After World War II, the Franco-Swiss architect who went by the name of Le Corbusier erected brazenly expressionistic buildings, including an 18-floor Marseilles housing project and a hilltop pilgrimage chapel outside the little French town of Ronchamp, that changed the course of modernist architecture. The exposed, poured-in-place “raw” concrete—béton brut—of which they were wholly or partially constructed accounts for “brutalism,” the name by which the architectural craze these buildings launched soon came to be known. The term got traction thanks in no small part to the mode’s tendency to aesthetic brutality. It amounted to a viral reaction against the tidy reductionism of modernism’s own glass-walled box.

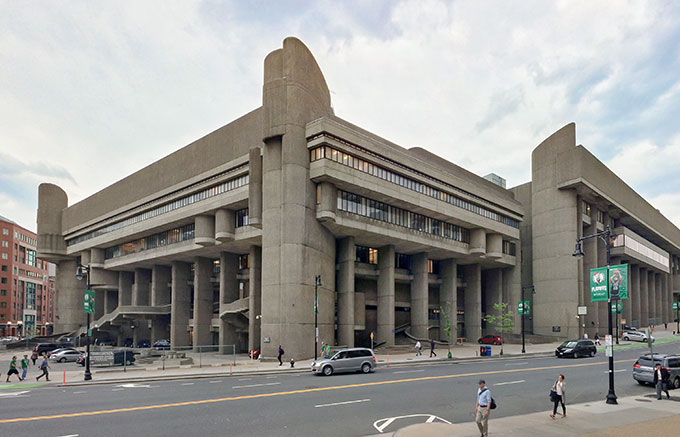

In the United States, brutalism had its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s. It was never popular. The “crowdsolving” design platform Buildworld recently ranked two infamous specimens, the J. Edgar Hoover FBI headquarters building in Washington and Boston’s City Hall, as America’s two ugliest buildings. Brutalism has nevertheless regained prestige among the culturati in Britain and the U.S. Hence this memorable 2021 Washington Post headline: “Brutalist buildings aren’t unlovable. You’re looking at them wrong.” In fact, an expanding body of scientific research indicates we’re looking at them right. With their valuable study, Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment (2021), architect Ann Sussman and urban planning professor Justin B. Hollander allow us to see that brutalist structures are loathed because they are devoid of qualities humans are hardwired to seek in their architectural surroundings.

Humans being the wayward creatures we are, however, our deeply ingrained sensory responses to built form can be overridden or suppressed by influencers du jour or academic indoctrination. Politicized peer pressure can come into play as preference for traditional—especially classical—architecture is falsely interpreted as an automatic indicator of a conservative, reactionary, or even racist mindset. And where the visual arts are concerned, it has long been fashionable to embrace high-concept dysfunction as being cool or progressive or somehow redolent of authenticity. So it should come as no surprise that 15 or so years ago, The Standard, a boutique hotel echoing the Marseilles edifice and other Corbusian housing asylums perched on concrete stilts, was erected athwart the popular High Line elevated park on Manhattan’s Far West Side. A remarkable 2015 conspectus assembled by three academics, Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston, even advocates replacing the thoroughly appropriate “brutalist” monicker with “heroic.”

Many of America’s brutalist buildings now present a choice between expensive renovation and demolition. The FBI has long been eager to vacate its Hoover headquarters, which dates to 1975. Fronting on Pennsylvania Avenue between the Treasury and the Capitol, the 2.8-million-square-foot behemoth rises eight stories along the avenue, and 11 stories to the rear, where it boasts an unsightly cantilevered superstructure. Nearly everyone, starting with President Trump, realizes the building has got to go.

But preservationists will try to save two of Washington’s brutalist structures that also face possible demolition, depending on the course of future redevelopment in the city’s Southwest quadrant, where they are located: the headquarters of the Departments of Health and Human Services and Housing and Urban Development. Both were designed by top-drawer modernist Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), and both will likely be sold by Trump’s General Services Administration in a major federal real estate downsizing campaign. Breuer’s HHS lies near the foot of Capitol Hill. It’s a massive, visually abrasive concrete hulk, suspended from trusses over a recessed lobby. The HUD building, shaped like a dog-bone in plan and raised on stocky pairs of supports resembling pigs’ legs—a variation on the stilts, or pilotis, employed by Le Corbusier—is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Historic preservation became a national cause thanks to the destruction of Manhattan’s majestic Pennsylvania Station during the 1960s. Its popularity arose from the public’s desire to protect handsome older buildings from demolition and replacement by ugly ones. Modernist preservation activists and review board members have largely undermined this original intent. Boston’s City Hall, which resembles an upside-down ziggurat with large cavities and cantilevered volumes on its lower levels and broad upper floors perched on titanic concrete planks, is now an official Boston Landmark. It is the centerpiece of the dystopian 60-acre Government Center urban renewal precinct designed by I. M. Pei to replace dilapidated historic fabric on and around the city’s old Scollay Square. Pei’s Dallas City Hall, another widely reviled brutalist exemplar whose steeply-pitched, seven-story, 560-foot-long main elevation again suggests an inverted ziggurat or pyramid, also appears to be on track for landmark status.

Brutalism’s renewed cachet is reflected in two current museum exhibitions and even an award-winning movie, The Brutalist. I recently ruined my afternoon by seeing the latter, a very, very long (three hours and 35 minutes, including a 15-minute intermission) production whose protagonist is a Bauhaus-trained Hungarian Jew and Holocaust survivor who emigrates to America after the war to practice architecture. In the opening scene we see the Statue of Liberty upside down, then sideways, and things don’t get much better from there. Though he has been a successful architect in Hungary, our hero, László Tóth—played by Adrien Brody, who has now won an Oscar for his performance—is reduced for a time to living in a Philadelphia homeless shelter and shoveling coal. As befits a martyr to the cause of Art, he is a heroin addict. Even in his architectural practice, he must endure the violent mood shifts of a blue-blooded patron who commissions him to design—as a memorial to his mother—what proves to be a rather odd, if not brutalist, concrete community center situated on a Bucks County hilltop. (The hilltop is actually in Hungary, where the movie was mostly filmed, and the reduced-scale model used as a stand-in for the completed community center, though it includes a chapel, was conceived by the movie’s production designer with death-camp crematoria in mind.) Breuer, a Hungarian Jew and prominent Bauhaus alumnus, served as inspiration for the Tóth character, though he came to this country before the war and was surely not a junkie. It has not gone unnoticed that The Brutalist’s plot is extremely farfetched. Tóth would have been much more likely to land work in a modernist office the moment he arrived on our shores, followed by a plum teaching post.

As for the exhibitions, Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph is on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum Fifth Avenue through March 16. It features the meticulous architectural drawings of a second-generation modernist luminary whose wide-ranging career never fully recovered after his brutalist work, including the building he designed for Yale’s architecture school, fell out of favor in the late 1960s. Though it gives Rudolph (1918–1997) more credit than he deserves, Materialized Space and Met curator Abraham Thomas’s accompanying catalog shed considerable light on Rudolph’s strange aesthetic sensibility. Meanwhile, the National Building Museum in Washington is offering Capital Brutalism: A Survey of Past, Present and Future Brutalist Architecture in the Nation’s Capital through June 30. It features architectural photographer Ty Cole’s extraction of putatively engaging images from bad buildings—photography’s long-established role in the modernist PR routine.

Capital Brutalism focuses on eight structures. Breuer’s HHS and HUD buildings rank among them, as does the FBI building. Also figuring in the exhibit is the Energy Department’s James Forrestal building, six blocks west of HHS on Independence Avenue. Perhaps the exhibit’s most immediately endangered building, Forrestal’s boxy northern structure with its monotonous window grid (a feature shared with Breuer’s HUD) will be a familiar sight to many who have visited the Smithsonian Institution’s Castle. It is raised over 10th Street on polygonal concrete shafts and faces the Castle from across the avenue. Then comes Gordon Bunshaft’s concrete donut-bunker, the Hirshhorn Museum, with its narrow, gun-emplacement-like opening facing the National Mall. Georgetown University’s Lauinger Library—which features two hollow tower-like structures that are readily visible from across the Potomac—is less bad because it’s a more complex and arguably better resolved composition than the other brutals. Aside from the towers, decorative accents include concrete planks arrayed like attic finials. The library is the work of John Carl Warnecke, who designed JFK’s Arlington Cemetery gravesite. Alas, “Lau” and its brownish concrete are widely unloved. “When it comes up on tours, I just admit it’s an ugly building,” an undergraduate tour guide told the campus newspaper a decade ago.

Capital Brutalism misleadingly features two non-brutalist structures, presumably to make the mode seem less brutal. Harry Weese’s stations for Washington’s Metro subway system are vaulted spaces with coffer-like rectangular recesses meant to harmonize with Washington’s classical architecture. Not exactly what you’d expect of a brutalist project. That the vaults consist of exposed concrete doesn’t make the stations brutalist. With their astutely subdued lighting and their platform pavements’ agreeably ruddy hexagonal tiles, they rank among modernism’s most impressive American achievements.

An office building of brick, glass, and concrete on Dupont Circle that was designed to fit into its historic context, the Euram Building, is also misleadingly featured. Designed by Washington’s Hartman-Cox Architects, the Euram is a thoughtful exercise in high-modernist formalism that, while not as satisfying as the firm’s later, classical Market Square duo (1990) on Pennsylvania Avenue, is urbanistically polite, something brutalist buildings seldom are. As part of the exhibit, architects were commissioned to envision more or less drastic, more or less preposterous reconfigurations that would spare the six truly brutalist structures it features total destruction. The Metro stations and the Euram don’t get this treatment. The drastic reworking of the Hoover envisioned by a team from a corporate firm, Gensler, manages to make it even uglier by breaking the building up into a cacophony of multipurpose fragments and supersizing its cantilevered attic.

President Trump has a different idea. During his electoral campaign, he said he intended to replace the building with a new FBI headquarters, so the agency would continue to be located near the Department of Justice building in the nearby Federal Triangle. Given the president’s stated policy of restoring the classical tradition in Washington’s federal architecture, that could prove a colossal undertaking of significant cultural import. Demolishing the vast concrete pile would be expensive, while erecting a worthy classical replacement on this scale would require enlightened government patronage and architects and planners of outstanding ability. Time will tell whether Trump sticks to his campaign promise.

Capital Brutalism acknowledges that Breuer’s HUD was erected as part of an enormous urban renewal project that, in transforming Washington’s Southwest quadrant, displaced over 23,000 people and eliminated 1,500 businesses. It’s ironic that the structure was eventually named in honor of Robert C. Weaver, the first HUD secretary and the first black Cabinet member (under Lyndon B. Johnson), considering three-quarters of those who lost their homes during the redevelopment juggernaut were blacks living on shabby old rowhouse blocks that, like Boston’s Scollay Square neighborhood, should have been much less destructively rehabilitated. The exhibition curators, photographer Cole and University of Oklahoma architecture professor Angela Person, might also have acknowledged Breuer’s failure in place-making with the HUD project. The spatial desolation of the plaza in front of the building was so acute, and so resented by HUD employees, that during the 1990s a postmodern landscape designer attempted to liven it up with round concrete planters doubling as benches and plastic life-saver-shaped canopies erected on 14-foot steel poles.

During the war, Paul Rudolph (1918–1997), an Elkton, Kentucky, native who was considered a particularly brilliant student at Harvard’s modernist Graduate School of Design, supervised ship repair at the Navy Yard in Brooklyn, where he was smitten with the beauty of destroyers. Later on, the call for a “new monumentality” and Le Corbusier’s towering influence led him to erect brutalist buildings in concrete textured with vertical “corduroy” striations. These include Rudolph’s hideous Boston Government Service Center, a major component of Pei’s Government Center precinct. Evidently intended to lend monumental expression to the brutal force of heavy industry, this sculpturesque, phenomenally disjointed agglomeration consists of two connected buildings—one of which houses a mental health center, of all things. The complex has not aged gracefully. Yet the state, at last report, intends to renovate it with a view to addressing a housing shortage. Materialized Space includes an elevation drawing of one of the service center’s frontages, but it doesn’t come close to showing how repellent the complex is. Even so, it will probably be landmarked in due course. Rudolph devotees are determined to avoid a repeat of the 2021 demolition of one of the architect’s most important brutalist works, the Burroughs Welcome headquarters in North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park.

The exterior of Rudolph’s Art and Architecture Building at Yale, erected while he was dean of Yale’s architecture school, makes a considerably more unified impression than the Boston service center, but it generated intense controversy even so. An assiduous networker whose creations generated one media photo spread after another, Rudolph won the Yale appointment before turning 40. His Art and Architecture building occupies a high-profile street-corner site. It offers no curves, just rectilinear masses and voids whose picturesque intricacy is essentially decorative. Inside, Rudolph managed to stash 37 disjointed levels into seven stories. Completed in 1963, the building was seriously damaged in a 1969 arson attack believed to have involved students. Rudolph had left Yale by then, and he soon became unfashionable. It might surprise us today that he was branded an establishment architect, part of the technocratic elite that had gotten the nation stuck in the Vietnam quagmire.

In addition to the Art and Architecture Building, carefully restored in 2008 in accordance with Rudolph’s design, the architect left New Haven with a two-block-long, six-floor brutalist parking garage whose paired piers form multilevel mutant arches, as if this were modernity’s answer to the Roman aqueduct. New Haven is also home to his Crawford Manor apartment building for the elderly. It has the same unwelcoming industrial vibe as the Boston Service Center, with less discombobulated massing. It is listed on the National Register. But a visit to New Haven serves as a useful reminder that the havoc wrought by movers and shakers like Rudolph is hardly limited to their own creations. If you take a taxi to the train station from the Yale campus, you might pass by the Blessed Michael McGivney Pilgrimage Center (a Knights of Columbus museum now named after the order’s founder) and the New Haven police headquarters. Both buildings were designed by a local office, both feature Rudolph-style textured concrete—and both are abject brutalist eyesores.

Materialized Space—normal people might wonder what that phrase is supposed to mean—cannot and does not ignore Rudolph’s obsession with drastically over-scaled and dehumanized megastructures. The obsession is epitomized by an unrealized, Ford Foundation-commissioned Lower Manhattan Expressway urban renewal scheme (1967) for a serpentine mixed-use monster including glass towers, parking decks, and monorails that would have ploughed its insanely destructive course from the Lincoln Tunnel through SoHo. The monster’s forked tail would have led from the Lower East Side to the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges. Rudolph was manifestly prone to delirious notions of the automobile’s ramifications for urban design. His 726-foot-long, federally funded concrete parking garage in New Haven is one-third its originally intended length, having been conceived at the outset as part of an unrealized urban renewal megaproject.

Neither of these exhibits provides an adequate idea of the impact Le Corbusier’s seminal brutalist buildings had on the modernist mindset. The chapel at Ronchamp, with its half-a-loaf towers and voluminous roof that flares up into what might suggest the corner of a tricorn hat, is well known as a pilgrimage site—for architects. Leaving aside Corbusian derivatives like The Standard hotel, many a latter-day architect working in a deconstructionist or other late-modernist mode has likely been inspired by the chapel’s esthetically nonsensical, eye-poppingly photogenic je ne sais quoi—and sought to match it with idiosyncratic creations of his or her own. One might be forgiven for thinking the misshapen, 225-foot-tall granite-clad totem designed to house the museum at the Obama Presidential Center, now under construction in Chicago’s Jackson Park, reflects such an aspiration.

In his foreword to the Capital Brutalism catalog, architecture critic and educator Aaron Betsky contends that Washington’s brutalist buildings “managed to make the case for a heroic”—that word again—“vision of shared institutions in a manner that was compelling and grand. It was exactly that success, however, that also made brutalism the target of criticism that veered off into political hatred.” (You’d think he was speaking of the Yale architecture building.) This reaction was the more unfortunate, Betsky informs us, given that brutalist architects were offering an alternative to “historical styles” that “reified an older, more elitist and hierarchical ideal.” The U.S. Capitol, in other words, is about elitism and hierarchy, while brutalism “showed both the resolution of democracy and its abstraction into institutions in clear forms.” Sure.

Betsky offers the kind of politicized, elitist academic sophistry we can expect should the decision be taken to demolish Breuer’s HHS and HUD buildings. The Brutalist’s director has gone so far as to equate hostility to brutalist buildings with hostility to immigrants. We’ll also hear about the virtues of conserving brutalist structures lest their embodied CO2 escape into the atmosphere, an event whose impact on climate change—a global, rather than local, phenomenon, lest we forget—would be less than minuscule. And we’ll hear reiterations of the Capital Brutalism catalog’s bromide that “[t]hough polarizing, brutalist buildings reflect an important period of our urban and architectural legacy.”

Make that “a disastrous period.” We should not hesitate to correct its gigantic errors.

Top Photo: The James Forrestal Department of Energy Building (1969), Curtis and Davis, architects (Photo: Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs)