried persons feel discouraged because they are excluded from the sacraments. AL quotes the final words of Benedict’s sympathetic reply: “And we do not have simple solutions.” The full positive meaning of Benedict’s statement is not clear. But we know what he does not mean. He certainly does not mean there is no simple solution to the question of whether these people may be permitted to receive the sacraments, since he says twice in his brief response that they “cannot receive” (“it is not possible to receive”) absolution or the Eucharist. AL, it seems, is using Pope Benedict’s text to support an ambiguous suggestion that he in fact rejects.

Third ambiguity: Does the logic of integration require overcoming the exclusion of these individuals from Eucharistic communion? (AL 299)

The text discusses the “logic of integration” as the “key to pastoral care” for the divorced and civilly remarried. These individuals, it teaches, need to be helped to realize that the Spirit gives them gifts with which to serve the Church “for the good of all.” Which among the “different ecclesial services” does the text envisage? It mentions four areas: “the liturgical, pastoral, educational and institutional.” One naturally wonders what the logic of “liturgical” integration implies for these people with respect to the traditional denial of eucharistic communion. AL 299 does not yet supply an answer. But it continues to lay down ambiguous hints. It says their ecclesial participation “necessarily requires discerning which of the various forms of exclusion currently practiced, can be surmounted” (emphasis added). Why appropriate integration for the divorced and civilly remarried necessarily requires overcoming currently practiced forms of exclusion, again the text does not say. But since the most conspicuous form of liturgical exclusion is of these individuals from the Eucharist, the hint is clear.

Another hint is evident in the paragraph’s assertion that people in more coniugale relationships “need to feel not as excommunicated members of the Church, but instead as living members.” This statement is misleading. Although these people do not incur the formal penalty of excommunication, they are only living members of the Church if they are invincibly ignorant or incapable of exercising their free will. It is not good for a person in such relationships, or indeed for anyone, to feel that he or she is a living member of the Church unless that person is a living member. Of course, people in such relationships should be welcomed and cherished by the Church, and helped to take the steps necessary to receive the great grace of having their situations rectified so they can once again become living members, and so, too, feel themselves to be such. But this is hardly the obvious interpretation; indeed, the text gives no indication that it has this in mind.

It is worth noting that both John Paul II and Benedict XVI also discuss the importance of ecclesial integration for the divorced and civilly remarried.24 In those discussions they not only reaffirm the traditional exclusion from the sacraments, but they ground the exclusion in the teaching of divine revelation. This is markedly different from AL’s treatment of ecclesial integration.

Fourth ambiguity: Can a priest responsibly discern that God sometimes wants people living in more coniugale relationships to receive Holy Communion? (AL 300)

AL 298, as noted above, discusses the topic of the discernment of the parish priest in the lives of divorced and civilly remarried Catholics. AL 300 continues this discussion, focusing upon complexities in their practical situations:

If we consider the immense variety of concrete situations …, this Exhortation could [not] be expected to provide a new set of general rules, canonical in nature and applicable to all cases.25 What is possible is simply a renewed encouragement to undertake a responsible personal and pastoral discernment of particular cases, one which would recognize that, since ‘the degree of responsibility is not equal in all cases’ (note omitted), the consequences or effects of a rule need not necessarily always be the same.336

Footnote 336 reads: “This is also the case with regard to sacramental discipline, since discernment can recognize that in a particular situation no grave fault exists.”

The text introduces several ambiguities. First, it suggests that it is possible to discern responsibly that sometimes God wants someone living in a more coniugale relationship to receive Holy Communion; and by using the term “renewed,” the text further suggests that responsible pastors have already been engaging in such discernment. It should be noted, however, that discernment about what God wants can only properly take place after one has identified and eliminated possibilities that one should already know that God cannot possibly want—which is to say, it is only possible to engage in responsible discernment about morally good or indifferent options.26 AL suggests that in some cases it would not be wrong but rather good for the divorced and civilly remarried to receive Holy Communion, and that admitting them would therefore be the proper pastoral response. But the Church has traditionally affirmed the norm excluding the divorced and civilly remarried from the Eucharist because she has judged that it would be morally wrong for them to receive it.

A further problem arises here. Among the reasons we gave at the outset for holding that individuals living more coniugale should not receive the Eucharist is that rightly receiving it requires the willingness to cease living in that way and to conform one’s life to the objective demands of the Gospel. Another reason we gave is that a consummated Christian marriage is absolutely indissoluble. However, the statement “discernment can recognize that in a particular situation no grave fault exists” leaves the impression that if a pastor judges that a person is not culpable, his pastoral responsibility is to admit the person to Holy Communion rather than to help him or her see that no one should live in a more coniugale relationship, and that those unwilling to extricate themselves from such relationships should not receive the Eucharist.

It should first be noted that the traditional eucharistic exclusion has never been conditioned upon subjective culpability. Although persons living in such relationships may be inculpable, the Church teaches that their “state and condition of life objectively contradict that union of love between Christ and the Church which is signified and effected by the Eucharist,” and if such persons were admitted to Holy Communion, “the faithful would be led into error and confusion regarding the Church’s teaching about the indissolubility of marriage” (FC 84). Cardinal Gerhard Müller elaborates the reasoning for the Church’s Eucharistic discipline:

The principle is that no one can properly will [“wirklich wollen”] to receive a Sacrament—the Eucharist—without at the same time having the will to live according to all the other Sacraments, including the Sacrament of Marriage. Whoever lives in a way that contradicts the marital bond opposes the visible sign of the Sacrament of Marriage. Concerning his bodily existence, he makes himself the “countersign” of indissolubility, even if he is not subjectively at fault. Precisely because his life in the body is opposed to the sign, he cannot participate in the supreme sign of the Eucharist—in which the incarnate Love of Christ is manifest—by receiving Communion. If the Church were to admit him to Communion, she would then be committing what Thomas Aquinas calls ‘a falsity in the sacramental signs.’ This is not an exaggerated conclusion of doctrine, but the very basis of the sacramental constitution of the Church, which we have compared to the architecture of Noah’s ark. The Church cannot change this architecture which comes from Jesus himself, because the Church originates here and relies on it (this sacramental constitution) to navigate the waters of the Flood. To change the discipline on this particular point and to permit a contradiction between the Eucharist and the Sacrament of Marriage would necessarily mean changing the Church’s Profession of Faith. The blood of the martyrs has been shed over belief in the indissolubility of marriage—not as a distant ideal, but as a concrete way of acting.27

Moreover, AL’s footnote 336 may be understood to mean that a pastor can judge that someone committing objectively and gravely wrong acts is not at fault for those acts. Even if the traditional exclusion were conditioned upon culpability, it should be noted that a pastor’s ability to judge that someone who is living more coniugale is not culpable for mortal sin is extremely limited. He may think it likely, or even highly likely, that a person living in such a relationship is not culpable. But it is not clear how the pastor can have moral certitude about that unless he knows that the person is either incapable of consent or unaware of the moral truth governing his or her non-marital situation.

Finally, to strengthen the case for returning the divorced and civilly remarried to the sacraments, footnote 336 references Pope Francis’s 2013 Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii gaudium, which states that “the doors of the sacraments” should not “be closed for simply any reason.” It continues:

The Eucharist…is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak. These convictions have pastoral consequences that we are called to consider with prudence and boldness. Frequently, we act as arbiters of grace rather than its facilitators. But the Church is not a tollhouse; it is the house of the Father, where there is a place for everyone, with all their problems.

It is true, of course, that pastors should devote themselves to facilitating the reception of grace, and that they should not exclude people from the Eucharist for just any reason. But in context, the statement suggests that pastoral charity, prudence, and boldness require admitting couples living more coniugale to the Eucharist.

Fifth ambiguity: Does proper accompaniment of those living in more coniugale relationships mean they should be free to receive Holy Communion? (AL 300)

After discussing the Church as a “place for everyone,” the document exhorts priests to “accompany the divorced and remarried in helping them to understand their situation according to the teaching of the Church.” This “process of accompaniment and discernment…guides the faithful to an awareness of their situation before God.” AL 300 then says:

Conversation with the priest, in the internal forum, contributes to the formation of a correct judgment on what hinders the possibility of a fuller participation in the life of the Church.… This discernment can never prescind from the Gospel demands of truth and charity, as proposed by the Church.

If we take the text at face value, it lays down three sound principles of priestly accompaniment for divorced and civilly remarried persons: first, help them come to an understanding and awareness of their moral situation before God; second, help them form their consciences on what hinders full participation in the life of the Church; and third, ensure that this process is guided by the teaching of the Gospel as proposed by the Church.

However, unless we ignore what the document says elsewhere, this passage cannot be taken at face value. This is because a central truth of the Gospel (and Church teaching) relevant to these people’s spiritual welfare is that sex with someone other than one’s valid spouse is always gravely immoral. What exactly is necessary to ensure not only that the process does not prescind from the Gospel demands of truth and charity as proposed by the Church, but also that these individuals have a salutary understanding of their situation before God and are able to form their consciences correctly? Accompaniment should at least guarantee that they unambiguously know that it is wrong for anyone living more coniugale to receive Holy Communion, and should establish as a condition for their return to the Eucharist that they cease living in that way. However, as noted above, AL suggests that a priest might rightly discern that God wants someone living in such a relationship to receive Holy Communion.

We said above that individuals living more coniugale should, like everyone else, not receive the Eucharist if they are unwilling to conform their lives to the objective demands of the Gospel. But the question again arises about those in whom “no grave fault exists” (footnote 336). We saw above that the text considers divorced and remarried persons who may not be subjectively culpable for the sin of adultery. Should the priest then approve of their reception of the Eucharist? Again, the traditional eucharistic exclusion has never been conditioned upon subjective culpability. Still, it is worth noting that the text’s ambiguous treatment of inculpability confuses the question. To be inculpable, these persons must either lack sufficient reflection about the wrongness of their adultery or be incapable of avoiding it, or both.

AL 300 itself gives us reason to believe that individuals who have gone through the process of accompaniment do not lack sufficient reflection. For if that process aims at correct conscience formation and can never prescind from the demands of the Gospel, then after adequate formation has taken place, the inculpability that arises from lack of sufficient reflection ordinarily may be presumed to be overcome. Of course, a person who knows the Church teaches that living in a more coniugale relationship is gravely wrong, and who is capable of exercising free will, might reject that teaching without culpability because he has a blameless erroneous conscience that leads him to think that it is morally permissible for him to do so. But such a person has to that extent separated himself from full communion with the Church. While God is perfectly capable of bestowing grace in other ways,28 the person should not expect to receive it through the channels intended for those whose lives are in harmony with what the Catholic Church understands the Gospel to require, and so should not receive Holy Communion.

Does the text mean that such individuals are inculpable because they are incapable of exercising free will to change their behavior? Even admitting that some may be incapable, how can a priest adequately distinguish between incapability and unwillingness? To assess the measure of a will’s capacity for choice, other than in cases of manifest mental incapacitation, is extremely difficult if not practically impossible.

Can a priest who knows that a person is objectively committing adultery ever be sure that the individual is innocent with respect to that behavior? The priest may think it highly likely that the person is innocent, but what if his judgment is wrong? The worst possible response would be to give such persons the impression that they are right with God and receiving Communion worthily rather than doing what St. Paul strongly warns against, namely, eating and drinking to their own condemnation (see 1 Cor 11: 27–29). Priests therefore should make every effort to enlighten the consciences of such people to know the truth of their objective situation and then sincerely offer them assistance to bring their relationships into conformity with the Gospel. However, AL neither proposes such a pastoral approach nor manifests an awareness of the possibility that a priest’s assessment of subjective culpability may be mistaken and have disastrous consequences.

Sixth ambiguity: Is the requirement of marital fidelity a mere rule or an essential condition for true marital communion? (AL 301–302)

The text continues discussing subjective culpability. Some of what it says is traditional, for example, that moral responsibility for an action may be diminished by factors such as ignorance, duress, fear, and habit; and that even if one is in an “objective situation” contrary to God’s law, this does not imply that one is morally culpable.

But the text says more, and what it says leaves crucial questions unanswered. It adds: “Hence it can no longer simply be said that all those in any ‘irregular’ situation are living in a state of mortal sin and are deprived of sanctifying grace. More is involved here than mere ignorance of the rule.” There are three ambiguities here.

First, neither Catholic teaching nor sound moral theologians have ever said “simply” or otherwise that all persons in second civil marriages are culpable for mortal sin. The Church teaches repeatedly, as we have shown, that the “state or condition” arising from their attempted remarriage after divorce from what is presumed to be a valid marriage objectively contradicts God’s law.29 AL seems to set up a false dichotomy between a straw-man rigorist position and AL’s ostensibly more merciful position.

Second, to say that “more is involved” in mortally sinning than “mere ignorance of the rule” does not adequately account for the seriousness of moral ignorance. Even adultery committed in ignorance results in great harm to both the adulterers and others. The adulterers contradict the “great mystery” (magnum sacramentum) of Christ’s love for his Church that marriage signifies (Eph 5:32). Their failure to bear personal witness to marital fidelity supports a culture of disregard for marriage, and their children are all too often badly scarred and unjustly neglected. In addition, should they receive Holy Communion, their example could easily cause scandal by making divorce appear legitimate and would undermine the Church’s witness to the indissolubility of marriage.

Finally, the text here as elsewhere refers to the Sixth Commandment excluding adultery as a “rule.”30 This, however, is the language of legalism. Rule in this context suggests that this Commandment is not concerned in the first place with moral truth but is merely a matter of positive law. It makes the commandment appear as a restrictive imposition that can unreasonably limit freedom and flourishing, rather than as a basic condition for marital communion, love of self and neighbor, and ultimately salvation.31 The text’s language makes it difficult for the reader to grasp the spiritual crisis in which the divorced and civilly remarried find themselves. Indeed, such legalistic language obscures the moral seriousness of the situation from the couples themselves.

Seventh ambiguity: Does intense struggle exempt one from the moral law? (AL 302)

Extending yet further its discussion of mitigated culpability, the text says that “under certain circumstances people find it very difficult to act differently.” It continues:

Therefore, while upholding a general rule, it is necessary to recognize that responsibility with respect to certain actions or decisions is not the same in all cases. Pastoral discernment, while taking into account a person’s properly formed conscience, must take responsibility for these situations. Even the consequences of actions taken are not necessarily the same in all cases.

Nobody doubts that people frequently find it difficult to act differently. But the fact that the moral law is sometimes very difficult to follow does not imply that one is ever free from the grave obligation to follow it. AL 301 notes that “Saint Thomas Aquinas himself recognized that someone may possess grace and charity, yet not be able to exercise any one of the virtues well.” In context, this suggests that Thomas thinks that if someone finds it very difficult to exercise a virtue, he or she might be exempt from doing so and still remain in grace and charity. But Thomas is replying to an objection that refers to those who perform works of virtue, albeit with difficulty—“Now many have charity, being free from mortal sin, and yet they find it difficult to do works of virtue”; “sometimes [people with] the habits of moral virtue experience difficulty in their works”32—not to those who do not perform them because they find them “very difficult”; and he teaches that those who perform them despite the difficulty are the ones who “have charity” and are “free from mortal sin.”33 But AL 302 suggests that people who struggle with the Sixth Commandment may not be required to keep the moral law of perfect continence, and might still possess grace and charity even if they do not.

The text says that “responsibility” for “certain actions” is “not the same in all cases”; “actions” here includes sexual activity even in more coniugale relationships. The text leaves the impression that in some cases, a person might not have the responsibility to refrain from this sexual activity.34 But since the norm against non-marital sex acts constitutes an exceptionless precept of divine and natural law,35 all who are able to follow it have a grave responsibility to do so. Moreover, the Council of Trent infallibly teaches that it is always possible for a person who is justified and constituted in grace to keep the commandments of God.36 What then are we to say about a person who is able to follow the Sixth Commandment—and Trent requires us to hold that one is always able to follow it with the grace that God never fails to give those who ask him—but freely consents to a violation of that commandment? His difficulty in following it might well reduce his culpability (“responsibility…is not the same in all cases”), but it will not reduce it to the point of making the sin less than mortal, since the three conditions for mortal sin—grave matter, deliberate consent, and sufficient reflection—are met. However, AL 302’s statement, “under certain circumstances people find it very difficult to act differently,” suggests that a sin will not be mortal if a person finds it very difficult to avoid. It is not clear how this can be reconciled with the teaching of Veritatis splendor, which holds up the example of those who accepted martyrdom—is there anything more difficult than that?—rather than violate the moral law.37

Finally, what does it mean to say that “the consequences of actions taken are not necessarily the same in all cases”? This statement suggests that divorced and remarried individuals who find it very difficult to live as brother and sister are sometimes exempt from the traditional exclusion from the Eucharist. We have already shown that the application of that norm is not conditioned upon culpability. But even if it were, how would a pastor assess culpability? The text itself directs pastors to properly form the consciences of these individuals. If pastors do so, should they not presume the condition of sufficient reflection has been met? Are they not then obliged to assist these people to live—to put into practice—what they know to be true?

Eighth ambiguity: Can a sound judgment of conscience ever excuse a person from following the moral law? (AL 303)

According to Catholic theological tradition, conscience is paradigmatically our last and best judgment about what I should do here and now.38 As it is our final and best judgment, it is morally decisive; it binds us to act in accord with it.39 Frequently, a judgment of conscience, given our own deficiencies in general moral knowledge—deficiencies which may or may not be culpable—is imperfect or erroneous. Even so, because conscience’s judgment is our last and best, it binds. The perennial pastoral praxis has been to enlighten such consciences to ensure that their judgments are true and direct action in accord with what is good. This last point is decisive for understanding conscience: its sole role is to direct human action in accord with what is good and ultimately in accord with God’s will.

AL8’s account of conscience is different from the one above and seems incompatible with it. No. 303 begins as follows:

Recognizing the influence of such concrete factors [that mitigate moral responsibility], … individual conscience needs to be better incorporated into the Church’s praxis in certain situations which do not objectively embody our understanding of marriage. Naturally, every effort should be made to encourage the development of an enlightened conscience, formed and guided by the responsible and serious discernment of one’s pastor.

The meaning of the text is not clear, but in context the first sentence suggests that a pastor can discern that individuals living more coniugale are in good faith, and so can feel justified in leaving them in that apparent state and admitting them to Holy Communion. We argued above that it is no easy task for a pastor to attain moral certitude that a couple is in good faith. But even if he could be morally certain, he could not rightly endorse their reception of the Eucharist because, again, the Church’s traditional exclusion is not conditioned on moral culpability.40

Ironically, if the second sentence (“every effort should be made to encourage the development of an enlightened conscience”) were taken at face value, pastors would never be justified in leaving someone in good faith. Indeed, this sentence leads us to expect the text to go on to affirm that anyone who realizes that his lifestyle is objectively and gravely contrary to the teaching of the Gospel is required as a condition for full participation in the sacraments to repent, cease doing evil, and resolve to do good.

AL 303, however, says quite the opposite. The text continues:

Yet conscience can do more than recognize that a given situation does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel. It can also recognize with sincerity and honesty what for now is the most generous response which can be given to God, and come to see with a certain moral security that it is what God himself is asking amid the concrete complexity of one’s limits, while yet not fully the objective ideal.

This statement raises serious concerns. For one thing, objective ideal suggests that what is at stake is only an ideal rather than the infallibly taught moral norm that sex outside of valid marriage is always gravely wrong. If this norm is at stake, then to say that remaining in an objectively adulterous situation “is the most generous response which can be given to God” would contradict Trent’s defined teaching that God always offers people the grace to live according to the moral law.41 No free moral agent ever has limits that make living according to the moral law impossible.

It is worth noting that such a claim would also contradict AL’s own statement in no. 295 that “the law is itself a gift of God which points out the way, a gift for everyone without exception; it can be followed with the help of grace.”42 It is by no means clear how that statement can be reconciled with the supposition that these individuals cannot give to God the more generous response of avoiding adultery. Indeed, the only way to avoid concluding that the document is claiming, pace Trent, that God does not enable these individuals to avoid adultery is to conclude instead that although their sexual activity “does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel,” it cannot reasonably be regarded as adulterous. This interpretation would explain why fidelity to marriage is called an “ideal” and why the text never explicitly calls the sexual activity of these individuals adulterous.

It should also be noted that by acknowledging that these individuals “recognize that [their] given situation does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel” (emphasis added), AL implies that they meet the condition of sufficient reflection. Could the meaning be that these people do not meet the condition of deliberate consent? For that to be the case, their situation would have to be like that of those who suffer from sex addiction or some other mental illness—that is, they would have to be powerless to change their behavior despite being aware of its wrongness and destructiveness. This interpretation is consistent with an earlier passage in AL 301, which referred to the “concrete situation” of these individuals as one “which does not allow him or her to act differently” (emphasis added). If this interpretation is accurate, and their behavior is truly addictive, they would be unable to refrain from sexual activity. But this interpretation raises its own concerns. Since addicts can and do resolve all the time to undertake steps with a view to changing their self-destructive behavior, why does the text, following Church teaching (e.g., FC 84), not require that these individuals do the same, and thus at least resolve to live perfect continence, however much they might struggle to be faithful to that resolution? And why does the text not admonish pastors to assist them in their difficult journey to live a life of probity in relation to the Sixth Commandment? The absence of such requirements and warnings suggests that the text does not mean that these individuals are incapable of changing their situations, but rather that they are not morally obliged to try to do so.

However we interpret AL’s teaching on conscience in no. 303, one of three conclusions seems inevitably to follow: that with God’s grace, one is not always able to avoid adultery; that a married person who has sex with someone other than his or her valid spouse does not always commit adultery; or that adultery is not always gravely wrong.

Ninth ambiguity: Does the norm against adultery admit of exceptions? (AL 304–305)

By appealing in an ambiguous way to a well-known teaching of Aquinas, AL 304–305 suggests that there are no exceptionless moral norms, negative or otherwise, including the norm against adultery. Aquinas teaches that when we move from general moral principles to their practical application in concrete matters, the general principles are sometimes “found to fail,” meaning they do not bind in all situations.43 Applying this to divorced and civilly remarried persons, AL teaches that pastors “cannot feel it is enough simply to apply moral laws to those living in ‘irregular’ situations, as if they were stones to throw at people’s lives.”

This can be read in two ways: the first, as saying it is not enough to apply the moral norm against adultery to these individuals; in other words, more than following it may be required. The second says that pastors cannot simply apply the norm to them, meaning—ostensibly following Aquinas—there are cases where the norm against adultery is itself “found to fail”; in other words, what is required is less than following the general moral norm. In context, readers will surely understand the text in the second way.44

Although Aquinas does indeed say that in concrete situations, moral truth does not always bind identically for all, the moral truth he uses as an example is the positive norm, which admits of exceptions, that we ought to return items lent to us in trust when their owners request them. Aquinas says, “this is true for the majority of cases.” He goes on to say, however, that if in a particular case it would be harmful to return the items—say, for example, “they are claimed for the purpose of fighting against one’s country”—then we ought not to return them. In this situation, the positive (affirmative) norm yields to an exception. But its yielding is based on the requirements of protecting human goods, the same human goods that require unqualified protection against acts wrong in themselves, acts which are singled out and excluded by more fundamental negative moral norms, which do not yield to exceptions. Aquinas is very clear on the distinction between positive norms, subject to exceptions, and the exceptionless nature of negative norms: “affirmative precepts do not bind always, but for a fixed time (semper sed non ad semper)”; “negative precepts bind always and for all times (semper et ad semper).”45

AL’s failure to note that Aquinas is referring to affirmative moral norms leaves the impression that he means that all moral norms, including negative norms, are subject to failure under certain circumstances. This raises serious concerns, because that view contradicts the definitive Catholic teaching on the existence of intrinsically evil acts and the exceptionless norms that prohibit them.46 This teaching was reaffirmed as the central theme of St. John Paul II’s arguably most important encyclical, Veritatis splendor,47 which Amoris laetitia never references. The implications of contradicting this teaching can be plainly seen: if we dispense with exceptionless moral norms, we dispense with the exceptionless norm against adultery divinely revealed by the Sixth Precept of the Decalogue.

Tenth ambiguity: Does AL teach that individuals living more coniugale are free to receive the Eucharist? (AL 305)

This ambiguity has been addressed throughout our essay, but the controversial footnote 351, which has special relevance for that question, warrants specific attention. That footnote appears in no. 305 and is attached to the following sentence: “Because of forms of conditioning and mitigating factors, it is possible that in an objective situation of sin—which may not be subjectively culpable, or fully such—a person can be living in God’s grace, can love and can also grow in the life of grace and charity, while receiving the Church’s help to this end.351” Footnote 351 reads: “In certain cases, this [i.e., the Church’s assistance for people in ‘irregular’ relationships] can include the help of the sacraments.”

The reference in no. 305 to the possible lack of subjective culpability again raises the question of whether the text means that only those who lack sufficient reflection and/or deliberate consent may rightly receive Holy Communion. As we have seen, however, AL 303 explicitly states that these individuals “recognize that [their] given situation does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel” (emphasis added). Does footnote 351 mean, then, to include only those who, like addicts, are incapable of deliberate consent? Neither AL 305 nor footnote 351 explicitly answers that question, but given the “immense variety of concrete situations” (AL 300) of the people about whom AL is concerned, it seems that those passages mean to include people who are capable of consenting to live as brother and sister but are unwilling to do so. We find that conclusion disconcerting, because it seems clear that a person living more coniugale who receives Holy Communion does precisely what St. Paul warns against: he or she “eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner,” and so “eats and drinks judgment upon himself” (1 Cor 11:27, 29).

Conclusion

Let us summarize the manner of priestly accompaniment that AL8 envisages. A priest offers pastoral care to divorced and civilly remarried individuals who think that both separation and living together as brother and sister are inconsistent with the welfare of the children. The priest facilitates their understanding of their situation before God and so, among other things, enlightens their consciences about the disparity between their life-state and the teaching of the Gospel on marriage. He knows they struggle with fidelity to that teaching and believes their struggle may mitigate their culpability for violating the Gospel’s command. Conscious of their painful exclusion from the sacraments and of the importance of receiving sacramental grace, he helps them consider ways the exclusion can be surmounted. In the end, he supports their conclusion that living in their more coniugale relationship is the best they can give, as well as their belief that God also thinks so.

By omitting essential conditions for rightly receiving the sacraments, the Exhortation strongly suggests that these individuals are free to receive, and thus to be admitted, to Holy Communion even when they fail to meet those conditions. The text does not establish as a condition for receiving the sacraments that divorced and civilly remarried people cease living more coniugale. It does not specify that the partners must be incapable of deliberate consent. And it does not require that they secure writs of nullity testifying to the fact that their first marriage was invalid.

The reader seems to be invited to conclude that some people whose first unions broke down, perhaps under painful circumstances, but who as far as the Church is concerned are still validly married—people who are now living in sexually active second relationships, who understand that this is contrary to Sacred Scripture and Church teaching, and who though capable of changing their situations are unwilling to do so because they find it extremely difficult—may after a process of accompaniment rightly receive sacraments.

This conclusion poses serious doctrinal problems. How can it not entail a contradiction with at least one of the following revealed truths: (1) no one should receive the Eucharist without being willing to conform his or her life to the objective demands of the Gospel; (2) a consummated Christian marriage is absolutely indissoluble; (3) for a married person to have sex with someone other than his or her valid spouse is always adulterous; or (4) adultery is always gravely wrong?48

Let us consider these four revealed truths and our reasons for raising the disconcerting question of whether AL8 contradicts one or more of them.

The first revealed truth is that no one should receive the Eucharist without being willing to conform his or her life to the objective demands of the Gospel. AL insists that people living in more coniugale relationships may not be culpable.49 These repeated affirmations might lead one to claim that the Exhortation does not contradict the first truth; one might argue that although those living in more coniugale relationships do not in fact conform their lives to the objective demands of the Gospel, at least some such people can rightly receive the Eucharist because they are not unwilling to fulfill those demands, but rather are prevented by circumstances from doing so.

The problem with this argument is that AL fails to communicate the moral truth taught by the Church that the only conditions that could mitigate culpability for grave sin are either the agent’s own ignorance or incapacity. That is to say, only the lack of either sufficient reflection or deliberate consent could exculpate someone who does what is gravely wrong. In the case at hand, this means that individuals will be inculpable only if they either do not grasp their obligation to refrain from sexual relations or are incapable of avoiding the behavior—and such incapability would assume either that they compulsively engage in sex acts with their second partners or are victims of sexual assault.50

But AL gives the impression that those who lack sufficient reflection or deliberate consent are not the only divorced and remarried people who may rightly receive the Holy Eucharist. For despite its emphasis on inculpability, the Exhortation neither teaches nor even suggests that true inculpability—i.e., inculpability understood as the Church has always taught it—is a condition for receiving. This leaves the reader to conclude that true inculpability is not a condition. But if people who are culpable can rightly receive the Eucharist, then the willingness to conform one’s life to the objective demands of the Gospel is obviously not a condition for rightly receiving.

The second revealed truth is that a consummated Christian marriage is absolutely indissoluble. The Exhortation’s frequent affirmations of marital indissolubility51 suggest that reception of Holy Communion by these individuals would not compromise that truth. AL rightly affirms that validly married couples “who remain faithful to the teachings of the Gospel . . . bear witness, in a credible way, to the beauty of marriage as indissoluble.”52 However, the document also says that the Christian community’s care of “the divorced who have entered a new union . . . is not to be considered a weakening of its faith and testimony to the indissolubility of marriage; rather, such care is a particular expression of its charity.”53 In context, this latter statement is problematic. The Christian community’s care can bear witness to marital indissolubility and be charitable only if it supports marriage’s essential property of exclusivity, which married people are themselves morally obliged to respect. Those who are living more coniugale plainly fail to do so and therefore should not receive Holy Communion. For a pastor of souls nevertheless to approve their reception of Holy Communion implies that they have no such obligation, and that marriage is not indissoluble after all. Pastoral care that gives such an impression cannot be reasonably understood as charitable. In the end, AL8 does not teach or even suggest that these individuals’ original marriages must be invalid, or that their reception of the Eucharist conflicts in any way with the Church’s teaching on marital indissolubility. These omissions strongly suggest that in real-world cases, “indissolubility” does not necessarily exclude all expressions of sexual intimacy between the divorced and civilly remarried.

The third and fourth revealed truths are, respectively, that it is always adulterous for a married person to have sex with someone other than his or her valid spouse, and that adultery is always gravely wrong. We have already seen that Cardinal Kasper says he is unwilling to affirm that more coniugale relationships are necessarily adulterous.54 AL does not profess such an unwillingness, but rather avoids the issue entirely. In fact, except with reference to the woman caught in adultery,55 the term adultery appears nowhere in the entire Exhortation. Thus, AL avoids explicitly committing itself either to the view that more coniugale relationships are always adulterous or to the view that adultery is always wrong. One naturally wonders whether the reason for these omissions is that the issue of adultery poses an insuperable problem for the view that in some cases individuals living more coniugale—that is, individuals who are validly married to another person, who understand that their life-state conflicts with Sacred Scripture and Church teaching, and who, though capable of living as brother and sister, are unwilling to do so because they would find it extremely difficult—can rightly receive Holy Communion.

A further question

The problems considered above raise an important question: How should a Catholic receive a new teaching that seems to conflict with a previous more authoritative teaching?

Everyone who is resolved to be faithful to Catholic teaching must contend with the question of how to proceed if he or she suspects that a noninfallibly proposed papal or ecclesial teaching is contrary to a truth of the faith, or to a definitive teaching pertaining to the deposit of faith, or even to another teaching that is more authoritatively taught. We propose the following. When raising questions about the contents of such a teaching, one should begin with a presumption that it can be reconciled with Catholic doctrine, and therefore should undertake a process of careful examination to dispel one’s doubts. One should compare the teaching fairly with the more authoritative teachings.56 If after due diligence one is unable to reconcile it with a more authoritative teaching, then a faithful Catholic is warranted—indeed is obliged—to withhold assent unless and until it can be shown to be consistent with those sources.57 In such a case, one does not engage in the dissent that Donum veritatis condemns.58

The conclusions to which AL’s problematic passages point raise an important ecclesiological question about the nature and scope of magisterial teaching that has not as yet been adequately addressed by the Church or by theologians.59 What is proper subject matter for a teaching to be considered part of the magisterium of the pope or college of bishops? The question is important because every truly magisterial (authoritative) teaching, including moral teachings, is meant to bind the consciences of those to whom it is addressed. Indeed, moral teachings bind consciences not only to affirm those teachings as being true, but also to direct actions in accord with them.

Should everything promulgated by a pope or the college of bishops as magisterial be held indeed to be magisterial—that is, to be properly authoritative—by those to whom it is addressed?60 AL was promulgated as a post synodal apostolic exhortation, a document that, though relatively low in ecclesial authority, is considered part of the ordinary and universal magisterium of the papacy. When he was prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Joseph Ratzinger taught that ordinary and universal teachings “are set forth in order to arrive at a deeper understanding of revelation, or to recall the conformity of a teaching with the truths of faith, or lastly to warn against ideas incompatible with these truths or against dangerous opinions that can lead to error.”61

Ratzinger’s presumption is that ordinary and universal teachings of the magisterium are consistent with definitive magisterial teachings. If, however, a teaching in an apostolic exhortation or another ecclesial document is inconsistent with such teachings, then the new teaching is rightly taken to be untrue. And if it is not true, would we want to hold that it is magisterial? Yet it does seem problematic to deny that a magisterial teaching can be mistaken, since then all properly magisterial teachings would ipso facto be infallible. But if it should be considered magisterial, then it would seem to place the faithful who are aware of the teaching’s falsity in an untenable situation, bound to accept with “religious submission of will and intellect” (LG 25) a teaching that they are simultaneously obliged in conscience to reject. In light of the problems raised by the teaching of chapter eight of Amoris laetitia, it is essential that theologians take up and propose appropriate solutions to these questions.

Endnotes:

1 See Bishops of the Pastoral Region of Buenos Aires, “Basic Criteria for the Application of Chapter VIII of Amoris Laetitia” (Sept. 5, 2016); Bishops of Malta and Gozo, “Criteria for the Application of Chapter VIII of Amoris Laetitia” (Jan. 2017). Also see the interview of Cardinal Christoph Schönborn by Antonio Spadaro, S.J., “Cardinal Schönborn on ‘The Joy of Love’: The Full Conversation,” Brian McNeil, trans., America Magazine, August 9, 2016, Schönborn presented the text of Amoris laetitia during the official press conference on April 8, 2016, in the Holy See’s newsroom.

4 AL is generally concerned with priests admitting people to the Eucharist. The Exhortation does not seem to be using admit to refer to the duties of the minister of Holy Communion, which are set out in canons 912 and 915 of the Code of Canon Law and are not referenced in AL. The document’s overarching concern, rather, is with the duty of the priest to “accompany” people by explaining when the priest can approve of their reception of the Eucharist. We intend the same meaning in our use of admit. But, of course, pastors of souls should only approve the reception of the Eucharist by those who can rightly receive it. For that reason, we will usually use the language of receiving the Eucharist and consider who can rightly receive, and in that way indicate the responsibility of both the recipient and the pastor.

5 It seems clear that the statement of the Buenos Aires bishops, “when a declaration of nullity could not be obtained,” refers to couples who are in fact validly married. Matthew Levering also interprets the pope’s remarks about the Buenos Aires statement as referring to “divorced and remarried persons, bound by a prior sacramental marriage,” The Indissolubility of Marriage: Amoris Laetitia in Context (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2019), 93 (emphasis added). However, that statement could, though implausibly, refer only to the rare case of remarried divorcees who have certain knowledge that their first union was not a valid sacramental marriage but who are unable to show this in the external forum. Cardinal Müller, who thinks that interpretation unlikely, nevertheless considers the ambiguity serious enough as to warrant a clear answer to a dubium that asks whether sacramental absolution may sometimes be given to a validly married person who is unwilling to refrain from having sexual relations with a person with whom he or she lives in a second union. See E. Christian Brugger and Fr. Peter Ryan, SJ, “Cardinal Gerhard Müller exposes a crisis in Church teaching,” Catholic World Report, 9 December 2023. For Müller’s article, see “Open letter to Cardinal Dominik Duka,” Settimo Cielo, October 13, 2023. The same ambiguity is repeated in the DDF text published on Sept. 25, 2023, responding to Dubia 6 (of ten) submitted in July 2023 by Czech Cardinal Dominik Duka regarding the teaching of AL on this same question. The dubium asks whether cases of divorce and civil remarriage should be “dealt with by the competent ecclesiastical tribunal.” The DDF replies: “The problem arises in more complex situations where a Declaration of Nullity cannot be obtained. In these cases, it might be possible to undertake a pathway of discernment that stimulates or renews the personal encounter with Jesus Christ, also in the sacraments.”

6 AL’s ambiguous language would seem to leave open the question of whether the text means to permit reception of the Eucharist by individuals who are willing but unable to change their behavior, or who are just unwilling because of the difficulties involved in doing so. This ambiguity is repeated in the DDF response to Cardinal Duka’s third dubium: “Francis maintains the proposal of full continence for the divorced and remarried in a new union but admits that there may be difficulties in practice. Therefore, he allows, in some cases, after adequate discernment, the administration of the sacrament of Reconciliation even when one fails to be faithful to the continence proposed by the Church” (original emphasis). This, too, leaves open the question of whether such cases include those who are unwilling to commit themselves to live in continence, or are limited to situations in which one has confessed one’s sin and firmly resolves to sin no more, but being aware of past failure and one’s own weakness, fears falling again. As John Paul II puts it, “this does not compromise the authenticity of the intention, when that fear is joined to the will, supported by prayer, of doing what is possible to avoid sin.” (John Paul II, Letter to Cardinal William W. Baum on the occasion of the Course on the Internal Forum organized by the Apostolic Penitentiary [22 March 1996], 5: Insegnamenti XIX/1 [1996], 589; see also Amoris laetitia, footnote 364).

7 See, for example, the forward to five dubia submitted by four cardinals to Pope Francis on “contrasting interpretations of Chapter 8 of Amoris Laetitia”; the cardinals write: “We want to help the Pope to prevent divisions and conflicts in the Church, asking him to dispel all ambiguity,” quoted from “Full Text and Explanatory Notes of Cardinals’ Questions on ‘Amoris Laetitia,’” National Catholic Register, Nov. 14, 2016. See also Irish theologian, Vincent Twomey, who refers to AL chapter 8 as “an ambiguous chapter of a hotly contested post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation” (emphasis in text), in “The refined, problematic casuistry of Abp. Fernández’s defense of chapter 8 of “Amoris Laetitia,” Catholic World Report (July 6, 2023).

8 Canon law refers to a consummated sacramental marriage as ratum et consummatum, which it defines as a valid marriage between baptized Christians who have “performed between themselves in a human fashion a conjugal act which is suitable in itself for the procreation of offspring.” Can. 1061.1.

9 If a marriage is not ratum et consummatum, it can be dissolved by the Church, but unless the marriage has actually been dissolved, it remains valid.

10 See AL 52, 53, 62, 77, 86, 123, 124, 178, and 243. We will consider below whether the implicit teaching of AL comports with those affirmations.

11 See Levering, “The Church as Temple of the Spirit: Is there Room for Magisterial Error?,” Communio 50 (Spring 2023), 7–36 at 29.

14 “If these people were admitted to the Eucharist, the faithful would be led into error and confusion regarding the Church’s teaching about the indissolubility of marriage” (FC 84).

15 German Cardinal Walter Kasper, sometimes referred to as “the pope’s theologian”, defended admitting this cohort to Holy Communion in an address that Pope Francis invited him to give to the College of Cardinals in February 2014 (published as The Gospel of the Family [New York: Paulist Press, 2014], p. 32). In thanking him the following day, the pope extolled Kasper’s book on mercy as “deep theology, and serene thoughts in theology”. Kasper says: “The question that confronts us is this: Is this path beyond rigorism and laxity, the path of conversion, which issues forth in the sacrament of mercy—the sacrament of penance—also the path that we can follow in this matter? Certainly not in every case. But if (1) a divorced and remarried person is truly sorry that he or she failed in the first marriage, if (2) the commitments from the first marriage are clarified and a return is definitively out of the question, if (3) he or she cannot undo the commitments that were assumed in the second civil marriage without new guilt, if (4) he or she strives to the best of his or her abilities to live out the second civil marriage on the basis of faith and to raise their children in the faith, if (5) he or she longs for the sacraments as a source of strength in his or her situation, do we then have to refuse or can we refuse him or her the sacrament of penance and communion, after a period of reorientation? … Is it not necessary precisely here to prevent something worse? For (6) when children in the families of the divorced and remarried never see their parents go to the sacraments, then they too normally will not find their way to confession and communion. (7) Do we then accept as a consequence that we will also lose the next generation and perhaps the generation after that? Does not our well-preserved praxis then become counterproductive?” (Numbering added.) Kasper’s comments are problematic on multiple levels: (1) while sorrow is obviously to be commended, whether or not a spouse is sorry has no bearing on whether the bond of his or her marriage perdures; and if it does—and we can be certain that it does if a Christian marriage is valid—then sexual relations outside that bond are by definition adulterous; (2) a proper clarification of the commitments from the first marriage will make clear the necessity of avoiding adultery; (3) although the spouse should remain true to any new commitments that are morally binding, he or she should also be guided by the Council of Trent’s teaching (see note 36 below) that it is always possible to undo a morally wrong commitment without new guilt; (4) striving to live the second civil marriage on the basis of faith entails having the faith that God will give one the strength to avoid adultery; (5) the spouse should not expect to find strength in sacraments that he or she is not properly disposed to receive; (6) it is not the failure of the parents to receive the sacraments while living in an adulterous relationship, but their unwillingness to abstain from adultery so they can properly receive that prevents them from giving their children a salutary example of receiving the sacraments; (7) the possible loss of faith in the next generation cannot be attributed to their parents’ unwillingness to commit adultery; rather, a proper concern for handing on the faith includes avoiding giving the bad example of adultery. Kasper is doubtful as to whether such sexual relations are in fact adulterous: “I can’t say whether it’s ongoing adultery”; nevertheless, Kasper still thinks “absolution is possible,” even if the individuals do not resolve to live as brother and sister, since such a resolution, he says, would be “a heroic act,” and “heroism is not for the average Christian.” But while it may be that many average Christians never face the daunting choice between committing a mortal sin and exercising heroic virtue, some plainly do (see note 37 below). Moreover, as Lumen gentium 11 teaches, “all the faithful, whatever their condition or state, are called by the Lord, each in his own way, to that perfect holiness whereby the Father Himself is perfect.” And attaining perfect holiness may very well require heroism. So, even if in some instances forgoing adultery requires heroic virtue, one cannot conclude on that basis that such heroism is not required of average Christians. Kasper’s comments are in Matthew Boudway and Grant Gallicho, “An Interview with Cardinal Walter Kasper: Merciful God, Merciful Church,” Commonweal.

16 To call the relationship of such individuals adulterous sometimes raises objections. The pope’s biographer, Austen Ivereigh, for example, says: “You cannot say that everyone who is divorced or remarried is an adulterer. Adultery is a moral category. A woman who is abandoned by her husband and remarries for the sake of her children—say, 15 years later—is she an adulteress? Is that an appropriate description?” Ivereigh’s emotionally charged example reveals his own doubt that sexual activity outside of valid marriage is always wrongful. The question, however, is an objective one: Is her first marriage still valid? If yes, then although we should of course treat her with compassion, we must acknowledge that because marriage is indissoluble, her choice to have sex with someone she knows is not her true husband is a choice to commit adultery. Ivereigh’s example is found in James Macintyre, “Has the Pope gone soft on adultery? The Catholic Church’s civil war,” Christianity Today, Sept. 27, 2017.

17 The “great difficulty” argument is found again in the writings of the new prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF), Víctor Manuel Fernández, widely assumed to be the principal author of AL. Defending AL chapter 8, Fernández argues that the difficulty a divorced and civilly remarried woman would experience in separating from her civil marriage partner can mitigate her responsibility for remaining in the objectively adulterous relationship. José Granados criticizes this, saying that inculpability “cannot be due simply to the difficult situation in which the person finds himself, but to the deprivation of knowledge and/or freedom.” He explains: “Fernández seems to include among these factors that mitigate responsibility also circumstances external to the person… Here we are already moving from excusing a person for lack of subjective disposition to excusing him for the circumstances in which he lives.” Granados, “‘Charity Builds Up’ (1 Cor 8:1)—But Which Charity? On Víctor Manuel Fernández’s Theological Proposal,” Communio 50 (Winter 2023), p. 10, referring to Fernández, “El capítulo VIII de Amoris Laetitia. Lo que queda después de la tormenta,” Medellín 43 (2017), 455. Perhaps Fernández means that external circumstances can influence a person’s subjective disposition, but he never makes that clear. But even if he does have this in mind, it would not exculpate the person unless Fernández means that the person is either unaware that grave matter is at stake, or incapable of making a free choice with respect to it, or both.